Beyond the AI boom

As we farewell the shores of 2025 and sail into 2026, equity investors seem to be shrugging off fears of an artificial intelligence (AI) bubble and are instead betting on a growing U.S. economy, rate cuts, and a broadening of bullish sentiment beyond the AI leaders.

The consensus view is the U.S. economy is settling into a rate of growth that is more modest than last year’s, avoids a recession and could surprise to the upside. Meanwhile, U.S. inflation and employment data are generally seen as supportive of a Federal Reserve rate cut, even though, according to some economists such as Torsten Slock, two-thirds of inflation seems to be demand-driven.

Over the course of the year, the jobs market has weakened. The latest ADP jobs report revealed that private employers cut 32,000 jobs, more than expected.

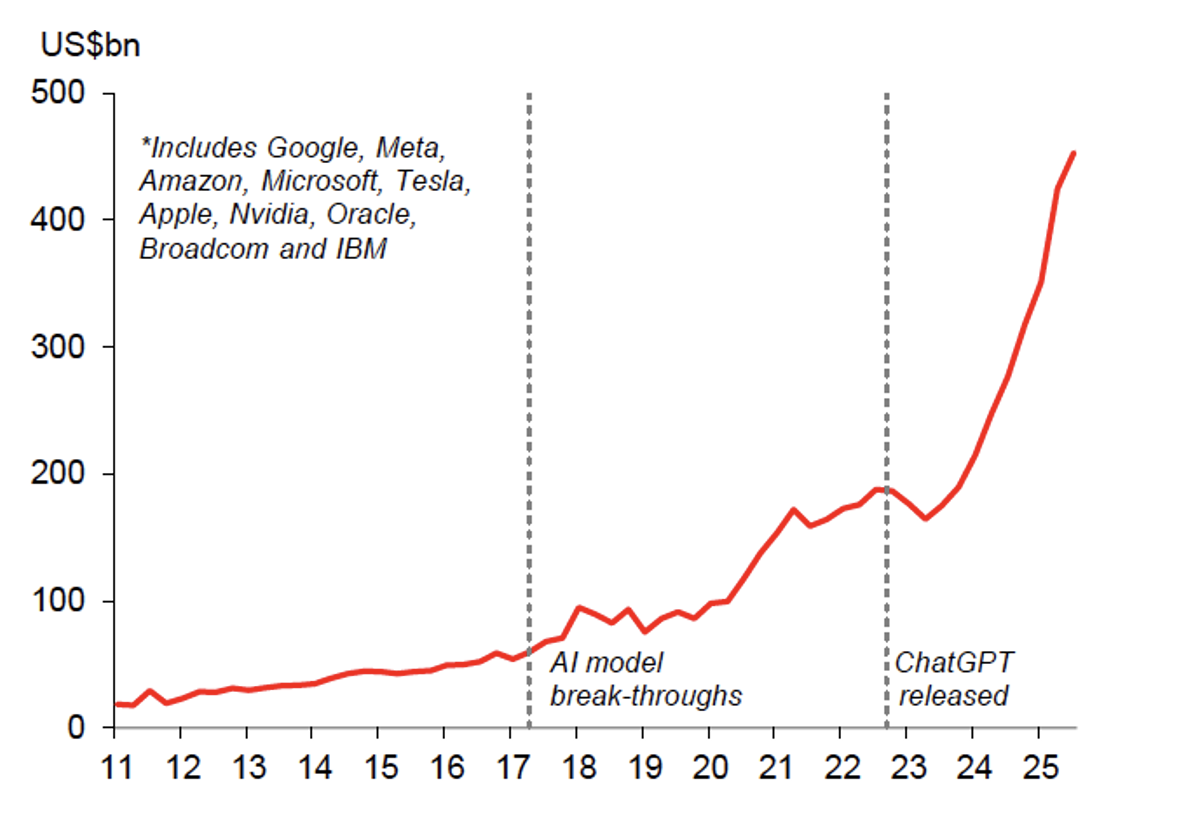

Other bullish drivers for the U.S. market include almost A$1 trillion of capital spending by AI technology companies, the end of Quantitative Tapering (QT), income tax cuts, massive budget deficit spending, US$2,000 stimulus checks and the forecast of a historically high volume (US$1.2 trillion) of share repurchases, suggesting U.S. corporations anticipate having a large amount of excess cash to support the U.S. stock market throughout 2026.

Figure 1. Capex of Top 10 Spenders as a share of 2000 largest U.S. equities,31 August

Source: Trivariate

Recently, Fortune Magazine reported, “U.S. GDP growth in the first half of 2025 was almost entirely driven by investment in data centres and information processing technology, according to Harvard economist Jason Furman. Excluding these technology-related categories, Furman calculated that GDP growth would have been just 0.1 per cent on an annualised basis, a near standstill.” And while that underscores the increasingly pivotal role of high-tech infrastructure in driving economic growth, the sluggishness in non-artificial intelligence (AI) sectors supports the rate-cut narrative.

Figure 2. Big Tech Capital expenditure (capex), seasonally adjusted, quarterly annualised

Source: Bloomberg, BEA, Macrobond, Macquarie

More importantly, perhaps, is the idea that technology can have a big impact on productivity, but it has always taken longer than the promoters would like. And while the U.S. will probably lead adoption, Europe will regulate it’s way to adoption and therefore adopt it more slowly.

The prevailing forecast for U.S. Real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth for 2025 is between 1.8 per cent and 2.0 per cent, a slowdown from the 2.4 per cent to 2.8 per cent growth rates seen in 2024. The decline is partly due to weakness in the most recent quarter, stemming from the federal government shutdown and delayed spending.

Looking ahead, the consensus for 2026 is annual growth hovering around 1.8 per cent to 2.0 per cent. However, some economists, like Macquarie Bank’s Rick Deverell, believe U.S. 2026 growth could surprise to the upside. Notably, those that are more bullish, cite sustained AI-related investment and delayed effects of prior fiscal stimulus contributing to above-consensus growth expectations of around 2.4 per cent (Q4/Q4).

Employment

Forecasters describe the employment picture as a “low-hire, low-fire” environment, where job creation has slowed but widespread layoffs are largely being avoided, contributing to economic stability.

Unemployment rate

Consensus projects the annual average unemployment rate for 2025 to be around 4.2 per cent, with a slight increase to 4.4 per cent to 4.5 per cent expected in 2026. This level of unemployment, while higher than the recent cycle lows, is still historically low and suggests that the labour market remains relatively tight.

Payrolls

Monthly nonfarm payroll gains are projected to continue decelerating. The average monthly job growth for 2025 is expected to be around 125,100, slowing further to approximately 55,200 per month in 2026. The slowdown suggests the Federal Reserve’s restrictive monetary policy is having its intended effect.

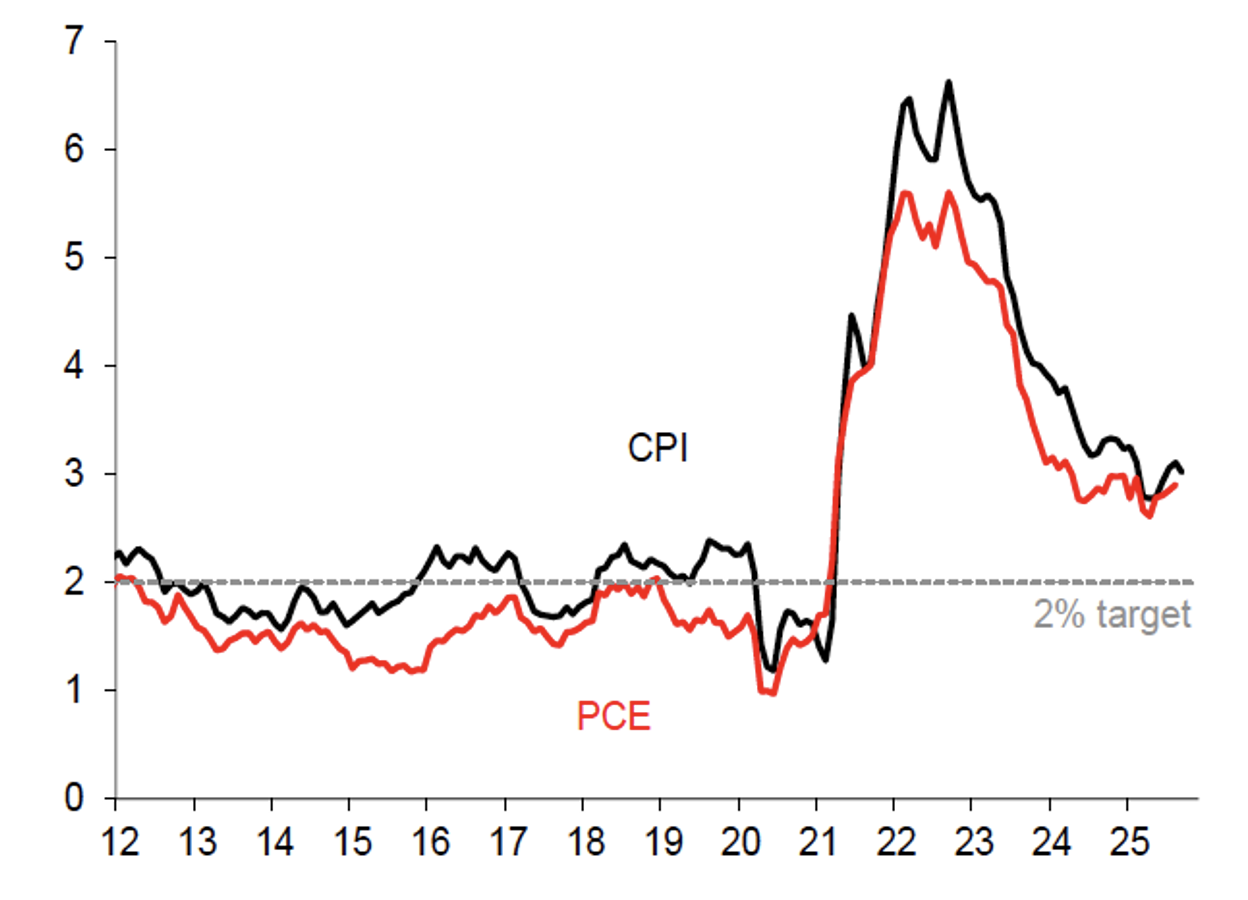

Inflation

Inflation remains the most significant point of friction in the economic outlook, remaining above the Federal Reserve’s 2 per cent target. The persistence of elevated prices dictates the uncertainty surrounding monetary policy.

Figure 3. U.S. core inflation, year-ended (%)

Source: BEA, US Customs & Border Protection, Macrobond, Macquarie

That said, market participants, including Goldman Sachs, J.P. Morgan, and Bank of America, are reporting that the U.S. Federal Reserve has told them a December rate cut is on the way. This move is viewed as an “insurance cut” against downside risks to employment, but forecasters are cautious, noting that further cuts are not automatic given elevated inflation and the likely positive impacts of the Big Beautiful Bill, the end of Quantitative Tightening (QT), and tax cuts.

The overall expectation is for a slow, data-dependent easing over the next year, and possibly rate hikes in 2027.

Both headline and core CPI/PCE inflation are expected to remain elevated, with year-over-year figures persisting near 3.0 per cent through the end of 2025 and into the first half of 2026 before easing toward 2 per cent later in the year. The slow disinflation in the services sector and upward pressure from tariffs and goods prices contribute to this persistence.

Summary

The consensus view is that the U.S. economy is successfully navigating a narrow path toward a soft landing, a growth rate near 2 per cent and a tight labour market.

Arguably, the big surprise this year is not that a recession was avoided, but that the AI boom hasn’t yet delivered meaningful productivity improvements.

The delay to those improvements has shifted expectations for the massive technological investments to translate into the productivity gains necessary to sustain growth, offset inflation, and allow the Federal Reserve to normalise interest rates by 2026.

Hi Roger,

Excellent & accurate reporting in capturing the consensus that the U.S. economy is on a narrow soft-landing path, with modest growth, sticky inflation, and a tight labour market. Your emphasis on AI investment as both a driver and a risk is well-founded. I hope your optimism in assuming fiscal stimulus and buybacks will meaningfully sustain growth. I think that AI is propping up GDP now, but productivity gains, and true inflation relief, remain a 2026–2027 story. This dynamic reflects a familiar pattern: transformative technologies initially inflate growth figures through capital expenditure, but the tangible productivity benefits take years to materialize.

On a more sobering note, Stuart Russell’s recent interview with DIARY OF A CEO on 4/12/25 underscores the other side of this story. While economists focus on AI’s role in sustaining growth, Russell warns of the existential risks tied to unchecked development of artificial general intelligence. He highlights the lack of robust safety measures, the departure of AI safety staff from leading firms, and the possibility of a “fast takeoff” where systems train themselves beyond human control. His reflections, ranging from the erosion of middle-class jobs to the philosophical question of whether we are creating our own successor, add a sobering counterpoint to the economic optimism. Taken together, the economic consensus and Russell’s caution suggest that AI is simultaneously the engine of near-term growth and a long-term uncertainty. I suspect we won’t have to wait too long to reveal whether this AI boom delivers productivity gains or deeper societal risks.

Regards, Joe

Hi Joe, I read your comment with interest and then realised it was AI-generated. Sentences like “This dynamic reflects a familiar pattern: transformative technologies initially inflate growth figures through capital expenditure, but the tangible productivity benefits take years to materialize” are a give-away. In Australia, we write ‘materialise’ not ‘materialize’, also a give-away. “Underscore” is classic Grok and ChatGPT too. Thanks for your AI’s comment.