What are some of the risks with big bank shares?

Recently we received a question in writing from one of our investors expressing concern about bank shares in which Montgomery Funds have recently acquired some exposure. Stuart Jackson devoted a little time to answer so we share it with you here.

As you will be aware, we have been cautious on the banks for a while given concerns over changes to capital requirements, the implications for the relative competitive position of the majors, what that means for sustainable ROE, and how that feeds into valuation for a group of stocks that were at best fully valued.

Over the last couple of months we have increased our exposure slightly given an improved risk/return outlook resulting from more favourable share prices.

In terms of the concerns raised by the reports you have attached, there are a number of commonalities with our thinking, albeit on a less alarmist basis. This forms part of our overlay in terms of risk.

While investors in Australia could be accused of having been lulled into a false sense of security when it comes to the banks in viewing them as defensives, this is largely due to the fact that the Australian economy hasn’t experienced a recession for 24 years. Banks are actually leveraged plays on asset values.

The points made in the article are similar to a lot of overseas analysis of the Australian banks that has been around for the last 10 years. This of course does not mean it can be disregarded, but there are some aspects of the argument that don’t take into account some of the fundamental differences between the way the Australian market operates relative to that of the US.

Exposure to Residential mortgages

The skewing of the loan books within the banks toward mortgages over the last 25 years is a function of a few factors. First, it reflects changes to regulatory risk weightings. This has become more significant over the last 5 years with the introduction of internal risk modelling. Another factor has been the increasing use of syndicated and offshore borrowing combined with FX swaps for corporate lending. The other factor is that Australian banks keep a much higher proportion of mortgages on balance sheet than overseas banks due to the small size of the securitisation market. This overstates the differences in loan book mix to some extent.

Household Debt Levels

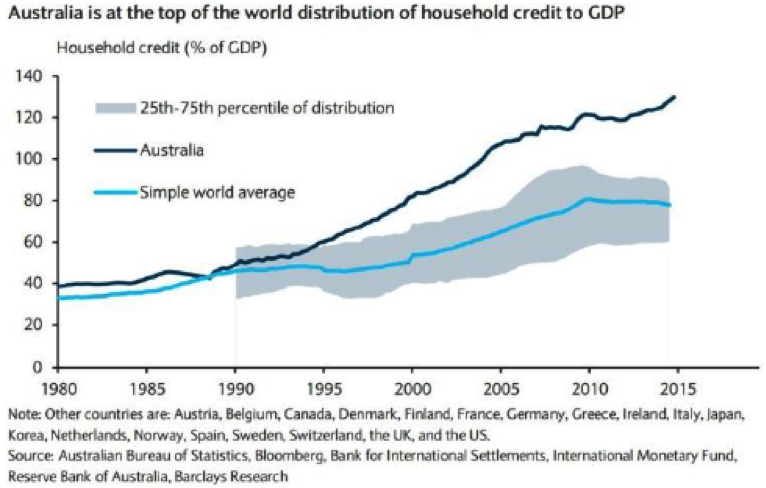

In terms of household debt as a % of GDP, this is definitely an issue. As the chart below shows, debt levels in Australia have increased as a % of GDP over the last 3 years, whereas they have generally declined in other developed countries.

Source: Variant Partners

It should be recognised than the sustainable level of debt is a function of the cost of that debt. Interest rates remained higher in Australia post the GFC than in other developed countries like the US and Europe, which moved quickly to adopt zero interest rate monetary policies. Australia has only begun cutting rates to record lows in the last 2 years. This is likely to have stimulated debt drawdown at a household level.

The other point I would make is that from a broader economic standpoint, relatively high household debt levels in Australia are offset by relatively low Government debt levels. This provides more balance and allows for greater government response to any downturn.

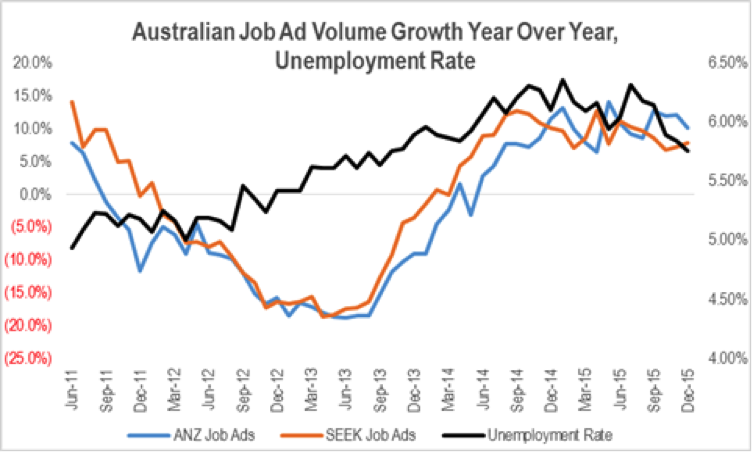

For high household debt to become an issue, there needs to be a trigger to cause an affordability problem. This can come from either an increase in interest rates or a spike in unemployment. The later was clearly an issue that has seen household debt levels reduced in other developed markets. However, while unemployment increased in late CY14 and early CY15, it appears to have stabilised.

The risk of spike in the unemployment rate has moderated in recent months as activity in the economic has rotated more quickly than expected from business investment in new mine development toward more services oriented industries like tourism and education. While mining became a big driver of GDP growth as a result of the rising terms of trade, the benefits of the boom fed a very narrow portion of the overall population base despite Government efforts to redistribute the benefit more broadly through increases in middle class welfare.

At the same time, the rising AUD choked industries that support a much larger proportion of the population either through uncompetitive exports or increased import competition. My contact with consumer companies has indicates that markets like western Sydney and SE Melbourne were in recession between 2009 and 2014.

The collapse in mining investment has resulted in weak GDP through lower aggregate business investment and income generated by mining related companies. Business investment has been slow to rotate from mining toward other industries post the boom. However, sales and demand for services industries has been much quicker to react. While mining activity is a big delta for GDP growth, it is still a relatively small part of the overall economy. The Australian economy is far more services based, and demand has rebounded in the broader base of the economy more quickly than expected on the back of the stimulation of residential construction through lower interest rates, as increased international competitiveness resulting from the lower AUD.

As such, while we see household debt as a concern, the risks associated with this have diminished to some extent in the last 6 months with the improvement in employment market conditions. However, we continue to monitor employment conditions as a key indicator of default risk.

Source: ABS, SEEK, ANZ

In order to see property prices collapse you need forced sellers. This is key to looking at risk to the mortgage book.

A key point of difference between the US mortgage market and Australia is that in the US, mortgages are largely non-recourse. As a result, if the value of a home falls below the value of the mortgage, the borrower can hand the keys back to the bank and the bank cannot tap any of the borrower’s asset to make up any shortfall in the principle. This effectively see the banks having sold a call option over properties to the borrower at a strike price equal to the value of the principle.

This means that falling house prices tend to build increasing downward pressure on house prices as lower prices result in an increased number of people with negative equity and increased short sales by the banks.

In Australia, the banks have access to the borrowers other assets. As a result, just because the value of housing falls such that a borrower has negative equity, it does not mean they will default on the loan. Default in Australia only comes about if a borrower is no longer able to make the repayments. This is more of a function of the unemployment rate, or a rise in interest rates. As previous noted, the latter is very unlikely for the foreseeable future.

In the US, borrowers handing back the keys to the bank once they have negative equity creates a forced seller in the banks. In Australia, you would need default due to a spike in unemployment. As discussed earlier, we believe the outlook for employment markets in the broader economy have improved to some degree over the last 6 months.

The fundamentals of the Australian housing market remain positive with relatively strong population growth (albeit it has moderated recently), international capital inflows, and a shortage of housing stock given 120,000 new housing starts a year for number of years compared to average new household formation of around 160,000 a year. This doesn’t mean expect house prices to continue to rise, but demand fundamentals reduce the risk of a significant fall.

Economic growth is strongest in Sydney and Melbourne. As such it is not surprising that housing prices have been strongest there. This should continue to be the case given those cities are relatively more exposed to services and currency exposed industries.

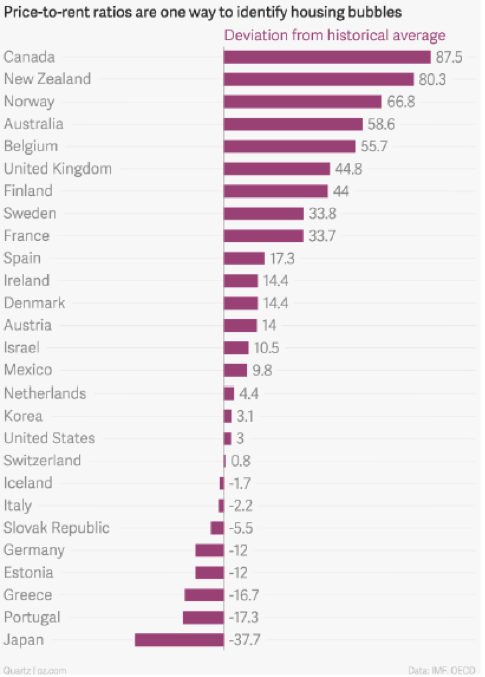

In residential property yields around the world shown in the chart below, these are distorted by differences in property costs such as taxes and other operating costs.

Source: Variant Partners

The comparisons generally quote gross yields rather than net yields. In the US, property taxes are very high (eg in New York, annual taxes on a standard 2 bedroom apartment in Manhattan are around US$15k a year). The costs of owning property are incorporated in the gross yield. The cost of owning property in Australia is considerably lower than in other parts of the world reducing gross yields by around 2-3 per cent relative to some countries.

The gross yield in Australia has fallen over the last few years as a result of lower interest rates. This is part of the broader duration trade that has driven asset prices globally over the last 30 years.

Asian Lending Risks

On exposure to Asia, this was a key concern (among others) that led us to exist our position in ANZ in August last year. This remains a concern. However we note that the new CEO Shayne Elliot flagged a change in strategy regarding Asia at the result in November. He will look to rationalise the business, dumping low margin and return customers in order to lift returns in the business. This moves away from Mike Smith’s strategy of cross subsidisation of short term lending products to get transactional business. Mike Smith knew it did not have the incumbent relationships, network or low cost position due to scale in the Asian markets. As a result, he needed to use price to get relationships in the hope they could use that to sell more profitable and high return products over time. The problem this creates from a valuation basis is that it was continually diluting ROE (and adding risk). Asia generates an ROE of 8% vs 15% for the Aust/NZ business. Given Asia was growing faster than Aust/NZ, it was absorbing a much high proportional of capital on a margin basis than the proportions implied by the historical ROE for the group. This means that using the current level of ROE as a guide to sustainable marginal ROE for valuation overstated the value of ANZ. The reality is that with the business and capital mix shifting toward Asia over time, the marginal ROE (which should be used for valuation) was considerably lower than the current average.

Shayne’s comments signal that he doesn’t have the patience for Mike Smith’s long term strategy. This is why we forecast the Asian loan book to shrink by 20 per cent over the next couple of years, but Asia lending margins improving as an offset. By pulling back on Asia, and improving its returns, the outlook for marginal return in the valuation improves. Offsetting this, the outlook for earnings growth declines. Additionally, risk (and the cost of capital) should also decline. I would suggest the net of these factors is marginally positive for valuation.

Low Loan Loss Provisioning

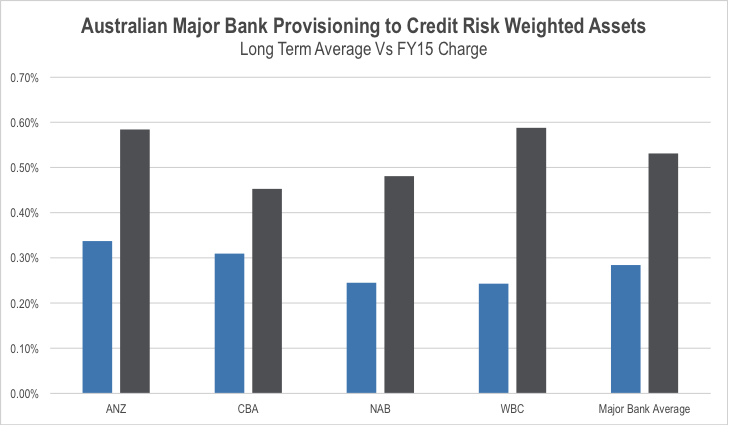

On provisioning, we share your concerns that most of the earnings growth generated by the major banks over the last 4 years has been the result of falling provision charges as the banks wrote back the provisions taken after the GFC. Provisions are currently well below long term averages. This is why when valuing the banks, we adjust the earnings base to reflect a long term average level of provisions.

If you look at provision charges over the last 30 years as a percentage of credit risk weighted assets, it has averaged around 50bpts on a fairly consistent basis across each bank. This is the level we base our valuation on in projecting sustainable earnings.

Source: JPMorgan

While this approach won’t protect the investment significantly if there is a major asset price deflation cycle, it reduces the risk of overvaluing the companies and being exposed to a normalisation of earnings to more sustainable levels in future.

Sustainable Dividend Payout Ratios

Undoubtedly, the benefits of the 30 year duration trade are coming to an end. Therefore the rate of loan book growth is set to slow in coming years as debt levels stabilise as a % of GDP. This is main reason why we believe that dividend payout ratios can probably be sustained by the major banks. Slower loan book growth requires lower earnings to the retained, offsetting the impact of higher capital requirements and lower marginal ROEs.

So in summary, we increased our exposure to the banks recently because:

- We perceive there to be a little less risk a significant fall in asset prices given the improving employment market from the more rapid rotation in economic activity toward services industries which provide a more broad benefit to the population.

- The risks in Asia remain an issue, particularly for ANZ, but a change in strategy should lessen the risks. Having said this, asset price risks and high household debt levels mean we demand a higher cost of capital and a larger discount to valuation to own the banks than previously.

The fall in bank share prices resulted in the risk/return on the stocks to improve to warrant an increased exposure. However, I would note that we remain less exposed than the broader market due to our ongoing caution regarding the risks discussed.

Stuart Jackson is a Senior Analyst with Montgomery Investment Management. To invest with Montgomery domestically and globally, find out more.

This post was contributed by a representative of Montgomery Investment Management Pty Limited (AFSL No. 354564). The principal purpose of this post is to provide factual information and not provide financial product advice. Additionally, the information provided is not intended to provide any recommendation or opinion about any financial product. Any commentary and statements of opinion however may contain general advice only that is prepared without taking into account your personal objectives, financial circumstances or needs. Because of this, before acting on any of the information provided, you should always consider its appropriateness in light of your personal objectives, financial circumstances and needs and should consider seeking independent advice from a financial advisor if necessary before making any decisions. This post specifically excludes personal advice.

INVEST WITH MONTGOMERY

The increased capital requirements was said to provide advantage to the smaller banks [Bendigo, BOQ] vs the big 4. Is this proving to be the case, or do small banks suffer from the same general environment as the big4

Hi John,

As you note, changes to regulations should address some of the competitive disadvantages impacting the regional vs major banks. In July, APRA announced that the minimum risk weight that can be applied by the bank using internal risk modelling will increase to 25%. This will see the amount of core tier 1 equity capital the major banks (and MQG) will need to hold against mortgages increase by around 60%, resulting in lower ROEs. As the regional banks have not been accredited to run their own internal risk models, they need to use standardised risk weights, resulting in significantly higher capital requirements for mortgages than the major banks and therefore lower ROEs at the same level of profitability. While the changes from 1 July will narrow the gap in terms of capital requirements, it will not completely eliminate it. For example, BEN operates with an average mortgage risk weight of around 40%, and BOQ is slightly higher than that. The other area of regulation that will see the competitive advantage of the major banks narrowed is in terms of increased capital and liquidity requirements to ensure that they are “unquestionably strong”. APRA’s final definition of “unquestionably strong” remains a matter of speculation, but the banks will be required to hold more capital overall than the regionals, as well as greater liquidity in future.

While these changes will see the competitive advantage of the major banks narrow relative to the recent history, they will still enjoy the benefits of scale through lower cost to income ratios and better funding access.

The improved competitive position of the regionals could be utilised in one of two ways. The regionals could look to reinvest the benefits in improving their price competitiveness. With the major banks lifting mortgage rates to offset the impact of higher capital requirements on ROE, the regionals could take to opportunity to become more price competitive by not following, and therefore gain volume share. Alternatively, they could follow the majors in lifting pricing, thereby increasing their margins and ROE. The anecdotal evidence so far indicates that BEN has focused more on improving margins and ROE, while BOQ has been more aggressive in pursuing market share through front book discounting. There is evidence of increased discounting of owner occupied mortgage packages at other smaller banks as well. We can see from the most recent APRA data that BOQ is gaining share in mortgages while BEN is losing share.

Hi Stuart, great analysis there. I think if Montgomery is having to allocate funds to banks with their equivocal and debatable short-medium term prospects there must not be much value in the market right now! It doesn’t appear to be an easy decision to invest in banks now given how you have traded in and out of them in such a short space of time. I am out of banks now anyway. If we look at one long-term theme being the ageing and retiring population, these people are mostly going to aim be debt free, so will be a significant headwind for loan growth I feel. And regulatory hurdles make borrowing hurdles for owner-occupiers and investors much harder, whether through LVR restrictions or serviceability criteria. Asian business for ANZ and other banks is not the saviour some have tried to convince us it was. So that leaves business lending, margin expansion and cost reduction to drive returns going forward. Hard to say if that will be enough with increased fintech competition. And even if one or two of the weaker banks cut dividends, retail investors may head for the hills on the whole sector with the bearish commentary that follows. Certainly to me they are not as compelling as they have been in the past. But maybe that slightly uncomfortable feeling you have with banks here is what you need to be contrarian!

Do you think the introduction of blockchain technology being tested by some of the major Australian banks will cut costs in a significant way? It has been reported this leading to potential upside via cost reduction? I was wondering you point of view?

http://blogs.wsj.com/cio/2016/02/02/cio-explainer-what-is-blockchain/

Hi Sally,

Blockchain technology is one of a number of technologies that offers the potential to significantly reduce the financial services costs and improve inefficiencies. This technology would allow banks to significantly reduce middle office costs associated with processing and settling transactions while also reducing the frequency of errors and settlement periods. It represents both an opportunity and a threat to the major banks in that adoption of the technology would dramatically reduce costs, but it would take time, and significant restructuring of the business to implement. At the same time, it could reduce the scale benefits of the major banks, allowing new entrants to compete in the market. A new entrant would start with a more efficient operating structure that is built with around the new technology. The incumbents will need to change which will take time and require significant cultural change. As a number of press articles are highlighting, some of the major global banks (including CBA) have built working blockchain ledgers to demonstrate how they work to regulators. It will be up to the regulators to assess the implications of de-centralised ledger systems on the stability of the financial system. But it appears that there could be wide ranging applications for blockchain technology in financial services that could result in dramatic changes in industry costs and efficiency.

Hi guys,

Looking at the big 4 banks and NAB’s pending demerger of CYBG do you have any thoughts on this new entity? Will in the short term have some legacy issues to sort out.

To me it looks similar to the demerger of Henderson from AMP all these years ago and Henderson has moved forward in leaps and bounds since.

Thanks for taking the time to read my question.

Clydesdale and Yorkshire Bank (CYBG) however is not a funds management pure play though.

Thanks Roger, I was wondering if CYBG has the great business characteristics or is it too early to know this and they need runs on the board first.

it would need to improve its competitive position significantly to be classified as a great business.

There have been a number of de-mergers in recent years. The main thrust of the bull case for CYBG is that now it has been released from the bureaucracy of NAB, it will be free to invest directly in its business and set its own objectives. As a standalone entity, it will be more focused and it will be better able to incentivise its management and staff to improve its operations. CYBG believes that it will be able to reduce its operating costs over the next few years as it benefits from new systems investment recently undertaken. It is targeting a 40% increase in the size of its loan book over the same period through the use of the broking channel and expansion of its exposure to non-traditional geographic markets for its products (ie primarily SE England). The company expects loan book growth, combined with some improvement in net interest margin from the run off of some low margin legacy business and an eventual increase in interest rates by the Bank of England (which is looking like an even longer term story at present), combined with fixed cost leverage to increase the bank’s ROTE from 5% at present toward its target of 10%.

An improvement in ROTE from 5% to 10% would generate a significant uplift in valuation from the expected IPO price of £1.80 (implying just under 0.6x book). However, at a ROTE of even 10%, we would argue the bank would still be destroying shareholder value through reinvestment. As such it does not fit our investment process of looking at good businesses with strong prospects, irrespective of the execution risk.

Only some mortgages in the US are non-recourse, and some states with recourse mortgages were amongst the worst hit in the crash. With respect, I hope other points made here are not addressed so casually.

Casually because not the major point of the article. Largely non-recourse. Thanks.

They’re not “largely non-recourse,” Roger – lenders in 39 of the 50 US states do, in fact, have recourse to the borrower’s assets beyond the house, by pursuing deficiency judgments. This is a point of fact which can be easily verified via Google, which points us to academic research produced by the US Fed on this specific issue:

https://www.richmondfed.org/~/media/richmondfedorg/publications/research/working_papers/2009/pdf/wp09-10r.pdf

It may be harder for US lenders to recover beyond the value of the home vis-a-vis Australian lenders, but it’s factually incorrect to say that US mortgages are largely non-recourse.

“It may be harder for US lenders to recover beyond the value of the home” = “largely”

“However, we continue to monitor employment conditions as a key indicator of default risk”

Just wondering which data sets you follow for this information as the ABS data appears to be inherently unreliable and volatile.

Unfortunately, changes to the survey by the ABS makes the employment data less reliable at present as well. But there are sources, whether it be the SEEK employment ad data, or simply our discussions with a broad range of companies in the market.

A few super quick points for discussion:

You mention that for a crash you need ‘forced sellers’, which will presumably only occur if interest rates spike or unemployment goes up.

What about a third potential source – a generation of baby boomers currently negatively geared, who need to sell? If prices stagnate (let alone go down), there is only so long that investors will subsidize properties that are draining cash. And once the first round start selling, and house prices potentially decrease, it only puts additional pressure on negative gearers still in the market.

In addition, and this has been discussed on this blog elsewhere, there is the issue of baby boomers (empty nesters) being forced to sell in order to fund their retirements. Given that non-real estate assets and super woefully low for most boomers retirement needs, selling their biggest asset (house) and downsizing could put additional pressure on the market.

Do you see these as potential issues?

The absence of buyers can force sellers where there were no forced sellers previously.

Stuart,

An excellent discussion about the operating market for banks. It took quite a long time before we got to the crux of the matter – what will be the growth rate in the bank’s loan book & what will be their return on assets. Surprisingly, no discussion about the regulatory environment for banks (possible impacts of Basel 3) and the potential for changes in the level of capitalisation over the short to medium term. Surely no banking discussion can be complete without the consideration of what these changes may do to the returns on bank equity?

Best regards, Rob

Hi Rob,

As you point out, regulatory changes will be a major factor influencing valuation and returns going forward. The process of regulatory change in response to the lessons from the Financial Crisis is still in its infancy despite the significant amount of capital raised last year. Interestingly, comments from the Basel Committee in January suggested that further increases in capital requirements will be less than the market had expected. APRA followed up those comments fairly quickly indicating that the major banks have not quite achieved what it considers to be ‘unquestionably strong’ capital ratios just yet. However, the Australian regulator also indicated that the banks should be able to raise their capital ratios to meet this measure ‘in an orderly fashion’. This implies APRA believes that increased capital ratios are likely to be achieved through organic capital retention rather than requiring the large equity raisings we saw last year.

The rate of organic capital generation and retention will depend on: 1) the banks ability to lift margins using their pricing power and/or cut costs, 2) bad debt provisioning and impairment remaining under control, 3) the growth rate of loan books. We believe that there is scope of the banks to improve their cost to income ratios in the medium term but we are also mindful of the threat as well as the opportunity presented by disruptive technologies. The pricing power of the banks has been demonstrated by the out of cycle mortgage rate rises passed through in the second half of last year. The question is how much of this will be competed away through discounting in the front book. Overall we expect operating margins to improve in near term. This is likely to be at least partially offset by increasing provisioning charges. As we discussed in the blog, this has little impact on our perception of sustainable ROE and valuation given we adjust our earnings to a long term provision level. On loan book growth, we expect this to slow as the steam comes out of the mortgage market, offset by a recovery in business lending. Interestingly, the RBA’s bank statistics for December indicate that loan book growth has held up at ~6.5%. If this rate of growth continues, it will make it harder for the banks to lift their CET1 ratios to the required level through organic capital generation without either cutting dividend payout ratios, or partially underwriting future DRPs. Cuts to the payout ratio would be taken very negatively by retail shareholders, but given the outlook for the marginal ROEs generated by the major banks relative to the cost of equity (albeit lower than historical due to continued pressure to increase capital), shareholders are better off with higher growth and a lower dividend in terms of the total return outlook.

The last aspect of the regulatory puzzle to think about is in regards to liquidity requirements. The discussion around regulatory risk is likely to shift toward this issue over the next few years. To date, the market has almost entirely focused on capital requirements, due to the implications of increased capital requirements being more easily identifiable and quantified. However, increased liquidity requirements have the potential to impact valuation significantly as well, and are likely to impact some banks more than others.

I hope this helps.