Are interest rates hurting rather than helping?

The chief economist at the Bank of England recently made a speech in which he mentioned the increase in capital management (ie. increased dividend payout and buy back activity) by public companies as having consequences for economic growth.

The speech argued that public company decision making is too short term focused, with the primary objective being to lift the share price. Senior management incentivisation through the use of equity grants is a major factor in driving this short term focus. Between 1980 and 1994, the value of stock options issued to CEOs of large US companies increased 700 per cent compared to 100 per cent growth in salaries and bonuses. This was designed to better align the management interests with shareholder interests. The shift in remuneration toward share based payments has continued to increase since 1994 and mirrored in Australia.

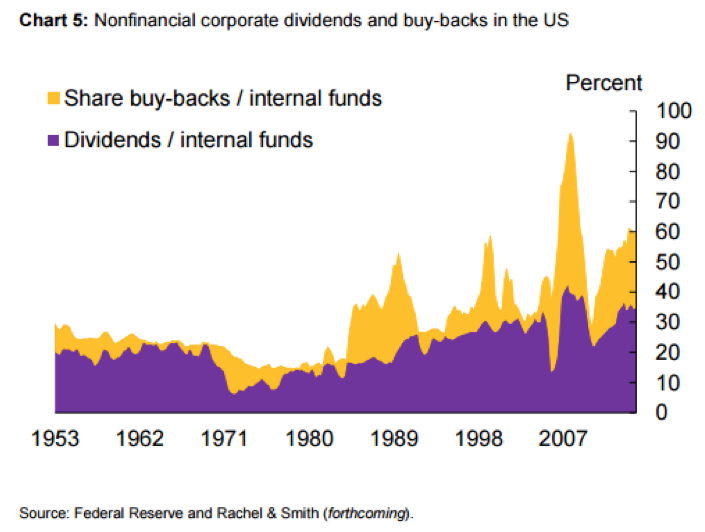

The chart below shows the increase in the proportion of profits distributed by US companies to shareholders through dividends or buybacks since 1980.

The incentive for companies to return capital through dividends is even greater in Australia as a result of the dividend imputation system, whereas retaining capital results in undistributed tax credits. Essentially, a company can only reinvest 70 per cent of the amount a domestic shareholder would receive as a grossed up value through a dividend.

The incentive for companies to return capital through dividends is even greater in Australia as a result of the dividend imputation system, whereas retaining capital results in undistributed tax credits. Essentially, a company can only reinvest 70 per cent of the amount a domestic shareholder would receive as a grossed up value through a dividend.

The view expressed is that management’s increased short term share price focus is leading to a diversion of capital from reinvestment for growth and the long term health of the business back into shareholder hands, believing that lifting short term returns to shareholders will be more powerful in driving up the share price than investing for long term growth.

The macroeconomic consequence is lower business investment, which will reduce economic and earnings growth in future.

At a speech in New York in April, the Governor of the RBA, Glenn Stevens, lamented that lower interest rates had not translated into lower hurdle rates of return applied by company executives and directors in assessing potential investments. As we discussed in an earlier blog, the RBA has been disappointed with the impact of rate cuts on private sector investment.

However, businesses need to assess the cost of capital on a long term basis, not on the back of a short term risk free cost of debt. For similar reasons, the Australian 10 year bond rate has only fallen by around 1.5 per cent while the overnight cash rate has fallen 2.75 per cent since the RBA started easing in November 2011.

Additionally, companies need to assess the value of an investment based on the risk in the economy and the market. The decision to lower interest rates has arisen as a result of the weakening in the outlook for economic growth. Hence the risk adjusted rate of return is more likely to have increased than fallen.

Additionally, the lack of change in the hurdle rate used by companies to assess projects could actually be explained by investor behaviour in the face of falling short term interest rates.

The flipside of lower short term interest rates is that it increases the value of income to capital holders. With bank deposit rates falling, those relying on income from investments will look to other sources of income to make up for the cash flow deficit created by lower deposit rates. As a result, money flows into stocks with higher yields and payout ratios.

As noted earlier, company management and boards are far more incentivised around the share price performance these days. The increased demand and value placed on yield by shareholders increases the pressure and incentive for companies to redirect earnings from reinvestment for growth to dividends to drive up the share price. Essentially, the increased value placed by the market on dividends could in fact be a significant reason why companies have not lowered project hurdle rates, as a project now needs to be even more attractive to justify retaining the capital rather than paying out an increasingly valued dividend.

Hence, lowering interest rates could actually be worsening the problem of weak business investment rather than helping it.

Stuart Jackson is a Senior Analyst with Montgomery Investment Management. To invest with Montgomery domestically and globally, find out more.

This post was contributed by a representative of Montgomery Investment Management Pty Limited (AFSL No. 354564). The principal purpose of this post is to provide factual information and not provide financial product advice. Additionally, the information provided is not intended to provide any recommendation or opinion about any financial product. Any commentary and statements of opinion however may contain general advice only that is prepared without taking into account your personal objectives, financial circumstances or needs. Because of this, before acting on any of the information provided, you should always consider its appropriateness in light of your personal objectives, financial circumstances and needs and should consider seeking independent advice from a financial advisor if necessary before making any decisions. This post specifically excludes personal advice.

INVEST WITH MONTGOMERY

What almost no one realizes, however, is that interest rates are a price, the price of money. Like any other price, interest rates perform both a signaling and a coordination function. Interest rates coordinate the actions of savers and borrowers: higher interest rates attract savers, lower interest rates attract borrowers, and the market interest rate provides an equilibrium between saving and borrowing. The interest rate also signals the availability of funds: lower interest rates signal an abundance of loanable funds, while high interest rates signal a paucity of funds. As interest rates rise, more people save and fewer people borrow; as interest rates fall, fewer people save and more people borrow. Lower interest rates also tend to favor longer-term, more capital-intensive projects. Projects which might not be profitable at eight percent interest rate may suddenly become profitable if the interest rate drops to three percent.

https://www.lewrockwell.com/2012/09/ron-paul/the-myth-of-a-us-free-market/

The fundamental fact of the interest rate is that it is a discount of the future.

“better an egg today than a hen tomorrow”

Usually, people discuss interest in relation to money. Interest is said to be the price of money. This concept is incorrect if it is said to apply only to money. Interest is a discount applied to every stream of benefits, or as economists say, stream of income.

Different people apply different rates of discount to streams of income. Some people are intensely present-oriented. They want action now. They don’t want to wait.

Other people are comparatively future-oriented.

The central fact of interest is this: we discount the future. Item A is worth more to us today than it is a year from now. We have a year to enjoy it. We therefore have to be offered compensation to persuade us to forfeit the use of it. This is also true of item B.

https://www.lewrockwell.com/2004/05/gary-north/interest-rates-in-one-lesson/

So, Japanese investors have stopped saving. They are cashing out. They are selling their investments, especially government bonds. The nation that used to save 23% per year is now cashing out by 1.3%.

But who needs savings, when you have a central bank that creates wealth out of nothing?

Ludwig von Mises was right back in 1948. Keynesianism is an economic philosophy of stones into bread.

In the early phases of Keynesianism, it looks as though the miracle of stones into bread is real. But at the end, it will be revealed as a system of bread into stones. King Solomon put it best 3,000 years ago. “Bread of deceit is sweet to a man; but afterwards his mouth shall be filled with gravel” (Proverbs 20:7). Keynesianism is deceit by means of graphs, equations, and jargon.

https://www.lewrockwell.com/2014/12/gary-north/the-japanese-no-longer-save/

“short-termism” – in our political and business classes – I’d say it is at the heart of most of the major issues currently facing our modern western democracies…

To address it, we need to shift incentives more toward the long term – align business leaders’ payoffs with long term performance indicators for the business, and payoffs for politicians and political parties with long term performance indicators (both social and economic) for the nation…

Not easily done, especially in the latter, but increasingly urgent I feel…

Stuart if we have a study of recessions and depressions and the response of the central bank you will see that the response is always to lower rates. Has it ever worked even once? Did it end the great depression? Has it created inflation, growth or increased business activity in Japan over the last 25 years at 0.1%. Has it worked this time? If the answer is no then why do they keep repeating the same mistake over and over again?

Hi Aaron, I would agree. Looking at the last 20 years, we have seen a long period of largely accommodative monetary policy settings around the world. This has tended to drive asset price inflation rather than consumer prices. This is partially due to western economies importing goods and services deflation through increased sourcing from emerging markets. Additionally, there is a view that with western economies increasingly being driven by higher value added technology development, the physical capital requirements of the economy have diminished over time. As a result, the traditional view that lower interest rates lead to increased investment in capital goods to lift productive capacity begins to become less relevant, and capacity growth is far less capital intensive. An example is e-commerce replacing traditional print media and retail. Growth in e-commerce volumes doesn’t require the same amount of incremental capital to support it as printing presses or retail stores/malls.