One more nail? Or is that it?

Former CEO, public speaker and author, Jay Grewal once said, “When it comes to the final nail in your coffin, it doesn’t matter if it’s dull or sharp, it’ll still hold, because a lifetime of prior nails have helped seal that coffin shut.”

In what may prove to be merely another accumulated nail in the coffin of the artificial intelligence (AI) boom, the narrative on Wall Street shifted dramatically last week as the tech-driven optimism that has fueled the market for years hit a psychological and structural barrier.

The question for investors is, does it represent a piece of yarn, which, if pulled, unwinds the entire market? Or will the market merrily quarantine stock losses in certain sectors?

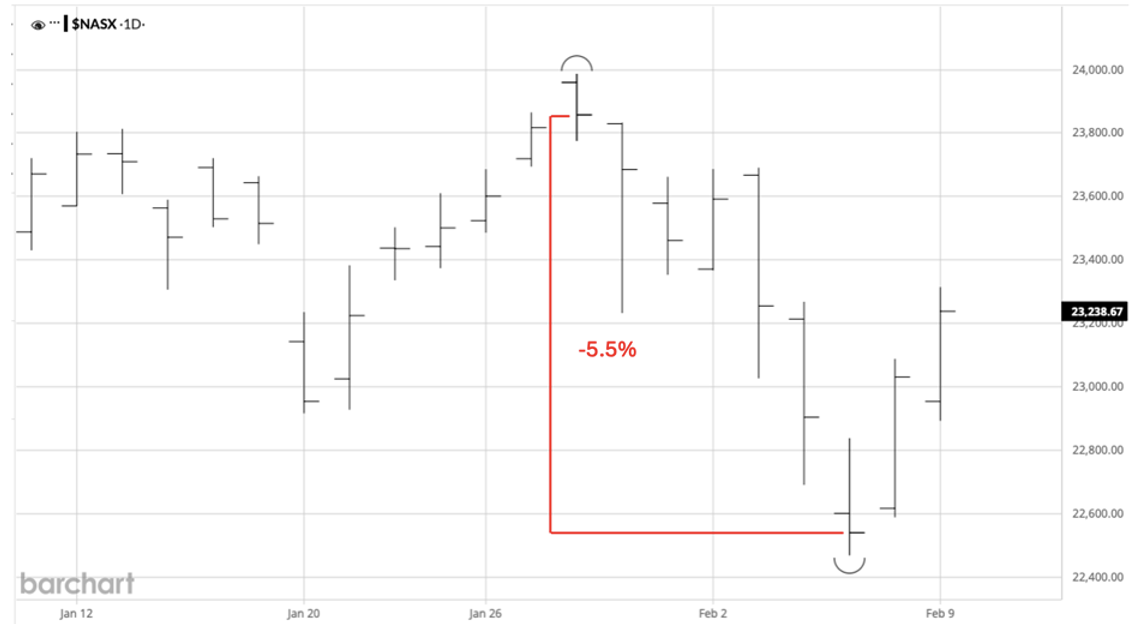

For much of the last decade, the Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) model was the gold standard for growth, but “SaaSpocalypse” sentiment emerged last week, forcing investors to question the very foundation of software value and pushing the Nasdaq 5.5 per cent below its recent all-time high (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Nasdaq. Daily, 1 Month.

Source: Barchart

The catalyst for the sudden identity crisis was the launch of Anthropic’s new Claude Cowork agent, a suite of plugins that transitions artificial intelligence from a passive advisor into an active assistant. Unlike traditional software that requires human interaction to manage workflows, these agentic tools can autonomously handle end-to-end tasks in data analysis, legal research, and marketing, leading many to fear that specialised software incumbents like Salesforce and Adobe, or Thomson Reuters and LexisNexis, will be rendered obsolete by in-house AI capable of doing the same work without the high subscription costs.

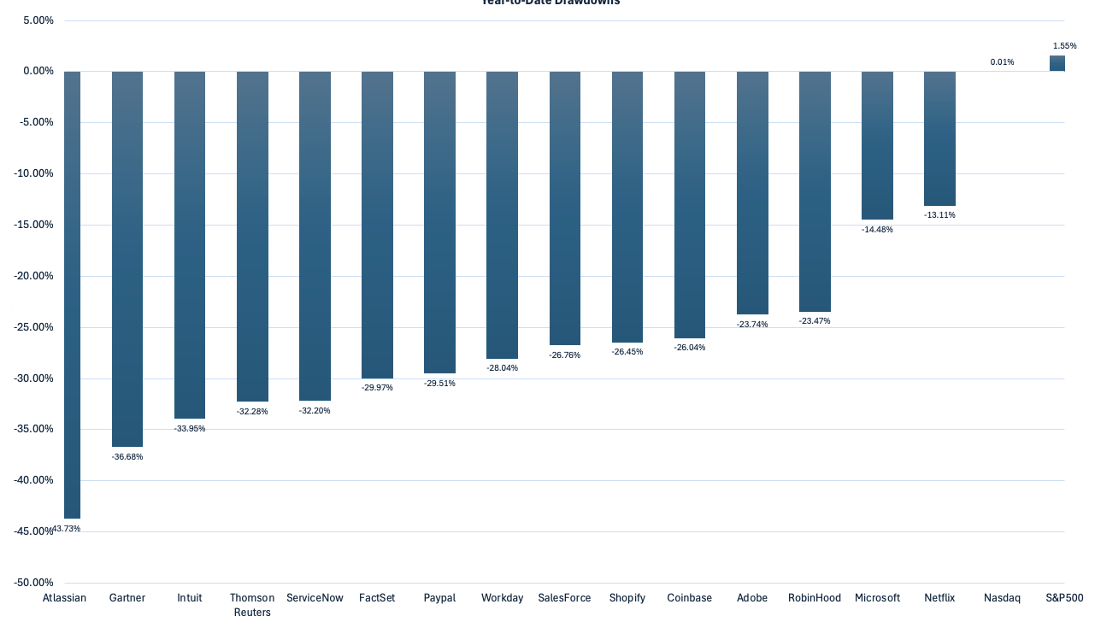

The big question that’s occupied my mind for some time is this: when the AI bubble bursts, will it take the rest of the market with it? It doesn’t have to. As Figure 2 reveals, there have been some spectacular stock price falls, and yet the NASDAQ and the S&P500 remain at or near their all-time highs.

Just because a single iceberg melts, doesn’t mean everyone on Earth has to leave the beach. In other words, losses can be quarantined to specific sectors of the market. While the software component of the S&P 500 has plummeted nearly 30 per cent from its record peak last October, the index itself remains remarkably resilient, closing, at the time of writing, near all-time highs (10th Feb 2026).

Figure 2. Year-to-Date Drawdowns

Source: X

If investors don’t want AI in their portfolios, they may not sell out of stocks entirely. Instead, they may rotate into other, less AI-exposed themes. That explains the long list of companies that have rallied significantly since the beginning of the year, such as Sandisk (+145.77 per cent), Western Digital (+66.01 per cent), Teradyne (+60.16 per cent), Seagate Technology (+54.33 per cent), and Intel (+36.15 per cent), among a long list of names.

And so, the localised tremor in AI and Software last week hasn’t brought the broader market to its knees.

Capital is not fleeing the market so much as it is migrating toward “real-world” sectors, including energy, materials, and consumer staples, which have taken up the baton from some tech names.

The pattern, however, has inspired a distinct sense of déjà vu for some of us who remember the early months of 2000. I had just begun building my first funds management company after leaving my role at Merrill Lynch when the tech bubble burst. The dot-com bubble, however, didn’t burst in a single day. After peaking in March 2000, the Nasdaq took more than two and a half years to trough.

More importantly, for our understanding today, as tech stocks, and the Nasdaq, began to slide in March 2000, healthcare and utilities rallied so strongly that the S&P 500 actually returned to within a percentage point of its record high six months later, and on a closing basis, peaked in August of that year.

A fish rots from the head, as they say. Through the act of ‘rotation’, a market can mask the deterioration of its most dominant sector for a surprisingly long time. One imagines, however, if the tech sell-off continues to deepen, the broader indices will eventually struggle to withstand the drag.

Many investors, however, quite rightly, point out that today’s market leaders are financially far stronger than the tech leaders of 1999, many of which were ‘pre-revenue’. It’s also worth noting that while the “AI bubble” may be the most discussed phenomenon in markets, the “Magnificent 7” (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, Nvidia, and Tesla) trade at an aggregate price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio of roughly 31 times. That’s high by historical standards, but it’s dragged up by Nvidia (37x) and Tesla (123x). And the Magnificent 7 P/Es are also supported by staggering levels of free cash flow, enviable returns on equity, dividends, and stock buybacks.

Unlike 1999, when exuberance was untethered from profitability, today’s tech leaders are still swimming in cash.

Of course, even the most profitable giants aren’t immune to occasional bouts of negative sentiment. That means they won’t be immune to emerging scepticism regarding the timeline for an AI payoff either.

Amazon’s recent earnings report is a case in point; despite strong AWS (Amazon Web Services) growth, the company’s plans to spend US$200 billion on AI infrastructure in 2026 – a figure that exceeded even the most aggressive Wall Street estimates – sent the stock tumbling as investors assumed deteriorating free cash flow required to fund this generational bet. A bet that may not pay off.

As is always the case in the maturing stages of general-purpose technology (GPT) booms, the debate now centres on whether this unprecedented capital expenditure will ever yield a reasonable return on investment or whether it will produce massive overcapacity.

JPMorgan Chase CEO, Jamie Dimon, offers an arguably self-serving middle ground, suggesting specific segments of the AI trade may indeed be in a bubble, but the overarching technology is a genuine “productivity revolution” similar to the early days of the internet.

As we have noted frequently over the last year, a general-purpose technology (GPT) will change the course of human history, but that doesn’t mean all investors win. From the automobile, to electricity, commercial flight, television, the telephone and the internet, history is replete with technologies that benefited consumers more than they benefited investors. You can watch our video on How General Purpose Technology booms end here.

Dimon also makes this point. He argues that mankind will ultimately benefit from AI, even if some investors lose money on overvalued individual stocks along the way. As the market continues to sort through this technological upheaval, the focus is shifting away from software subscriptions and toward companies that control the raw infrastructure and proprietary data that AI requires to function.

Whether this rotation marks a permanent shift back to the old economy and the market continues to rally, or whether it’s merely temporary and the rest of the market is dragged lower, remains to be seen. For now, at least, it seems safe to say the Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) industry’s long reign of unquestioned dollars-per-seat dominance appears to have ended.