Fed rate cuts and market returns

In my professional opinion, there’s limited value that can be garnered from historical patterns, especially when those patterns examine the correlation between a single input and its result. Economies and markets are complex adaptive systems, and a myriad of inputs produce the market returns we subsequently experience. Just because something happened five, ten or fifteen times in the past, it is dangerous to conclude it will occur again next time.

With that caveat out of the way, it is nevertheless interesting to see whether said patterns have historically been consistent. Perhaps at some level, it might provide some insight into the range of possible outcomes, although it is worth remembering future experiences can blow previous experiences out of the water. As I noted in my book, Value.able, it is worth remembering Warren Buffett at this junction; “If past history was all that is needed to play the game of money, the richest people would be librarians.”

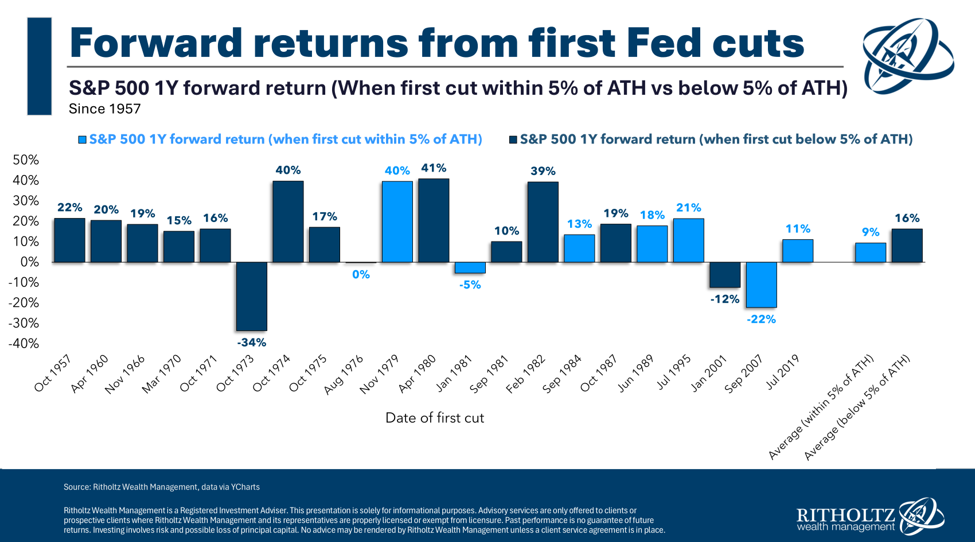

A U.S.-based wealth advice firm, Ritholtz Wealth Management, has examined the historical relationship between the first rate cut by the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) and subsequent returns (if indeed there is a relationship).

Their research team recently delved into the S&P500 historical data to examine how the stock market has performed following each initial interest rate cut by the Fed since 1957. They examined both the 12-month and 36-month subsequent returns, particularly noting instances when the market was within five per cent of its all-time high at the time of the rate cut – as it is now.

Historically, the stock market has tended to deliver solid returns in the year following the Fed’s first rate cut. Specifically, when the rate cut occurred near market peaks, the market was higher 12 months later in five out of seven cases (keep in mind seven cases do not make a statistically significant sample). Extending the analysis to a three-year horizon, the market was up in six out of seven similar instances.

Figure 1. Rate cuts and market response

These trends suggest that in the past, investors have, on average, fared well when the Fed begins to lower interest rates, especially when the market is already strong. This aligns with the intuitive understanding that easing monetary policy can stimulate economic growth and enhance corporate profitability.

These trends suggest that in the past, investors have, on average, fared well when the Fed begins to lower interest rates, especially when the market is already strong. This aligns with the intuitive understanding that easing monetary policy can stimulate economic growth and enhance corporate profitability.

However, as I said a moment ago, it is worth approaching these findings with a degree of caution, given the unprecedented nature of our current economic environment. Several factors distinguish today’s situation from past periods.

What is different? Well, firstly, the global economy is still adjusting to the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Secondly, trillions of dollars have been injected into the economy through government spending programs, and thirdly, the stock market has experienced an approximately 15-year bull run, one of the longest in history. Fourth, interest rates have fluctuated widely, creating less certainty; fifth, since June 2009, the U.S. has only experienced two months of recession, an unusually prolonged period of economic expansion; and sixth, the Fed now communicates its policies and intentions more openly than ever before, reducing the ambiguity that used to surround monetary policy decisions.

So, as with every past, first, rate cut, you don’t want to bet the farm that this year will be a great one too. That said, I note we have been bullish since 2002, and we have regarded a recession as an unlikely prospect.

Recall our opinion is that equities will do well in this and in 2025, provided the combination of positive economic growth and disinflation coexist. Since 1970 (noting caveats regarding history mentioned earlier!), that combination has been positive for innovative companies with pricing power, of which there is a myriad in the small-cap universe. And because small caps offer higher aggregate earnings growth for the next two years and are cheaper than their big-cap peers, we believe they are primed to outperform.

Nevertheless, given these unique circumstances, it’s challenging to predict whether historical patterns will hold true in the current context. While past data provides some optimism, the well-worn financial disclaimer “past performance is not a reliable indicator of future returns” is particularly relevant.

Finally, as Ritholtz also notes, the stock market has generally trended upward over most one- and three-year periods throughout history, regardless of Fed actions. This suggests that while rate cuts may coincide with positive market performance, they are not the sole driving factor.

And let us not forget that while human behaviour remains a constant in economic cycles, the inherent unpredictability of human decision-making will always add a layer of uncertainty to market forecasts.