How network effects are made – and broken

Look at any tech IPO nowadays and I bet you come across the term “network effects”. Network effects give a business a strong competitive advantage and are a source of value creation. So, what are they, how do they come about, and how can they be disrupted?

Let’s start with a definition. There are certain products whose value increases when more people use it (Reddit would be a little lonely without other users). Once a certain critical scale is reached, new users are attracted to the service due to the amount of people already on it. It becomes the “go-to” for a particular function. So much so that it can even become a verb – the Oxford English Dictionary added the verb “google” on June 15, 2006. Another successful example of network effects is the telephone – the appeal increased substantially once more of the population had home lines. This effect occurred again with mobile phones (though 90% of hospitals do still use pagers for communication). We have seen a crossover point when contacting by mobile became expected.

So, how do you go about creating network effects?

Step 1: Place 2 engineers in a garage.

Step 2: ???

Step 3: Network Effects!

All jokes aside, like any successful competitive advantage, network effects take years of hard work to create. Google was developed as an innovative search engine in 1996 and didn’t receive its first funding until 1998. It wasn’t until 2000 that Google began taking dominant share (it replaced Inktomi as the search results provider for Yahoo!). Wisetech (cloud-based software solutions provider for logistics) was founded in 1994 and has committed 3 million development hours over 15 years to reach its dominant market position and 6, 000 customers today. Aconex (cloud-based platform for construction/ engineering projects) was founded in 2000, expanded to the UK in 2004 and US in 2008 and has only now reached the scale of 70, 000 global users.

Now, how do you break it? Network effects are exceptionally hard to disrupt, but not impossible. One effective strategy is to first perfect a niche local market (much like if you’re trying to disrupt any incumbent with large scale). Whilst Google is the go-to search engine in most of the Western world (it has 80% global market share), creating a more localised approach can lead to successful business. Take Yandex – it has 62% market share in Russia (Google only 27%). Yandex concentrated on the Russian market where it tailored to the local language, created country-specific spam filters and differentiated itself as a media portal. This proposition was more attractive in the niche geographical market and Yandex was able to take dominant market share, much like Baidu has been successful in taking 80% market share of search engine advertising revenues in China.

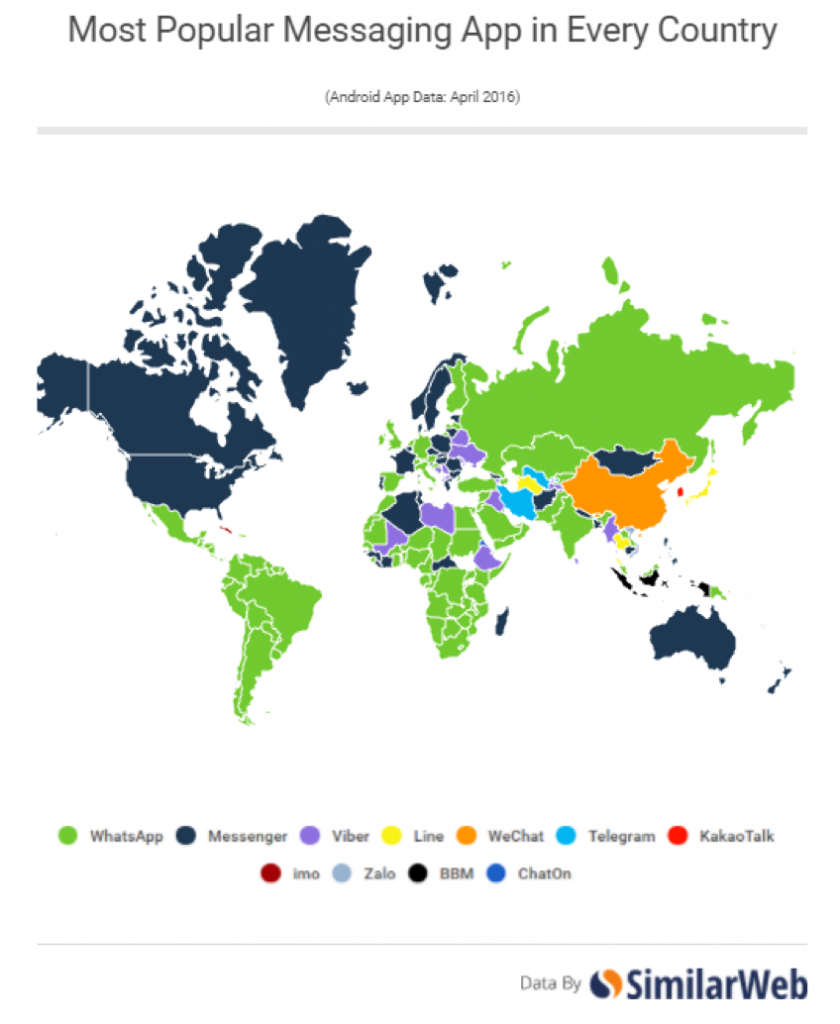

Geographical tailoring has also worked very effectively for messaging apps. Market share varies significantly by geography for this product: Similarly, Facebook gained market dominance by first tailoring to a niche market – but not geographically. It first developed a product exclusively for Harvard students, then introduced other universities. By first targeting the niche university market to establish itself, Facebook superseded MySpace by June 2009 (noting MySpace was the most popular site in the entire US in July 2006). Interestingly, even Facebook’s 1.94bn active users can be disrupted – I note my 10-year-old niece is already telling me “Facebook is for old people”. SnapChat and Instagram are clearly targeting niche younger markets.

Similarly, Facebook gained market dominance by first tailoring to a niche market – but not geographically. It first developed a product exclusively for Harvard students, then introduced other universities. By first targeting the niche university market to establish itself, Facebook superseded MySpace by June 2009 (noting MySpace was the most popular site in the entire US in July 2006). Interestingly, even Facebook’s 1.94bn active users can be disrupted – I note my 10-year-old niece is already telling me “Facebook is for old people”. SnapChat and Instagram are clearly targeting niche younger markets.

To sum up, network effects aren’t mythical unicorns. Like developing a new drug, or creating a new product, they take years of R&D to establish. Once sufficient scale is reached, they are hard to disrupt (particularly as profits can be re-invested in the product) and can become a valuable asset to a company. Even so, they aren’t invincible, and targeting niche markets can allow new players to disrupt incumbents and take dominant market share.

This post was contributed by a representative of Montgomery Investment Management Pty Limited (AFSL No. 354564). The principal purpose of this post is to provide factual information and not provide financial product advice. Additionally, the information provided is not intended to provide any recommendation or opinion about any financial product. Any commentary and statements of opinion however may contain general advice only that is prepared without taking into account your personal objectives, financial circumstances or needs. Because of this, before acting on any of the information provided, you should always consider its appropriateness in light of your personal objectives, financial circumstances and needs and should consider seeking independent advice from a financial advisor if necessary before making any decisions. This post specifically excludes personal advice.

INVEST WITH MONTGOMERY

Hi Lisa,

Greenwald argues that most competitive advantages are local in nature. However I am not sure that this applies to those maintaining a network effect when they enter “foreign” markets. However, I suspect there is a certain “nationalist” attachment to local companies. I dont mean that in a negative sense, but I believe many, but not all, governments would rather create a homegrown provider and in some cases are eager to assist in establishing and favouring a local company. It appears that service provider type companies do not penetrate overseas markets, in part because I think those governments favour their indigenous providers over those based elsewhere (usually the US).

I am interested to see if any or how many of these type of companies can be as successful overseas as they are in their home markets – REA, being one.

regards

Steve

Hi Steve,

Some interesting thoughts there. Greenwald also talks about different types of competitive advantages. What you’re describing would be a form of government protection (which can in specific circumstances be a competitive advantage). Large international players with network effects have a different kind of competitive advantage (taking Greenwald’s framework for Google, one could argue they have both an economies of scale advantage (providing strong fixed cost leverage) and a demand driven advantage (from the network effect)). To break down such an advantage, I very much agree with Greenwald that a localised approach (whether it be geographically or for a niche demographic) offers the best opportunity to compete – and a company is certainly better placed to do this if their local government is assisting them.

In terms of companies with localised network effects entering new markets, this is a different story. REA has strong network effects in the Australian housing market, time will tell if it can achieve the same in other markets.

Lisa