The great recession that never was. Should we sound the all-clear? No

Panic and speculation about a significant economic downturn in the U.S. have been part of financial discourse over the past year. Many analysts and most economists were expecting a recession, a negative shift in the economic tide, and that fear is what prevented many investors from buying equities and missing out on the gains since November.

More recent data indicates that this much-anticipated recession may not occur after all, and sentiment is most certainly shifting.

But while the trumpets sound the all clear on the economy, the stock market has already surged, leaving it at risk of a sell-off if investors decide to take profits on the realisation of their optimistic economic view.

Earlier this year, the consensus amongst economists was that the U.S. was heading towards a recession, which would see growth rates slow. More recently the consensus has shifted to a ‘soft landing’ with growth down but still positive (which I remind investors, when combined with deflation has always been positive for innovative growth stocks, since the 1970s).

Michael Gapen, a U.S. economist at Bank of America, is an example of the growing number of economists who believe growth will not slow down as much as earlier expectations had anticipated. “We have revised higher our outlook for growth in economic activity this year and next, and no longer expect the economy to fall into a mild recession,” Gapen noted recently.

I recently outlined some of the reasons a recession hasn’t ensued, including relatively high levels of disposable income thanks to a large cohort of mortgagees who have fixed and refinanced their mortgages at ultra-low rates for 30 years, and an even larger cohort who have no mortgage at all and are therefore also unimpacted by the U.S. Federal Reserve’s (Fed) recent rate increases.

Adding weight to this new “no landing” narrative, Jerome Powell, the Fed chair, recently commented that central bank staff no longer foresee a recession in 2023. Goldman Sachs has also reduced its prediction of a recession within the next year, down to a 20 per cent chance from an earlier estimate of 25 per cent.

On the corporate front, for Q2 2023, 51 per cent of S&P 500 companies have reported actual results at the time of writing, and 80 per cent of those S&P 500 companies have reported a positive earnings per share (EPS) surprise. Meanwhile, 64 per cent of S&P 500 companies have reported a positive revenue surprise.

Elsewhere economic indicators, such as the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow forecaster, project an accelerated economic growth rate of 3.9 per cent in the third quarter of 2023. This would make it the quarterly performance since late 2021.

Despite the Fed just raising interest rates to the highest levels since 2001, the economy shows signs of resilience rather than regression. And employment data remains a foundation stone for the strength. Wage growth is stable, unemployment rates remain low, and the automatic data processing (ADP) Employment Report revealed that the U.S. added 324,000 private payroll jobs in July, surpassing the expected 190,000.

Simultaneously, the central bank appears to be firming its grip on inflation, with the official price measure hitting its lowest level in nearly two years.

Nevertheless, achieving the Fed’s two per cent inflation target remains a challenge, and while there are projections for another Fed rate hike at the September meeting, followed by a slower rate-cutting cycle over the next few years, progress on the inflation may remain problematic and cause bouts of equity market volatility.

But not all is as it seems. For one, for Q2 2023, the blended earnings decline for the S&P 500 is minus 7.3 per cent. If minus 7.3 per cent is the final number for the decline for the quarter (only 51 per cent reported so far), it will mark the largest earnings decline reported by the index since Q2 2020, which was minus 31.6 per cent.

Elsewhere, U.S. treasury yields are again above four per cent. At the time of writing, U.S. 10 year treasury bonds are back to 4.107 per cent. While they briefly touched this level in March and July, the last time they traded above this level was in October and November last year, when the equity market was on its knees.

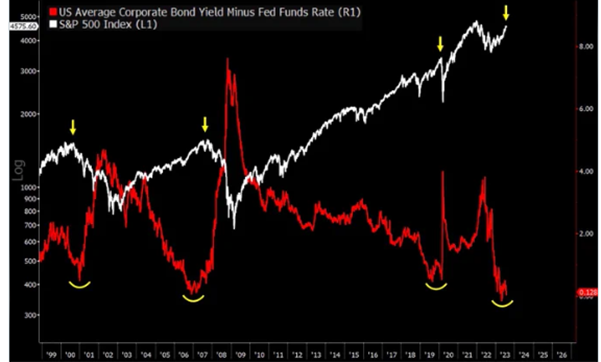

Meanwhile, corporate bonds now yield only 0.12 per cent more than the Fed funds rate. As Figure 1 reveals, since the turn of the century, every time credit spreads were at such suppressed levels, an equity market sell-off transpired.

Figure 1. Corporate bond yields versus Fed Fund and S&P500

Source: Bloomberg, Crescat Capital LLC.

And let’s not forget, recently 90 per cent of the yield curve was inverted – a measure that has correctly predicted every economic recession in the last half-century.

It is worth keeping in mind contractionary monetary policy (tightening rates) influences the real economy with a lag and the typical credit contraction has yet to transpire. Of course, it might not, but a credit contraction would lead to further economic issues.

What was once anticipated as a foregone recession is now being seen as an opportunity for the economy to showcase its resilience. As Jerome Powell recently noted, “we do have a shot [at a soft landing], and my base case is that we will be able to achieve inflation moving back down to our target without the kind of really significant downturn.”

And a soft landing doesn’t mean equity investors haven’t already purchased in anticipation of a soft landing, leaving them to sell on realisation of that soft landing. The equity market is not immune to a setback, which might be considered due, after the NASDAQ100, for example, surged more than 40 per cent this year.