How will artificial intelligence shape your retirement funds?

Parts of America’s industrial heartland are being transformed, and smokestacks and steel mills are being replaced by the scream of Graphic Proocessing Units (GPUs) housed inside concrete bunkers known as data centres. The transformation of parts of the U.S., such as Pennsylvania, is being mirrored globally as the world’s biggest tech names pour hundreds of billions into the physical infrastructure powering artificial intelligence.

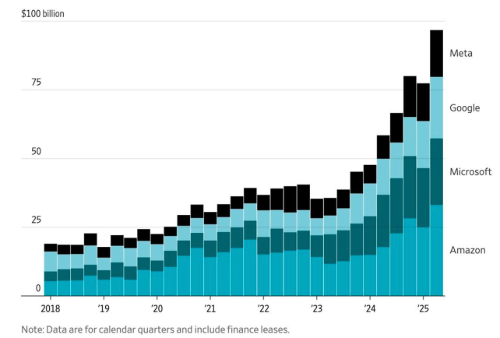

Figure 1. Quarterly capital expenditure (capex)

Source: Company reports, WSJ.

Of course, as we all know, this isn’t merely an upgrade to existing networks or a routine business cycle. Investors and commentators describe what’s occurring as the fourth ‘industrial revolution’[1].

Every revolution has reshaped the balance of power, redistributed wealth, and redrawn the competitive map, not just among the businesses engaged in the transformation, but also among the countries that foster, support and nurture them.

From code to concrete

In the past, Silicon Valley’s fortunes were built in tiny garages and on code – lean, scalable, and asset-light. But the artificial intelligence (AI) era is upending that script. Sure, there’s still code at the heart of it, but the largest technology companies in the world – Alphabet, Amazon, Microsoft, Meta, Apple, Nvidia, and Tesla – are now spending on infrastructure at a pace that rivals or exceeds anything seen during the dot-com or telecom booms.

As Figure 1., from The Wall Street Journal, reveals, in the most recent quarter alone, the so-called “Magnificent Seven” invested a staggering US$102.5 billion on capex (capital expenditure). The bulk of that came from Amazon, Alphabet, Microsoft, and Meta. These four companies are aggressively building data centres, securing chip supply, expanding manufacturing footprints, and locking in long-term energy deals.

As some have correctly observed, this isn’t just tech – it’s industrial policy, a ‘planet scale’ industrial build out. And as some analysts have estimated, AI-related capex has already outpaced the internet infrastructure buildout of the early 2000s as a share of U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

More importantly, unlike previous booms that became bubbles, it isn’t speculative capital funding the build-out. This time, it’s retained earnings and free cash flow.

The question is, are these Mega caps going to blow up billions or even trillions, or are they going to entrench their dominance for the next epoch?

The answer is probably somewhere in between.

Infrastructure is the new ‘moat’

Evidently, the thinking in the boardrooms of these companies is not who moves fastest but who owns the most.

It seems Warren Buffett’s competitive ‘moats’ are now measured in data centre acreage, power contracts, chip supply, and connectivity.

According to reports, Meta is building out its own AI training infrastructure after years of relying on cloud partners. Microsoft is investing billions in its Azure platform to keep OpenAI close and fend off rivals. Amazon continues to expand AWS globally, embedding itself deeper into the enterprise stack. Even Tesla is pushing into silicon and supercomputing to power its autonomous vehicle ambitions.

Meanwhile, Apple and Nvidia – though less visible in capex figures – are monopolising key parts of the supply chain through exclusive contracts and long-term investments with manufacturers like TSMC and Foxconn.

It’s no longer just about software. There is clearly a race to vertically integrate all parts of the AI technology stack – chips, servers, real estate, energy infrastructure, and logistics. It’s akin to Australia’s wealthiest iron ore magnates owning the mine, the railroads, the ports and the ships.

Who will win?

The big question for investors to answer is: who will win the race and dominate the competitive landscape in ten or fifteen years? That’s the tricky question, which if answered correctly, can mean you only need to make one investment to set you, your family and their families up for life.

In the background, AI-related infrastructure investment is estimated to have contributed more to U.S. GDP growth over the past two quarters than all household consumption combined. In effect, Big Tech has become a shadow stimulus engine, offsetting tariffs, inflation, and the impact of persistently high interest rates.

More importantly, and as is always the case, the benefits of this ‘AI-planet’ build-out aren’t evenly distributed. And the sources of funding may help decide who can survive when the sprint turns into a long-distance endurance event.

OpenAI, with its partnership with Microsoft and status as the poster child of generative AI, is widely accepted as a leader in the AI race. But it’s dependent on external funding and infrastructure. And according to the WSJ, its “Stargate” data center project has hit hurdles, while rivals such as Meta, are aggressively poaching talent with packages running into the tens of millions and even US$100 million.

Then there’s the conga line of AI startups, from which the 2030 leader may emerge. But is that even possible? These “neocloud” firms are often backed by venture capital or private equity and are trying to carve out niches in a space increasingly dominated by leviathans.

Business schools of the future will study whether the retained earnings of the giants were enough to entrench their dominance, whether they can simply buy any successful startups that threaten their dominance (and simply shut them down after purchase with the blessing of Trump’s pro-monopoly predisposition), or whether two kids in a garage was enough to upend the status-quo completely.

With respect to the giants’ monopoly or oligopoly status, there’s little indication from the Make America Great Again (MAGA) movement or the GOP (Grand Old Party, aka The Republican Party) that serious regulatory challenges are on the horizon. Competition among the top five or six firms remains fierce, but barriers to new entrants are rising even faster. And, in any case, most start-ups lack the balance sheet strength to fund massive infrastructure needs, which may hobble any ambitions of competing with the mega-cap gatekeepers.

Economically speaking

While plenty of pundits are suggesting this is another Gilded Age – think Andrew Carnegie, J.P. Morgan, and John D. Rockefeller, who reshaped the economy with steel, railroads and oil – these companies control enormous wealth, but they employ very few people. They are more efficient, but that’s because they don’t need people. Economically, their emergence may be more disruptive than constructive for the broader economy. Fewer individuals will be rewarded.

Meanwhile, the contest is also geopolitical. It’s well documented the U.S. and China are locked in a race for AI and advanced computing supremacy. While the U.S. has maintained a lead thanks to its chip design firms, cloud infrastructure, and innovation ecosystem, China is racing to catch up through massive state-led investment, state-sponsored industrial espionage, and a tight assimilation of industry by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). That the U.S. is feeling threatened is evidenced by Apple’s pivot to India for manufacturing, TSMC’s multi-continent expansion, and U.S. export restrictions on cutting-edge chips to China.

Returns from investing

For investors, the headlines about the latest AI chatbot or tech layoff miss the bigger story. Beneath the surface, a structural realignment is underway – one that clearly favours companies with impenetrable balance sheets and epochal cashflows, control over infrastructure, and the capacity to spend through any downturn.

The future winners might not be those with the best tech or the most intelligent algorithms, but those that can afford to build and own the roads, factories, and power plants of the digital economy.

If innovation can be blocked or stymied by ownership of the infrastructure, perhaps the future landscape is owned by the equivalent of a few shopping centre owners, where the retailers are fragmented and small and are shut down or purchased if they grow too big or too smart.

Thinking about how the competitive landscape will look in the future is the work needed to produce serious returns over the next decade or two.