Do we need economists and economic commentary?

Let’s suppose you employed someone to flip coins for you because you believed they were a “lucky” flipper. Would you keep employing them, if after 34 years you found that they flipped winners only half the time? Anyone with a penchant for maths or an interest in Martingale may of course be quite satisfied, but the rest of the population would feel the lucky flipper was of little use at all.

And so we come to economists. With so much of business “news” filled with commentary about the economy and analysis of it, I for one would certainly like to know whether any attention needs to be paid.

My friends Ashley Owen and Chris Cuffe published some interesting findings on Cuffelinks today, regarding the relationship between stock market returns and the strength of the economy.

One of the unquestioned assumptions in our industry is that economic growth, or expectations of it, drives stock prices. One could certainly mount a reasonably convincing argument that economic growth drives company profits, which in turn, drives share prices.

Perhaps surprisingly, Ashley finds: “There is no statistical correlation between economic growth and stock market returns, either at a global level or in individual countries.”

So there!

Ashley continues, commenting that “only rarely does above average world economic growth coincide with above average stock market returns. In only two of the past 34 years since 1980 has this been the case – 1988 and ’06. Also, in only six years has below average economic growth coincided with below average stock market returns – ’81, ’90, ’92, ’01, ’02 and ’08.

In fact, at least half of the time when economic growth was above average, stock market returns were below average, and at least half of the time when economic growth was below average – including in recessions – stock market returns were above average.”

So half the time, if the economy is strong, the stock market will be also, and half the time – it won’t be.

Flip a coin!

So, it is wise to be listening to all the waffle about employment, interest rates, inflation and the like? Well, yes and no. You see, over the very long run there is a relationship, but it isn’t between economic growth as measured by GDP and the stock market. There is, however, a relationship between interest rates combined with corporate profits and stock market returns.

Carol Loomis and Warren Buffett discussed this relationship in a 2001 edition of Fortune magazine.

Reaching the same conclusion as Ashley Owen, Buffett noted that between 1964 and ’81, the stock market rose just one tenth of a per cent, and during the same period the economy expanded almost four-fold. Then, between 1981 and ’98, when the economy grew by a more modest 177 per cent, the US stock market rose by ten-fold!

Here’s an excerpt from the 2001 Fortune article:

“The last time I tackled this subject, in 1999, I broke down the previous 34 years into two 17-year periods, which in the sense of lean years and fat were astonishingly symmetrical. Here’s the first period. As you can see, over 17 years the Dow gained exactly one-tenth of one percent.

Dow Jones Industrial Average

- 31 December, 1964: 874.12

- 31 December, 1981: 875.00

And here’s the second, marked by an incredible bull market that, as I laid out my thoughts, was about to end (though I didn’t know that).

Dow Jones Industrial Average

- 31 December, 1981: 875.00

- 31 December, 1998: 9181.43

Now, you couldn’t explain this remarkable divergence in markets by, say, differences in the growth of gross national product. In the first period – that dismal time for the market – GNP actually grew more than twice as fast as it did in the second period.

Gain in Gross National Product

- 1964-1981: 373%

- 1981-1988: 177%

So what was the explanation? I concluded that the market’s contrasting moves were caused by extraordinary changes in two critical economic variables – and by a related psychological force that eventually came into play.

Here I need to remind you about the definition of “investing”, which though simple is often forgotten. Investing is laying out money today to receive more money tomorrow.

That gets to the first of the economic variables that affected stock prices in the two periods – interest rates. In economics, interest rates act as gravity behaves in the physical world. At all times, in all markets, in all parts of the world, the tiniest change in rates changes the value of every financial asset. You see that clearly with the fluctuating prices of bonds. But the rule applies as well to farmland, oil reserves, stocks, and every other financial asset. And the effects can be huge on values. If interest rates are, say, 13 per cent, the present value of a dollar that you’re going to receive in the future from an investment, is not nearly as high as the present value of a dollar if rates are 4 per cent.

So here’s the record on interest rates at key dates in our 34-year span. They moved dramatically up – that was bad for investors –in the first half of that period, and dramatically down – a boon for investors – in the second half.

Interest rates, Long-term government bonds

- Dec. 31, 1964: 4.20%

- Dec. 31, 1981: 13.65%

- Dec. 31, 1998: 5.09%

The other critical variable here is how many dollars investors expected to get from the companies in which they invested. During the first period, expectations fell significantly because corporate profits weren’t looking good. By the early 1980s, Fed Chairman Paul Volcker’s economic sledgehammer had, in fact, driven corporate profitability to a level that people hadn’t seen since the 1930s.

The upshot is that investors lost their confidence in the American economy: They were looking at a future they believed would be plagued by two negatives. First, they didn’t see much good coming in the way of corporate profits. Second, the sky-high interest rates prevailing caused them to discount those meager profits further. These two factors, working together, caused stagnation in the stock market from 1964 to ’81, even though those years featured huge improvements in GNP. The business of the country grew while investors’ valuation of that business shrank!”

So what should we do about all the economic noise filling the airwaves, the papers and investment newsletters?

Simply have a look at the long-term trends for interest rates and then ask whether they are generally going to trend lower or higher over the next five to ten years.

Secondly, ask whether profits, as a proportion of the economy, are trending higher or lower.

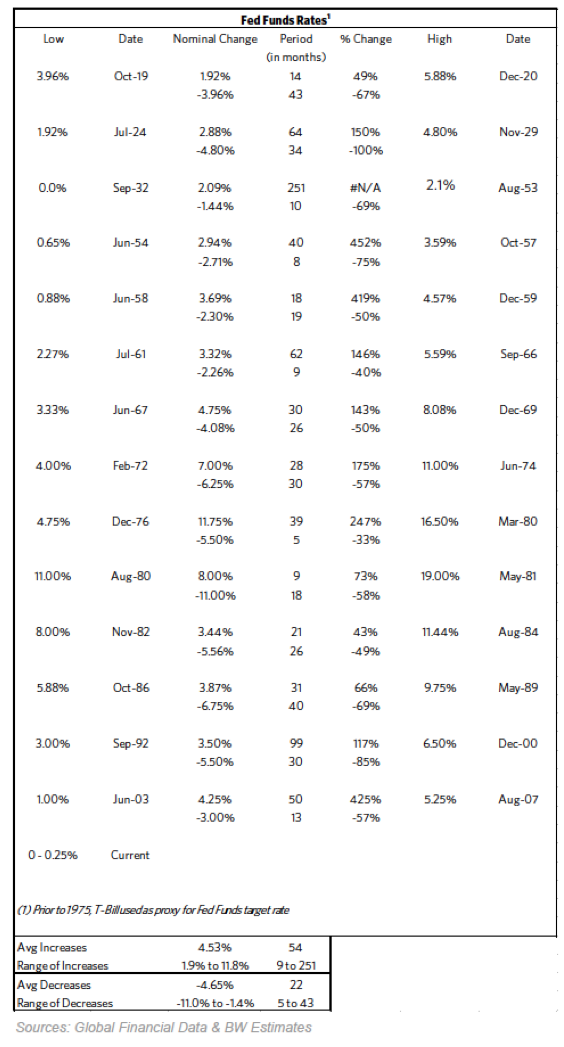

On the interest rate side of the equation, it may be worth examining the below table. Produced by Ray Dalio of Bridgewater Associates, it’s eye-opening; especially in light of the recent steepening of the yield curve in the US. The trend for rates now appears to be higher, or as experts like to suggest – normalising!

Table 1. US interest rate trends since 1919

Buying big, so-called “blue chips”, and shoving them in the bottom drawer on the back of the mistaken belief that it’s “time in the market” that covers a multitude of sins, will be a mistake.

Being a nimble investor, willing to focus selectively on the very highest quality companies and the very best value, and being willing to sell and raise cash when stock prices reflect irrational exuberance, will be important in the next five to ten years. And it will be more important than knowing what the economy is going to do next week, next month or even next year.

What an insightful commentary!! I have learned some very useful things from this article. Thank you Roger!!

Thank you very much Roger for this brilliant piece.

Kelvin