Golden opportunities?

When prices are collapsing, we tend to get very excited about the prospect of finding any proverbial babies that have been thrown out with the bathwater. Over the years we have built a number of quantitative and qualitative frameworks that rapidly analyse companies, in a range of sectors, in an attempt to quickly uncover potential investee candidates.

A current opportunity that serves as a typical example is the gold sector. It is, admittedly, an area into which we seldom venture (you might also recall Buffett’s view of gold only a year or two ago) given that these companies are the antithesis of the type of business we are after – which are those with competitive advantages such as an ability to raise prices even in the face of excess capacity. You wouldn’t, for example, see the share price of Woolworths or Carsales slide 60 per cent over a short time period as frequently as you do for gold companies.

With gold prices falling to levels not seen since the 1980s however, we are drawn to conducting a very short examination of the sector. The outcome of a few hours of data collection, analysis and discussion is not necessarily an investment decision!

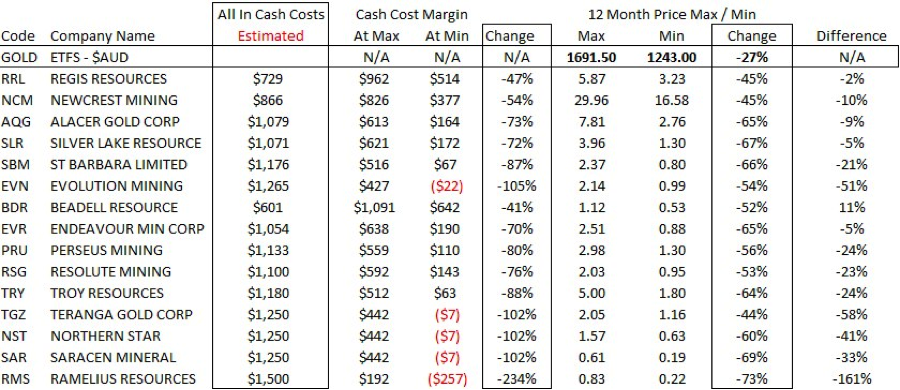

Let’s start with a look at the average estimated ‘All in Cash Costs’ of 15 gold producers, using data supplied to us by a range of analysts we know cover the sector well.

A number of gold producers will often quote a ‘cash cost’ in their regular investor update presentations. These are generally conservative figures, and frequently fail to take into account all of the costs associated with producing an ounce of gold, such as operating costs, royalties, sustaining capital expenditure and brownfields exploration, for example. Cash costs often don’t give a useful insight into a gold producer’s profitability at current gold prices.

We’ve estimated all of these costs, but excluded growth capital expenditure, greenfield exploration and corporate costs. Arguably, we have been generous by leaving out overheads – it’s not like the tooth fairy pays for these!

We then estimate each producer’s peak net (post cash cost) margin at the peak gold price over the past 12 months (A$1,691.5) and compare this to the margin at today’s gold price (A$1,243). This throws up some interesting findings.

By way of example only, EVN, TGZ, NST, SAR and RMS all had healthy margins at the 52-week high gold price.

Today, assuming the estimate of all-in cash costs is approximately correct, on a per ounce basis, these operations are unprofitable.

Unless one has the ability to forecast a higher gold price (something we lay no claim in being able to do), one takes on substantially more risk than is necessary by ‘investing’ here.

This leaves the profitable producers at current gold prices to focus on.

Businesses in which the percentage change in Cash Cost Margin is lower than the percentage change in the share price over the same period may toss up some opportunities – if you agree that the recently high prices correctly reflected the margins being made previously. It’s nowhere near perfect, but it’s a starting point for uncovering something resembling value in this sector.

Should, for example, a producer’s margin fall by 41 per cent, but the share price fall by 52 per cent, then it’s possible that the share price has overreacted – presuming of course that the previous high share price was the right starting point.

Conversely, if a margin decline of 105 per cent (now unprofitable) is matched with a share price decline of 51 per cent, then the share price may have understated the impact on the economics of the business. Short sellers rejoice!

Using this simplistic approach, we might be better off focusing any further hypothetical attention on BDR then EVN.

This analysis assumes that the estimates of all-in cash cost figures collected are in the ballpark. We say ballpark because we are merely attempting to be approximately right, not precisely wrong.

Regardless, it’s an interesting exercise to undertake every time the gold sector suffers one of its regular conniptions.

This post was contributed by a representative of Montgomery Investment Management Pty Limited (AFSL No. 354564). The principal purpose of this post is to provide factual information and not provide financial product advice. Additionally, the information provided is not intended to provide any recommendation or opinion about any financial product. Any commentary and statements of opinion however may contain general advice only that is prepared without taking into account your personal objectives, financial circumstances or needs. Because of this, before acting on any of the information provided, you should always consider its appropriateness in light of your personal objectives, financial circumstances and needs and should consider seeking independent advice from a financial advisor if necessary before making any decisions. This post specifically excludes personal advice.

INVEST WITH MONTGOMERY

Hi Roger, the stats for the major commodities are absolutely solid on this. The reasons I picked the gold price of $1,360 as the low for backing up the truck on gold stocks are many and varied, with one of them being that it is the price at which the highest cost miners will start to become marginal. The others relate to technicals/ physical demand/ sentiment indicators etc.

But if you look only at production costs, then based on current costs (of course, in a severe downturn for all commodities the cost of mining anything will go down – engineers and dump truck drivers taking a pay cut etc.) its almost impossible for the gold price to fall below $900 for more than a few days.

Kind regards,

Kelvin

Hi Roger, that is not true. Commodities do not generally trade below the lowest quartile of production costs. They may trade below the highest quartile costs at a given point in time for an extended period or even the average costs for a time, but very rarely below the lowest quartile costs.

Kind regards,

Kelvin

Looks like a battle of the stats Kelvin.

Hi Russell, thats a very sensible piece of analysis. The keys are low cost and low debt to survive a downturn. As long as the company can survive, the patient investor who buys during a downturn will make a fortune when the upturn comes. Its always been like this, across all commodities. There’s nothing new under the sun. Its a very repeatable process.

The other point to make is that just from your data on All in Cash Costs above, there is clearly a natural price point below which the gold price is unlikely to fall.

Kind regards,

Kelvin

Hi Kelvin,

You might remember the same argument being proffered about the iron ore price. Every single commodity, bar none, has traded for long periods below its cost. So don’t believe for a moment a commodity will always trade above the point at which a company must break even.