Are inflationary pressures heading in the right direction?

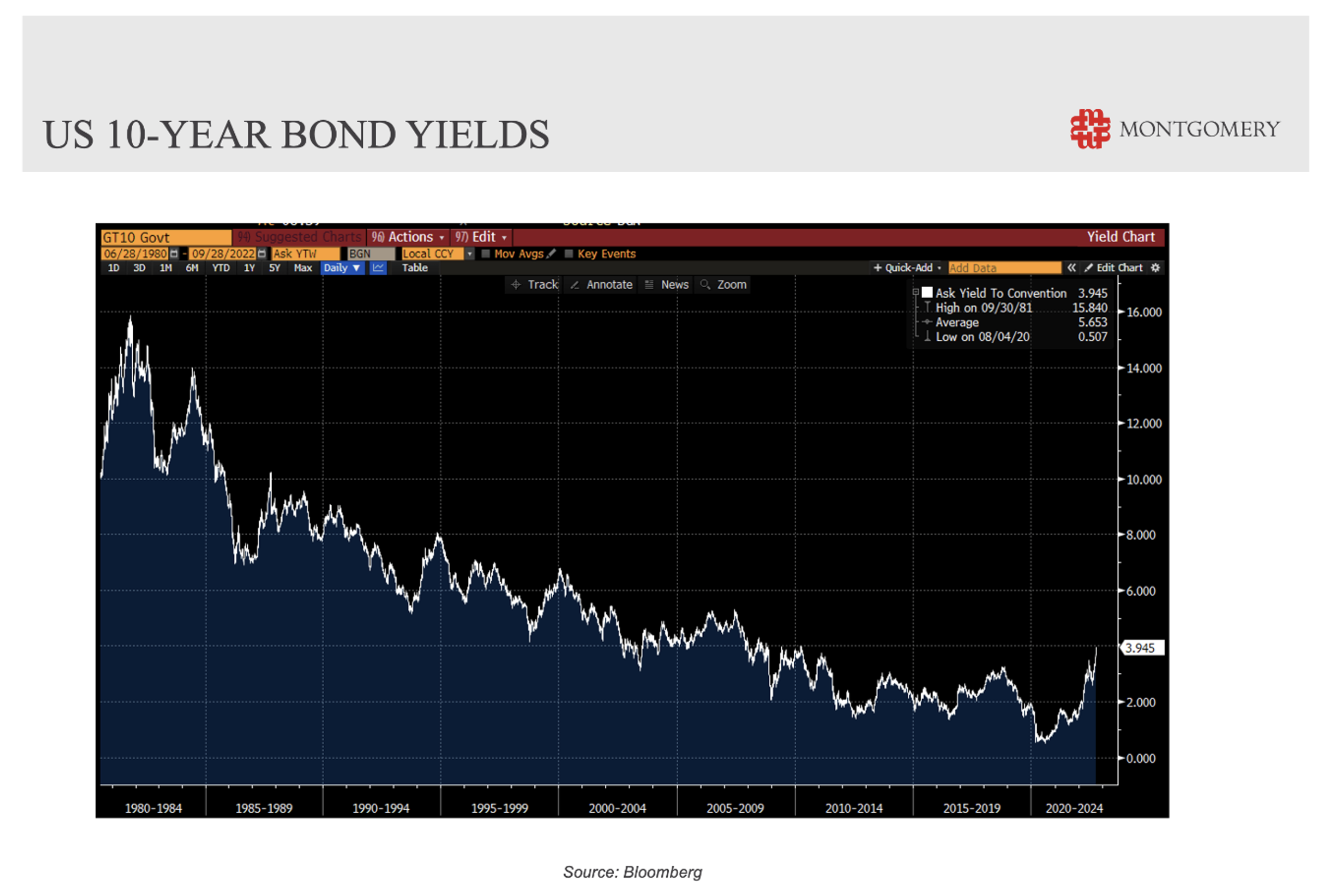

On the back of exiting the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war, inflation has been rearing its ugly head and in the case of many developed economies it is growing at the highest level since September 1981, when U.S. ten-year Government bonds yields challenged 16 per cent.

An enormous rally famously started when Governor of the U.S. Federal Reserve, Paul Volker, set out to break the back of inflation which had been building up in the 1970s with oil shocks and dramatic wage rises. And the severely tightening monetary conditions led to a severe recession as well and what in hindsight was an extraordinary buying opportunity.

As U.S. Government Bonds went on an almighty 39-year rally, it is little wonder most other asset classes have performed superbly with the valuation tailwind, largely assisted by Central Banks quantitative easing and persistently low inflation over the 2000s and 2010s decades.

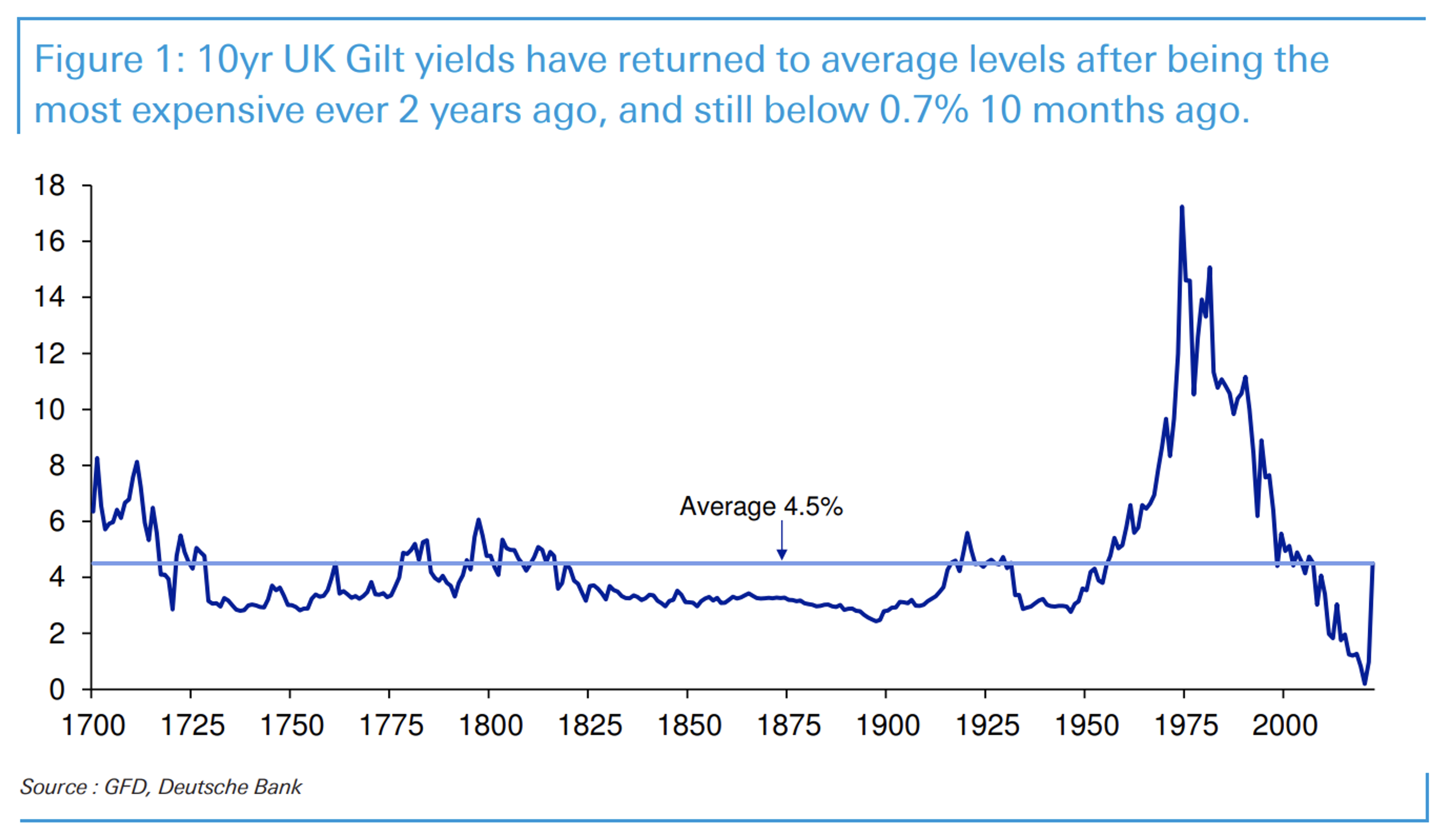

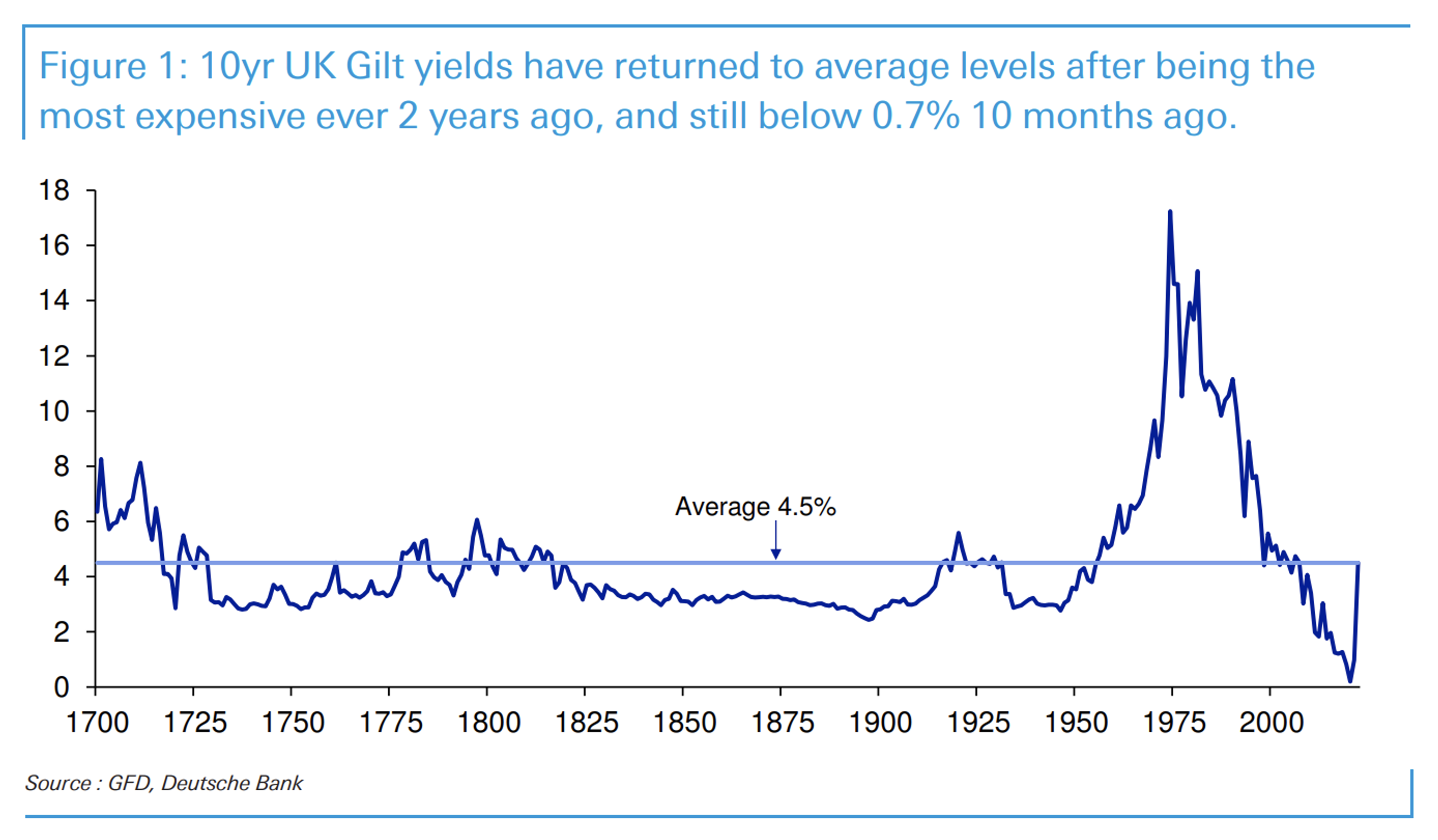

On 4 August 2020 UK 10-year Gilts were trading at 0.08 per cent, the lowest level in over 300 years of data relating to UK Government borrowing costs. At the same time U.S. ten-year Treasury bonds troughed at 0.51 per cent. Unsurprisingly, many assets have enjoyed an extraordinary valuation – whether they were producing cashflow or not – as markets made the assessment that inflation was dead, interest rates would remain near record lows, and credit availability was plentiful.

However, economies have exited the COVID-19 pandemic with supply constraints, close to record low unemployment placing pressure on wages, sky-high gas, electricity, food and rental costs resulting in a shock – where inflation in many economies is suddenly challenging 40-year highs. This has been a painful 26-month turnaround in inflationary expectations.

In one of the biggest crashes in the history of Developed World Government Bonds, the UK ten-year bond yields have jumped to 4.50 per cent, whilst the U.S. ten-year bond yields have jumped to 3.95 per cent, after recently breaching 4.00 per cent – see the graphs below.

While these inflationary pressures might soon be heading in the right direction, the thesis – that the combination of globalisation, digitisation and technological improvement, demographics and consumer indebtedness would be deflationary – might be correct over the longer-term, it has proved shockingly inaccurate more recently.

That said, these “deflationary pressures” will surely mean most Developed World Central Banks do not have to tighten their official cash rates very much before their populations start screaming in financial pain. And a quick assessment of the New Zealand economy gives readers some insights into this pain.

You can read my comments on New Zealand in this post:

WHAT NEW ZEALAND’S RATE TIGHTENING CYCLE TELLS US