A framework for making good investment decisions

Warren Buffet has famously advised that “To invest successfully over a lifetime does not require a stratospheric IQ, unusual business insights or inside information. What’s needed is a sound framework for making decisions and the ability to keep emotions from corroding that framework.” In this article, I’ve provided a basic framework to help you make sound investment decisions.

Let’s start with another Buffett aphorism:

“Your goal as an investor should simply be to purchase, at a rational price, a part interest in an easily-understandable business whose earnings are virtually certain to be materially higher five, ten, and twenty years from now.”

Let’s break that quote down to highlight two of the quote’s four key offerings.

The first is a ‘rational price’, and the second is a business whose earnings will be ‘materially higher in five, ten, twenty years from now’.

Today’s market lows reflect great fears

As one finance reporter noted, ‘We now face serious global headwinds and challenges with elevated inflation. Growth is slowing globally. And energy and food prices have risen, driven partly by Putin’s terrible war in Ukraine and the pandemic’s lingering effects abroad. Climate change continues to devastate communities, exacerbating energy and food shortages in Europe and across the world.’

There are many concerns and influences for investors to fear. The result is investors aren’t willing to pay as much for a dollar of a company’s earnings as they were when they were optimistic and could only see bright prospects and feared missing out on them.

Sentiment towards the stock market is forever changing

When investors are optimistic they’re willing to pay a very high price and when investors are depressed or despondent they’re only willing to pay a very low price. Even though the underlying business is stable and may have changed nothing, the price investors are willing to buy and sell it can change dramatically.

One measure of this sentiment – we can also call it popularity – is the price-to-earnings multiple, also known as the P/E ratio or, simply, the P/E.

If a company is earning $1.5 million of profit after tax and it has 300,000 shares on issue and held by various shareholders, the company is said to be earning $0.50 per share.

Now, these 300,000 shares trade on the stock market and every day they rise and fall. Interestingly, the business doesn’t change very much day-to-day. In fact, it just keeps making the same widgets and selling them to the same customers. But despite this stability and reliability, the share price is never stable.

On days when a country’s central bank decides to raise interest rates, or a country invades another, the shares could fall dramatically. The next day, a central bank may simply raise rates by less than was expected, and the same shares could surge. Even though these exogenous events have nothing to do with the company, and even though they may have no impact on the company, its revenues, its customers or its profits, the shares will ride around like crazy reflecting the greed and fear of the investors who are buying and selling them.

So, on a day investors are happy and excited, the shares in our hypothetical company might trade at 30 times the earnings. Thirty times 50 cents equals $15.00, so on an exuberant day, the shares might trade at $15.00 and be on a ‘P/E’ of 30 times.

Conversely, if bad news about the world, inflation, or the economy is released, investors might only be willing to pay a multiple of eight times the earnings and the shares would be trading at $4.00.

Wild swings can occur in the multiple investors are willing to pay for a company’s dollar of earnings, even though the underlying business might be very stable.

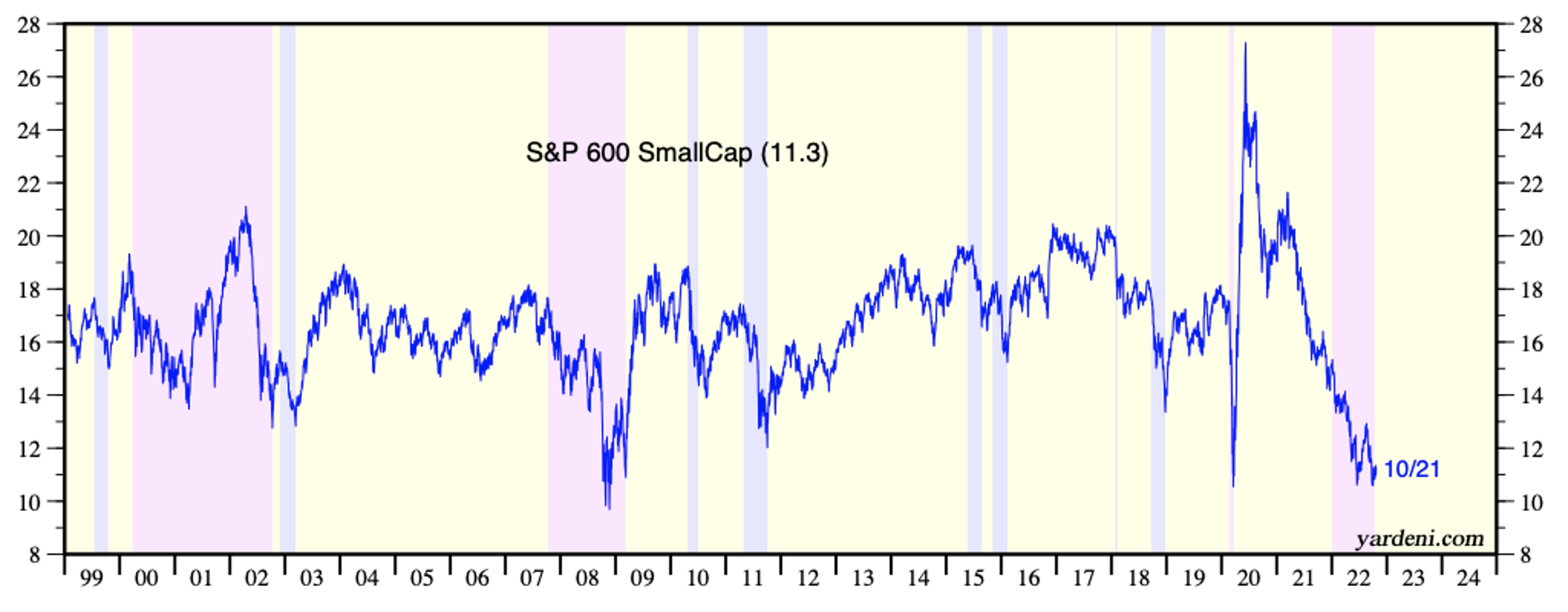

Figure 1. illustrates the change in the P/E ratio of the S&P600 small cap index, and reveals just how much the P/E ratio can swing around, and how frequently.

Figure 1. P/E Ratio S&P600 Small Cap Index to 21 October 2022

You might be drawn to several observations about price-to-earnings ratios but the two I want to bring to your attention are first, how frequently the P/E soars and plumbs the depths and second, where sentiment, as measured by the P/E ratio, is today.

As I noted earlier, investors currently believe they have a great deal to fear and hence they simply aren’t willing to pay a very high multiple of earnings. Even though the concerns will pass – to be replaced by new concerns – investors aren’t willing to think too far into the future, instead, they’re stuck in the current rut.

What Figure 1 reveals is that these periods of despondency have occurred before and each time sentiment has recovered. That will probably be what occurs this time.

Of course, the P/E ratio is made up of the price and the earnings. When prices change and the earnings remain the same, the P/E ratio will change. But it is also the case that if prices don’t change but the earnings change, the P/E ratio will also change.

A couple of quick examples to demonstrate

If a company’s earnings are $10 per share and the price is $135, the P/E ratio is 13.5 times. If the earnings remain at $10 but the price halves to $67.50 the P/E ratio will be 6.75 times earnings.

What if the price doesn’t change but the earnings per share does? If the price remains at $135.00 per share and the earnings halve from $10 per share to $5 per share, the P/E ratio will rise to 27 times earnings.

I have seen the second scenario play out, particularly during recessions. What typically happens is share prices fall dramatically ahead of a recession, such as we saw in 1999/2000 and perhaps even today. The P/E ratio falls, but earnings don’t change much. Share prices then stabilise, but as the recession takes hold, company earnings are impacted and the ‘E’ in the P/E ratio falls. The result is that P/E ratios rise but the share prices don’t change dramatically.

Of course, the outcome of this latter development is that shares look expensive again because the P/E has risen, sometimes dramatically. Amid a recession, it is difficult to imagine coming out the other side of it. But this is how investors must think. The share price falls have already largely accounted for the recession, so even as the earnings decline, investors aren’t willing to sell their shares at any lower prices.

Once again, there is every possibility we have reached this point. Note in Figure 1., today’s P/E ratio is almost as low as it was during the Global Financial Crisis and lower than during the COVID-inspired sell off.

Investing in growth

One thing we haven’t touched on is how an investor can mitigate some of the risks associated with investing today amid fear of recession and earning declines. By focusing their attention on those companies Warren Buffett referred to in the earlier quote – companies whose earnings will be materially higher in five, ten and twenty years from now – investors can reduce the risk of further share price falls.

Here’s the result of some simple arithmetic. If you buy a company whose earnings grow by 15 per cent per year over the next five years, and you buy and sell the shares of that company on the same P/E ratio, your return will equal the earnings growth rate of that company. In other words, if, for example, you buy the company’s shares on a P/E of 10 and you sell them on a P/E of ten, and the earnings per share grow by 15 per cent, per year, your returns will also be 15 per cent.

And here’s the evidence of some more simple arithmetic. If the P/E ratio of that company falls by 25 per cent at the time you sell the shares in five years, your return will still equal nine per cent per year.

In other words, you will still generate a respectable return from owning the shares for five years, provided the earnings grow by 15 per cent per year and even if the P/E drops from say, 20 times when you purchased the shares to 15 times when you sell.

And that’s the second part of Warren Buffett’s quote covered.

Right now, we have the opportunity to pay historically low P/E ratios even for high-quality companies that are growing fast. When companies can grow by taking market share, by expanding into new geographies, by raising prices, or because the industry they operate in is enjoying structural tailwinds, they don’t need the warmth of a growing economy to help them along.

There are many companies here and globally that are growing and aren’t sensitive to the vicissitudes of the economy. Of course, their share prices are sensitive and that is what provides the opportunity. Share prices have fallen because P/Es have contracted, reflecting sentiment. The underlying businesses however are stable. And one day P/Es will expand again. Investors will then receive the return from the growth of the earnings and the return from the expanding P/E.

Today it’s time to sharpen your pencils. Oh, and any further share price falls from here just strengthen the argument and boost future returns.