Why growing household debt makes us concerned

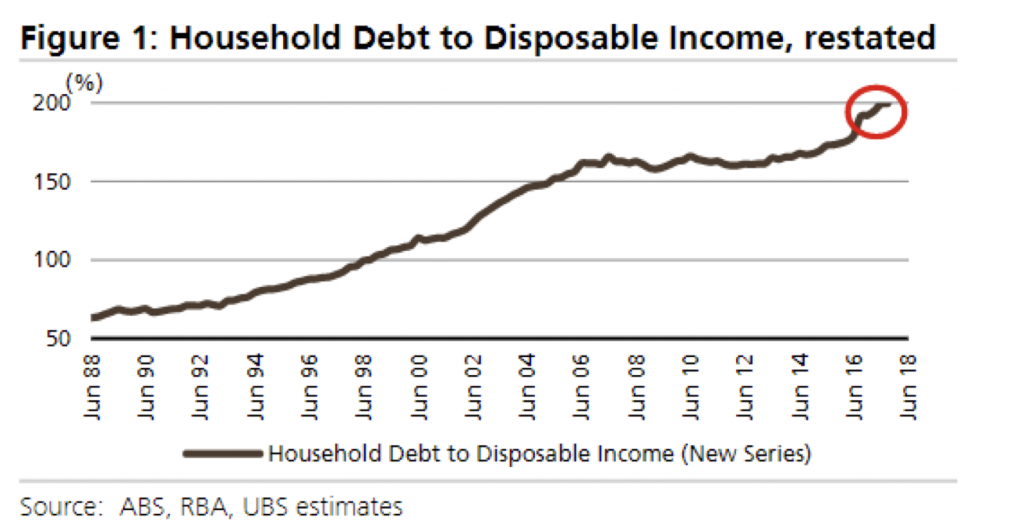

Latest figures show Australia’s household debt and gearing keep on rising, with the ratio of household debt to disposable income now at record levels. The recent rise has been largely due to the loan book growth of smaller institutions and non-traditional lenders, often to higher-risk borrowers. This is a worrying development.

Over the last few years, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) and the Reserve Bank (RBA) have voiced concerns over lending practices and the potential for continued growth in household debt to threaten the stability of the economy and financial system. In response, APRA has implemented a range of macro-prudential restrictions on lending in segments of heighted concern.

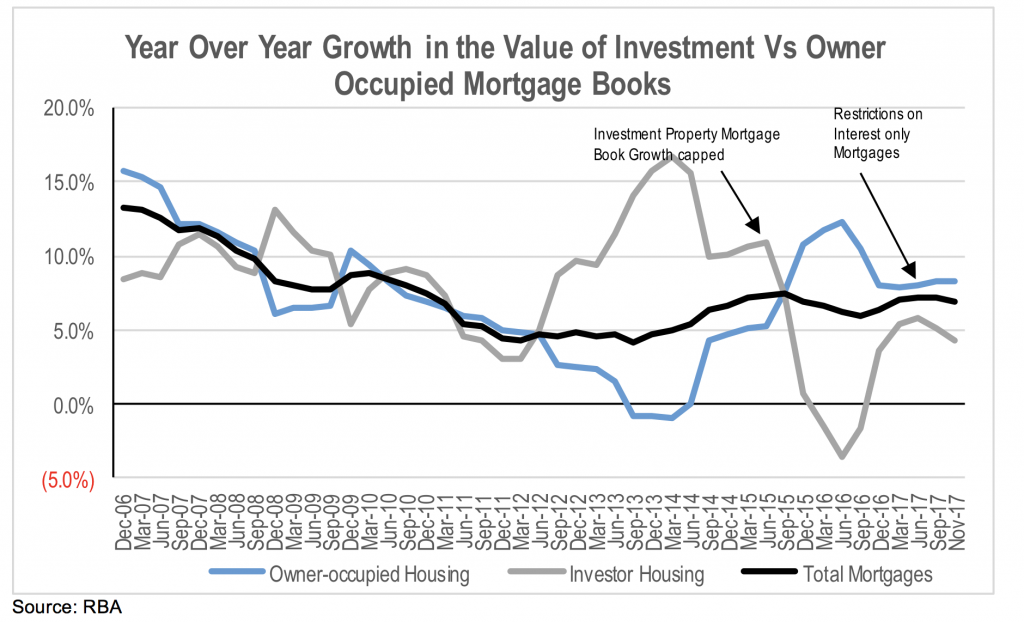

The most notable of these restrictions were the 10 per cent on bank investment property mortgage book growth, and the 30 per cent cap on the proportion of new mortgages with interest-only repayments rather than principle and interest. Despite the introduction of these restrictions, the rate of growth in aggregate mortgage books across the Australian system has remained stable at around 7-8 per cent over the last 3 years according to RBA data.

If we look at aggregate measures of household debt in Australia and the level of household financial gearing through the debt to disposable income ratio, household debt and gearing has continued to rise unabated.

At the same time, the recent bank results and commentary have pointed to slowing loan book growth and more competition. So where is the disconnect?

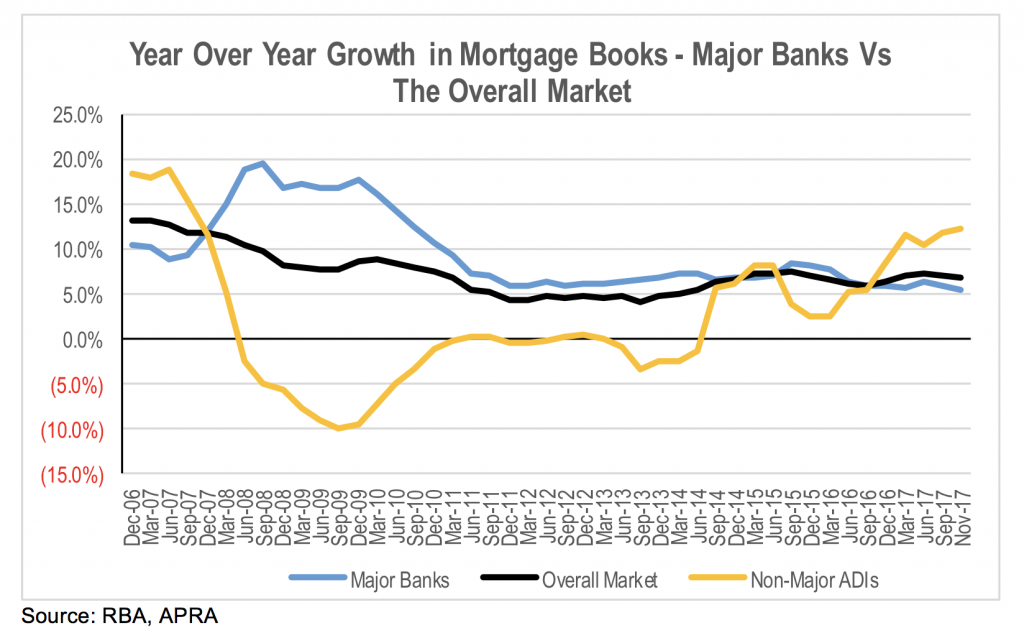

If we look at the rate of growth in the mortgage books of the four major banks, we can see that it has slowed from around 8 per cent at the end of 2015 to 5.5 per cent at the end of 2017. While this is not a material slowdown in the rate of growth, it is notable that investment property loan book growth has slowed to 3.5 per cent, so it appears the targeted restrictions implemented by APRA have had an impact on major bank lending to some degree.

Where there has been an even more pronounced slowdown is with the regionals (BEN, BOQ, SUN) and Macquarie Bank. Year-on-year mortgage book growth for these four banks has slowed from above 10 per cent in 2015 to just 2 at the end of November 2017 according to APRA data, with all four of these institutions showing low single digits loan book growth.

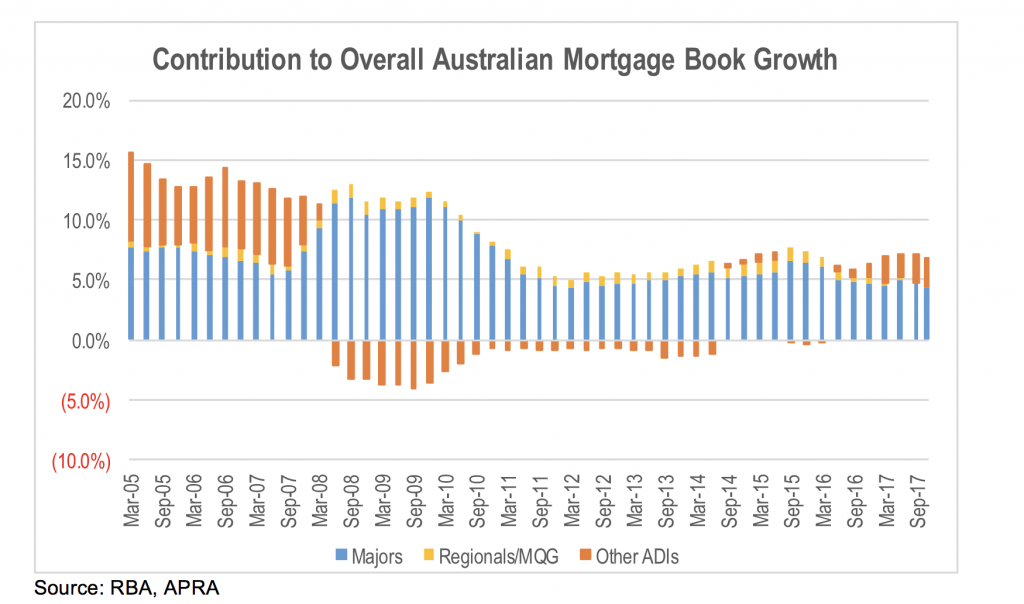

Offsetting slowing loan book growth for these institutions has been a significant acceleration in growth for smaller Approved Deposit Institutions (ADIs) and non-traditional lenders.

Mortgage books for smaller ADIs and non-traditional lenders were shrinking in aggregate following the GFC right through to mid 2014. However, since the end of 2015, these lenders have seen a significant acceleration in their rate of mortgage book growth such that they are taking share from the larger banks. In fact, at the end of 2017, the small lenders were contributing over a third of the growth in the overall market.

The contraction in small lenders loan books post the GFC is likely to have mainly been a function of a squeeze on their access to wholesale funding. Aggressively accommodative monetary policy from developed market central banks has since seen the cost of funds fall and its accessibility increase. At the same time, a gradual increase in regulatory restrictions and requirements on the Australian banks has resulted in increasing lending rates, particularly on investment property and interest-only mortgages. The combination of increased availability of wholesale funding and upward pressure on mortgage rates relative to benchmarks has opened the door for smaller lenders.

However, the RBA data presented above does not show the whole story. Non-Approved Deposit Institutions (non-ADIs) have also become more competitive recently. These ‘shadow banks’ can target products in which the major banks have lifted rates due to regulatory concerns about growing risks. Canstar estimates that non-ADIs are offering rates that reduce monthly repayments by around 10-15 per cent for borrows relative to a similar product from an ADI. The RBA data used above only includes some of the non-ADIs lending into the mortgage market.

The big question is whether this surge in lending by smaller players is being focused on higher risk borrowers that are being turned away by the larger banks? This would severely limit the effectiveness of APRA’s macro-prudential policies in reducing the financial risks that are building in the residential mortgage market.

There has been some evidence of a deterioration in lending practices. Surveys undertaken by UBS of new mortgage borrowers last year highlight potential issues with the accuracy of mortgage applications. Additionally, there is a risk that a significant proportion of consumers that have interest-only loans are not aware that they face a significant increase in their monthly repayments once the interest-only period expires.

More recent actions by APRA also indicate that it is concerned about potential slippage in lending practices. APRA increased its scrutiny of living expense estimates on applications to provide a more realistic impression of serviceability of the mortgage. It was also granted powers to capture data from non-ADIs due to concerns that ADIs that are constrained due to regulatory limitations are providing funding to non-ADIs that provide mortgages to riskier borrowers.

APRA appears to be engaged in a game of ‘whack-a-mole’ in targeting particular areas of concern. The problem is that while it holds a mallet, other government policy setters are busily feeding the moles with steroids in the form of loose monetary conditions.

Latest figures show Australia’s household debt and gearing keep on rising, with the ratio of household debt to disposable income now at record levels. Stuart discusses what this means for the economy. Share on XThis post was contributed by a representative of Montgomery Investment Management Pty Limited (AFSL No. 354564). The principal purpose of this post is to provide factual information and not provide financial product advice. Additionally, the information provided is not intended to provide any recommendation or opinion about any financial product. Any commentary and statements of opinion however may contain general advice only that is prepared without taking into account your personal objectives, financial circumstances or needs. Because of this, before acting on any of the information provided, you should always consider its appropriateness in light of your personal objectives, financial circumstances and needs and should consider seeking independent advice from a financial advisor if necessary before making any decisions. This post specifically excludes personal advice.

INVEST WITH MONTGOMERY

In relation to the volume of IO mortgages, and knowing that refinancing to P&I is inevitable for a proportion of these mortgages, with resulting increase in repayments, it would be interesting to see the projected trend of when these changes in refinancing will occur. This will give insights into when an increase in mortgage stress can be expected, hence, when the property supply side may increase!!

Don’t worry. The great Glen Stevens and now Phillip Lowe have been looking at this problem with a very concerned furrowed brow. Shame they refuse to admit that these theatrics don’t actually solve the problem. So of course the problem builds as they continue to passively monitor the situation as it gets worse and worse.

I can only imagine that record levels of private debt means a crash is baked into the Oz economy. The only question is what will set it off? A China slowdown and/or sharply higher interest rates would be my guess. Or maybe if RE prices continue to fall the bubble will be pricked even in the absence of these catalysts. In the meantime I’ll have to watch through gritted teeth as the majority of fund managers predict a bull market ahead (Monty Funds excluded) while riding the gravy train singing the mantra of ‘global co-ordinated growth’.

There won’t need to be a trigger to set this off, other than basic mathematics associated with debt saturation. I’ve lost count of the number of families I know who are regularly refinancing their home to free up equity for consumption. As time goes by they are finding it more difficult to find banks who will approve them – they’re now reliant on mortgage brokers to ‘get them over the line’. They’re borrowing more with practically zero income growth and entirely reliant on increasing valuations on their property. As soon as that growth moderates they are finished. Retail will be smashed.

Much of the data coming out of the ABS seems to be ‘ex-refi’. Wouldn’t it be interesting to see what proportion of the Australian mortgage book is refinanced on an annual basis? I think we’d be staggered at the growth in that number.

I would think the level of mortgage book refinancing (if I’m understanding you correctly) is implicit in the above ‘household debt to income chart’, and that sure is staggering.

I have to wonder how those families you mention are going now that the equity in their homes has now started to decrease.

Apart from retail getting smashed I think construction workers, not to mention all the other jobs supporting the RE industry, will also take a hammering. Last time I checked, construction was over 10% of our GDP. Other developed countries tended to be around 5%. Construction employs a million people alone. What if that halves?