Hubris?

Proverbs 18:16 warns “Pride goes before destruction, a haughty spirit before a fall.” The verse is the source of the modern cliché and despite its notoriety many are indeed trapped.

Whether hubris exists or existed at Pershing Square, a NY hedge fund, prior to 2015, we might never know but the returns last year of negative 20 per cent come hot on the heels of a vociferous and magniloquent billion-dollar attack on Herbalife.

Pershing Square’s founder Bill Ackman called the nutritional supplements company a “pyramid scheme,” likening its practices to those of the mafia and the Nazis.

The battle became personal and has involved lawyers, F.B.I. agents, Securities and Exchange Commission investigators and federal prosecutors as well as Democratic operatives, public relations firms, Justice Department investigators and the Federal Trade Commission. It hardly seems like activities associated with funds management and takes activism to a new level (whether that level is a new high or a new low, we leave for you to decide).

Perhsing has released its annual letter which can be found here.

The letter begins with the question “What happened?” and the subsequent answers however provide all investors with a salient reminder to remain humble and open to alternate views.

We quote from Pershing Square Capital Management’s January 2016 letter;

“2015 is a year we will not forget. There was no financial crisis except perhaps in the energy, commodity, and currency markets.1 There were no major new wars except for the rise of ISIS and growing global terrorism. The global economy has shown signs of weakness, most notably in China, but U.S. core growth appears sound. The substantial majority of our portfolio companies made continued business progress despite currency headwinds and a weakening global economic environment. Yet, the Pershing Square funds suffered their greatest peak-to-trough decline and worst annual performance ever. What happened?”

“Principally, we missed the opportunity to trim or sell outright certain positions that approached our estimate of intrinsic value. Our biggest valuation error was assigning too much value to the so-called “platform value” in certain of our holdings. We believe that “platform value” is real, but, as we have been painfully reminded, it is a much more ephemeral form of value than pharmaceutical products, operating businesses, real estate, or other assets as it depends on access to low-cost capital, uniquely talented members of management, and the pricing environment for transactions.”

“In retrospect, in light of Valeant’s leverage and the regulatory and political sensitivity of its underlying business, we should have avoided becoming restricted to preserve trading flexibility, or alternatively, we should have made a smaller initial investment in the company.”

Pershing Square acquired over 10 per cent of Allergan’s stock in March 2014. In April of the same year Valeant and Pershing Square announced a joint hostile bid for Allergan, which caused the shares in Allergan to rise 15 per cent and giving Pershing a billion dollar profit. But political attention on drug pricing and regulatory scrutiny, neither of which should be seen as unusual in an election cycle, as well as the termination of a distribution arrangement representing about seven per cent, produced a nearly 70 per cent decline in the stock.

It is this that probably prompted Ackman to write; “While not quite a lesson learned, as this has been a principle we have always believed, 2015 was also an important reminder that stocks can trade at any price in the short term.”

Importantly, and as is discussed in Valua.able, such is the temptation to overpay, organic growth should be preferred over acquisitions. Valeant’s business model however is to a large extent predicated on acquisitions. Valeant has acquired more than 108 businesses in the last eight years.

The letter continues; “We made… [an] error in not trimming our Canadian Pacific position when it reached ~C$240 per share. While we still believed CP was trading at a discount to intrinsic value at that price and there was the potential for CP to complete an industry-transforming, value-creating merger, in light of the size of the position as a percentage of the portfolio, and concerns we had about the Chinese economy, it would have been prudent to sell a portion of our investment.

“Our most glaring, albeit small, unforced error was buying additional stock in Platform Specialty Products at $25 per share to assist the company in financing an acquisition. We paid too much as we assumed the new transaction would create substantial value, and because we assigned too much platform value to the company. Our assessment was incorrect as execution difficulties, operating issues, currency effects, and financing issues have destroyed rather than created value.”

Ackman’s letter is a useful reminder to invest with humility.

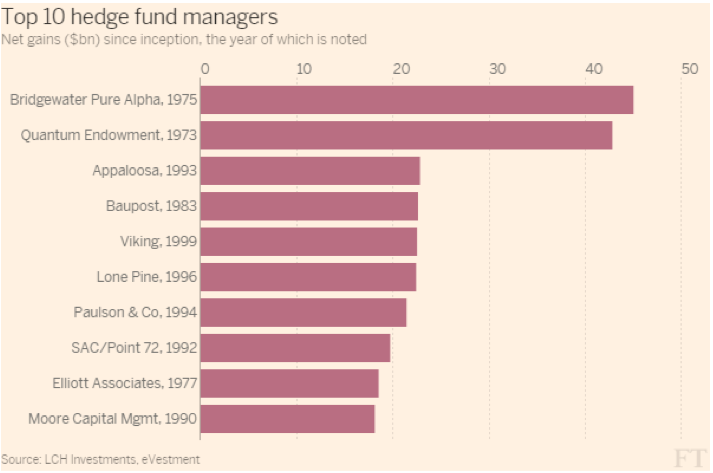

Not all hedge fund managers posted poor results in 2015 and some have made extraordinary returns for their clients over many years.

As the following chart – reprinted in the Financial Times and compiled by LCH Investments, the fund of hedge funds run by the Edmond de Rothschild group – reveals some managers have cumulatively earned tens of billions of dollars for their clients.

The list measures hedge fund traders by the total dollars they have made for investors since inception and shows that Ray Dalio of Bridgewater, the founder of the world’s largest hedge fund, reclaimed the top spot from the semi-retired George Soros, earning $45bn in net gains since Bridgewater’s inception in 1975. Roger Montgomery is the founder and Chief Investment Officer of Montgomery Investment Management. To invest with Montgomery domestically and globally, find out more.

Roger Montgomery is the founder and Chief Investment Officer of Montgomery Investment Management. To invest with Montgomery domestically and globally, find out more.

Hi Roger,

This point in your article ‘We made… [an] error in not trimming our Canadian Pacific position when it reached ~C$240 per share.’ is slightly related to a question I’d like to ask you.

At what point do you/does one sell? It’s easy to say buy at low prices, sell at high prices for a trader. But for the long term, fundamentals investor, it’s buy at good value and hold until..?

Eg One of your favourites Challenger, all things point to a great future and demographics are favourable for many years, but in 30 years the fundamentals wouldn’t look as rosy. At what point would you think it’s time to leave?

I don’t mean to specifically ask about Challenger, but any of the companies you think have a great long term future that you’ve blogged about (eg Altium, Seek, REA, HGG etc etc). Is there a point you’d identify as the turning point where the fundamentals don’t look positive, and sell a couple years before then?

(Another example, say you were a Woolworths/Tesco/etc investor (I’m not), and 15 years ago everything looked great. Would the first Aldi store be the time to sell? – that’s not very long term thinking, selling at the first sign of trouble.

Sell after Aldi’s 10th store? 100th?)

Hi Tristan, grab a copy of Value.able and read chapter on ‘Getting Out’ for a few ideas: https://shop.rogermontgomery.com/cart.php