New supermarket CEO’s making very old mistakes

With two supermarket CEO’s facing off against the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) in the battle for supermarket reputations, I wonder whether we will see vastly different behaviours from the new heads of Coles (ASX:COL) and Woolworths (ASX:WOW) than what we might typically have expected from their predecessors.

Already, it looks like the same traits of pride, greed, and short-sightedness are on display.

At issue is the common supermarket practice of raising prices dramatically, keeping them at the new elevated level for about a month, then dropping them slightly and promoting the latest ‘lower’ price as giving consumers a saving, a ‘helping hand’ if you will.

Indeed, their canned media releases in response to the news of the ACCC’s legal action still trot out the old chestnut of helping Aussies make ends meet.

However, the supermarkets’ reputations are at stake, and their chiefs’ beliefs about how best to defend them will be on display.

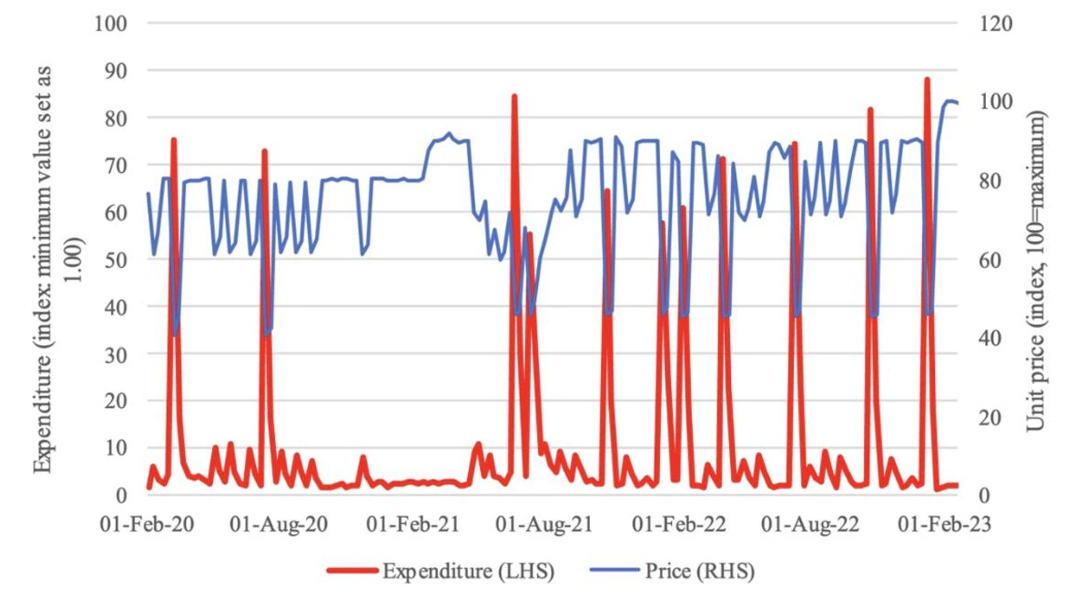

Discounts such as Coles’ “DOWN DOWN” promotions impact consumer behaviour and spending. Figure 1., reveals big spikes in buying a particular brand of olive oil when it is ‘on sale’.

Figure 1. Price drops lead to big spikes in spending

Source: X, @jasemurphy

Source: X, @jasemurphy

Because there is a genuine consumer response to the promotions, the claims a product is cheaper need to be genuine.

The case will likely hinge on whether a four-week period is long enough for a product to have been sold at the higher price point before a subsequent (albeit small) discount can be truly considered a promotable price drop.

Let’s call the price a product has long sold for ‘price 1’. We’ll call the egregiously high price ‘price 2’. Finally, we’ll call the price discounted from the egregiously high price ‘price 3’. Price 3 is consistently higher than price 1.

The ACCC will seek to demonstrate that because price 3 is higher than price 1, price 3 is not a discounted price at all. Presumably, they will have evidence that the supermarkets only ever intended to raise the price of said product from price 1 to price 3, and that the process of introducing both price 2 and the subsequent discount, is merely a tactic to make the price rise (from price 1 to price 3) palatable, while also providing the benefit of tricking consumers into thinking there’s a saving to be had. Win win!

The fact that supermarkets engage in this practice is not up for debate. They do, and that’s already been demonstrated in the public domain. The supermarkets will instead argue that keeping a product at price 2 for four weeks is a complying amount of time and no laws or codes have been broken.

So, the real question for supermarkets is whether they think defending such a practice, whether legal or not, is consistent with doing right by their customers or whether they take those customers for idiots and fools. The supermarkets’ reputation – and by extension, the long-term brand value, which is owned by the shareholders – hinges on the CEO’s responses to these existential questions.

What I am really interested in is how the new supermarket chiefs will approach the challenge of maintaining or even enhancing their reputations and whether they will act any differently from the way their predecessors might have.

One option is to deny, deny, deny. Go to court and defend the supermarket’s right to act as they have been caught acting because ‘it is what the law or code allows”.

That’s short-term thinking. Even if they win the argument, they lose what matters most – their standing in the community. Their reputation is already damaged, and any defence of current practices merely reinforces the community’s perception that behind the happy-clappy facade is a corporate culture that is rotten to the core.

Another option they’ll be spit-balling is to fight, and irrespective of whether they win or lose, believe it will all eventually blow over. And they are right; it will ultimately blow over because the world will move on. This approach considers the long term but dismisses the materiality of any adverse impact. Unfortunately, such an approach fails to consider the opportunity the current situation offers to enhance their reputations.

On March 24, 1989, the oil tanker Exxon Valdez hit a reef and spilled 11 million gallons (250,000 barrels) of oil into Alaska’s Prince William Sound. The company and its interests were damaged for much longer than shareholders might have otherwise had to endure because Exxon Corp. violated the cardinal rules of crisis management.

The hundreds of millions of dollars that Exxon Corp. spent cleaning up the colossal oil spill and settling related lawsuits and class actions had little impact on the financials of the oil giant. In 1988, its revenues were US$88.6 billion last year; today, they are US$344.5 billion. The real damage from the spill impacted Exxon in more intangible ways, including its reputation, delays to approvals and the increased challenges faced by the industry in trying to win permission for further oil drilling in the Arctic and offshore. Indeed, some of the lawsuits themselves could have been avoided had better crisis management been employed.

Exxon’s mistakes in its crisis management are now lore throughout marketing and brand courses at business schools worldwide. What all agree on is that Exxon’s biggest mistake was its then chairman, Lawrence G. Rawl, did not go to the site of the spill himself and take control in any visible way. This told the world the crisis was unimportant to management and spoke of a rotten culture.

The other big mistake is that the company’s public statements often contradicted the information being reported by those on the ground. This is simply lying.

People want to do business with people they like and trust.

If Australia’s supermarket CEOs defend their practices, as it seems they are already leaning towards doing, they will label themselves as people shoppers can’t like or trust.

The alternative is for the CEO to call a press conference, take personal responsibility for the required changes, apologise for the past, promise to change, and move on with the support of the community and the media firmly behind them.

The CEO and supermarket that does this first will win market share and keep winning it for a very long time.

The Montgomery Fund and the Montgomery [Private] Fund owns shares in Woolworths. This article was prepared 25 September 2024 with the information we have today, and our view may change. It does not constitute formal advice or professional investment advice. If you wish to trade Woolworths, you should seek financial advice.

Hi Roger,

I saw an expanded version of this article in the AFR on the weekend, so it’s that version that I’m referring to here.

I’m not sure as to the validity of one of the angle’s that you were taking in the AFR article (women CEO’s of both supermarket retailers being more sympathetic to the plight of their female shoppers (who make the bulk of the purchasing decisions in a supermarket setting) – these are highly profitable businesses and their shareholders expect them to remain so. I’d like to conjecture that both of these CEO’s haven’t got to where they are in their respective supermarket corporate hierarchies by being sympathetic to the plight of their customers – female or male. The supermarket retailers marketing machines would like everyone to think so, but that’s marketing for you.

In my view it’s a mistake for investors to focus solely on the “above the line” aspects of the supermarket/supplier trading relationship, it’s the “below the line” setting where the fun really starts. “Promotional rebate” deductions from supplier invoices, advertising campaign “contributions”, supermarket range reviews (an important way for suppliers to launch new products or add to an existing product range), postponed with little explanation, forcing suppliers to cancel or shift planned production (with resultant cost and trading reputation impacts), the intimidatory “transparent cost sharing” enquiry from supermarkets (those suppliers who provide too detailed cost information soon find their products being substituted with supermarket “home brand” offerings and finally, measuring supplier performance via “delivered in full and on time (DIFOT) metrics”, whilst supermarket Distribution Centre’s are choked with traffic congestion, delivery and union work practice delays and cumbersome and time consuming IT processes.

Hopefully the ACCC review dives into these ‘below the line” aspects of the supermarket/supplier relationship and suppliers themselves are forthcoming with detailed information to the ACCC.

In a global and like for like basis, these two supermarket retailers are some of the most profitable supermarket retailers in the world with one of the smallest supermarket customer populations to serve.

Something tells me that this ain’t an efficient market in operation.

Brilliant stuff Michael. Thank you for sharing!