Consumer wealth effect – Another nail in the coffin for retail spending.

Consumer spending has risen strongly in the past year, spurred on by property owners feeling richer due to higher house prices. This is called the household wealth effect. But with house prices looking toppy, should retailers – and investors – be concerned about the effects of a property market correction?

As readers know, we are very negative on both Australian retail companies and the property market. The development of both these sectors is linked, but the exact level of linkage is hard to quantify.

We were therefore interested to read the recent Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute report “Housing prices, household debt and household consumption” showing the impact on consumer spending from the wealth effect from higher property prices (i.e. consumers spend more when they feel wealthier even though the wealth is tied up in illiquid assets).

The key findings from the report are:

- There are different behaviours in different age groups to the change in house prices. The older you are, the more likely you are to increase your spending due to a perceived wealth effect. This makes intuitive sense, as your underlying cashflow is better due to a lower level of mortgage, and lower costs (e.g. you don’t have kids in the house anymore). Due to a lower level of mortgage, you are also more likely to be able to take out additional loans on your property.

- There is a BIG difference between owner-occupiers and owner-occupiers who are also investors. Investors are about two times more sensitive to changes in house prices compared to people who do not own an investment property. This makes intuitive sense as these people are feeling more wealth effect due to their increased exposure to property values.

- Investors (or rather speculators) with high level of loan-to-value ratios are more likely to increase their consumption compared to owner-occupiers. That is, investors are treating investment property more like a credit card than a necessary utility or a long-term cash generating asset.

- Overall, on average across all property owners, a household is likely to increase its annual consumption by $31/week or about $1600 per year, for every $100,000 increase in value of their house or about 1.6% all else being equal.

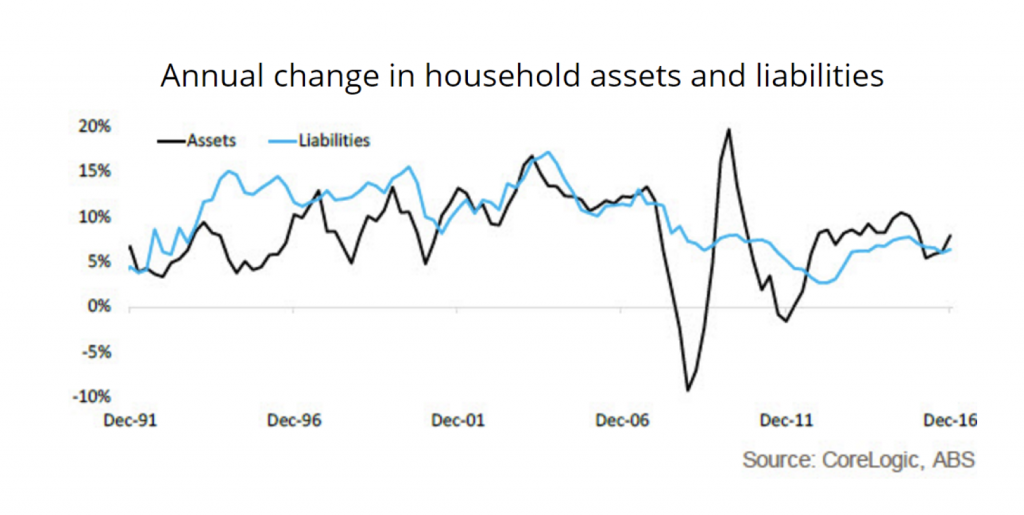

If we look at the value of the total residential housing stock in Australia, it is (according to ABS) about $6.1 trillion at the end of 2016 and it has been growing by about 8% per year since 2012.

This means that the total increase in consumption for 2016 from the increase in house values was about $6.1 trillion *8%*1.6% = $7.8 bn. The previous years were slightly smaller due to the base effect, but let’s say the wealth effect is $6-7 bn on average per year.

Total retail turnover in Australia was in 2016 $122 bn and it has been growing by about $4 bn per year.

Now, all the increases in household consumption are not going to be spent in Australian retail shops (the overseas holidays etc. will take their share!). We are though prepared to wager that quite a lot of the growth in retail spending over the last 5 years has come from the wealth effect of people feeling wealthier due to the increases in house values.

Given that we are bearish on the development of property prices and consider at least Sydney and Melbourne to be in significant bubble territory, we are hence very careful with projecting any growth in retail spending. Even if we only get a flattening out of property prices, the impending entry of Amazon means that Australian retail companies will have to contend with increased competition without the help of the steroid injection of property wealth related consumption spending. On top of this, we have very stagnant real wage growth and significant upcoming increases in non-discretionary costs like electricity, which together paints a very dire outlook for retail spending.

This post was contributed by a representative of Montgomery Investment Management Pty Limited (AFSL No. 354564). The principal purpose of this post is to provide factual information and not provide financial product advice. Additionally, the information provided is not intended to provide any recommendation or opinion about any financial product. Any commentary and statements of opinion however may contain general advice only that is prepared without taking into account your personal objectives, financial circumstances or needs. Because of this, before acting on any of the information provided, you should always consider its appropriateness in light of your personal objectives, financial circumstances and needs and should consider seeking independent advice from a financial advisor if necessary before making any decisions. This post specifically excludes personal advice.

INVEST WITH MONTGOMERY

Hi Jack,

I agree that for the overall economy it would probably (only my uninformed opinion, I am not a macro economist) have been a better outcome if the stimulus activites over the last decade had benefited both the providers of capital and the providers of labour a bit more equal.

The central banks around the world have though only a few tools at their disposal. Mandating the level of wages and wage growth is not one of them (which i think we should be happy for, it was tried for quite a long time in the Sovjet Union with not very good result :-). They therefore have to use the tools they have and as they are in charge of monetary policies, what they can influence is the availability and cost of debt with the aim to create conditions that are conductive to economic growth. It is though a fact that the people who owns capital will always benefit more from easy availability of debt than the people without capital and hence the policy makers have to rely on the “trickle-down effect” of economic growth creating good jobs for the people without capital so that they have the economic resources to consume and hence keep the economy going.

The price of labour will (and should be) decided by supply and demand just as any other product. I believe that the best action of policy makers are to focus on creating conditions that are conductive for successfully growing companies in high-value added sectors (i.e. sectors that contains specialised skills and that are hard to replicate by others) and stimulate investments into productive assets (i.e. not create an environment that leads to speculation in unproductive assets like residential housing). This can be through correct tax incentives or through making sure that the work force acquire the right skills through education etc. I do not believe that policy makers should try to fiddle with the natural price mechanism for labour directly nor should they stimulate consumer demand by handouts (e.g. baby bonus etc.) as it will only have unintended harmful consequenses.

Hi Andreas,

Thanks for the article. I would like to know your take on What should happen for consumers to have wage growth. I am starting to feel that what the central banks have been doing with QE could have been replaced by causing a wage growth in the society. That would have triggered more spending and thus stimulating the economy. With buying bonds, the money that is injected into the system seems to have gone to bond issuers and holders instead.