The Case For and Against Consumption Growth: Part 1

For some time, we have outlined our concerns regarding the growing constraints on the Australian household sector due to various elements. In the first part of a two-part blog I will identify one argument. Will the slowing or a reversal of household wealth creation have negative implications for many companies?

Here are the various elements:

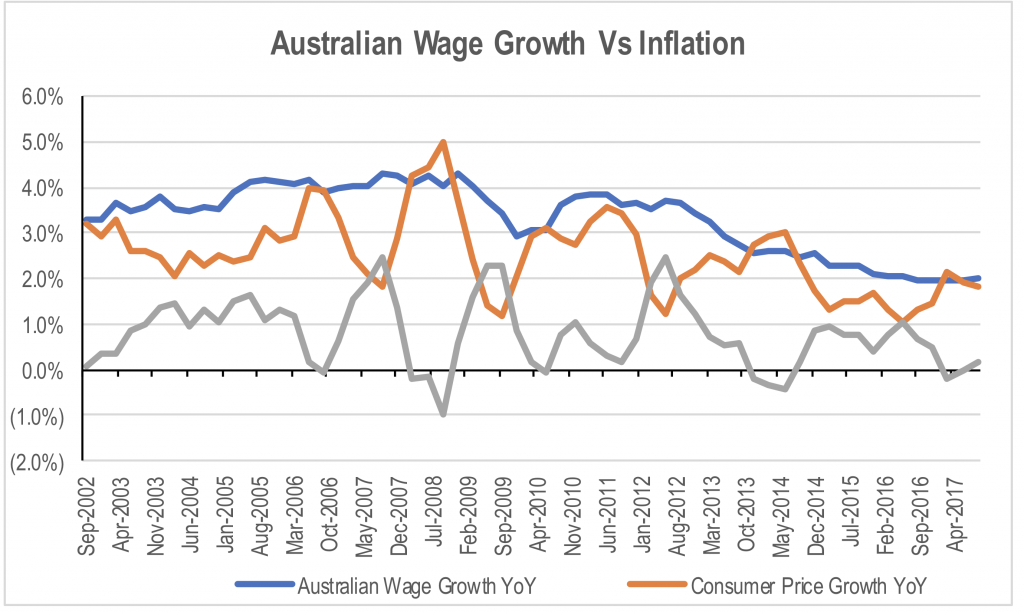

- Continued weak wages growth relative to growth in the cost of living (or real wage growth).

- Unprecedented levels of household debt, and

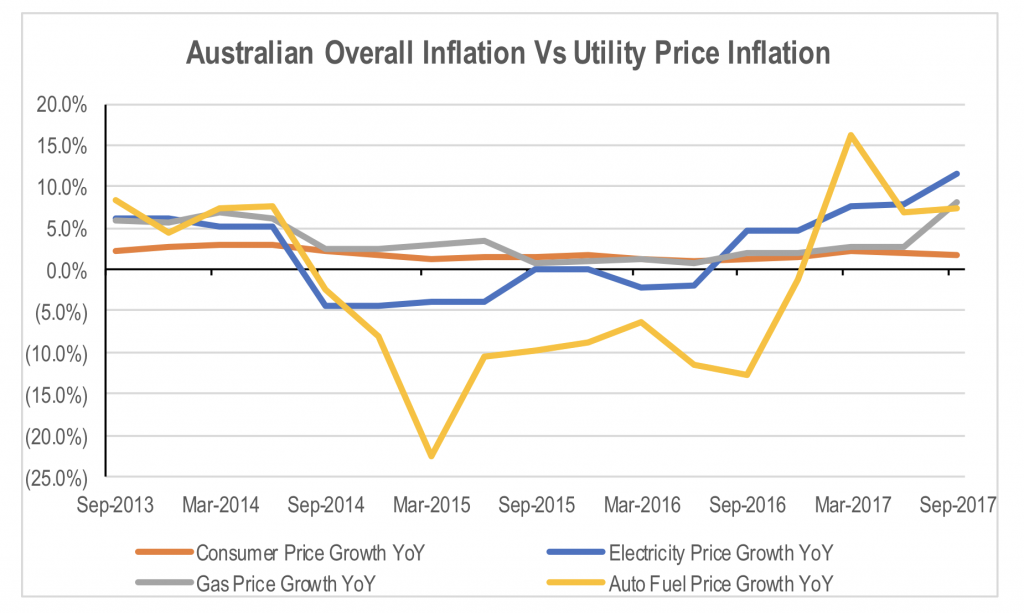

- accelerating non-discretionary cost inflation through higher energy prices, which have gone from deflationary over the last two years to become a drain on household budgets.

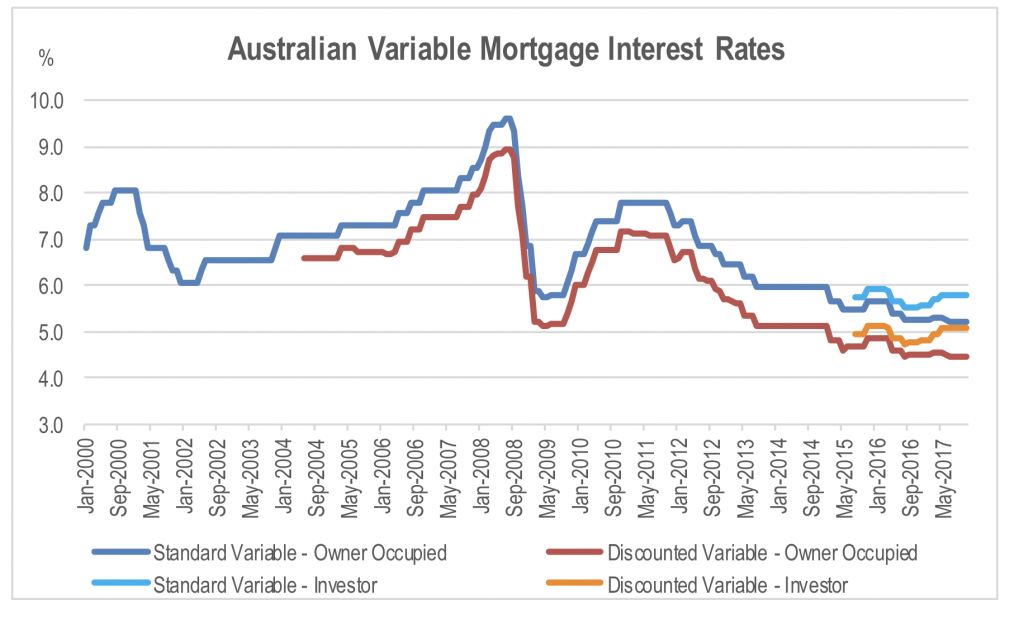

- As well as rising investor mortgage rates due to regulatory actions feeding through to bank pricing.

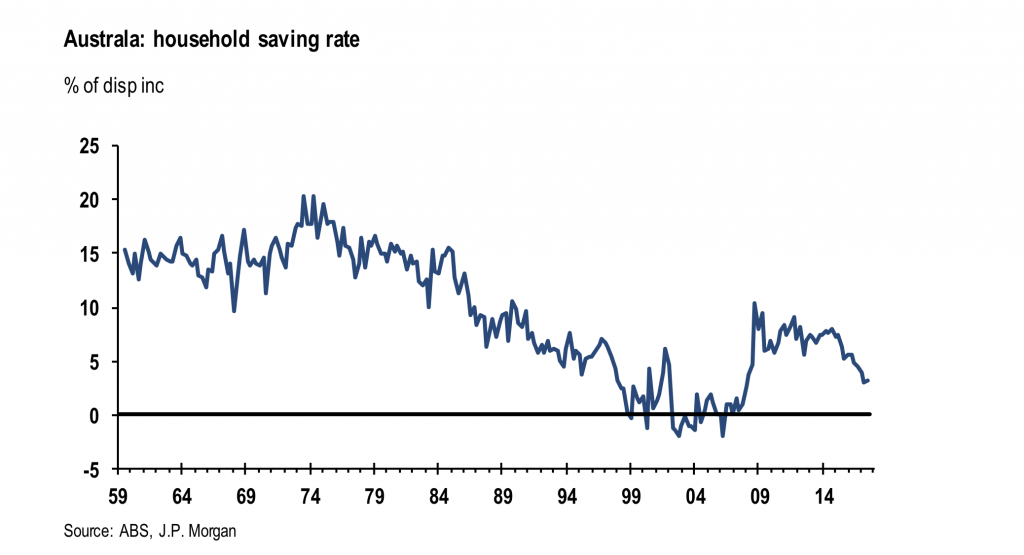

The offsetting factor that has held up consumption activity has been falls in the household savings rate, which has reduced from 7.9 per cent of disposable income at the end of 2014 to 3.2 per cent in September 2017.

The current savings rate is well below long term levels, but still above levels seen in the last decade prior to the GFC. While this can be explained by a number of factors, the wealth effect created by very strong appreciation in residential housing prices over the last few years provided households with the ability to drawdown on ‘paper profits’ to finance consumption through increased debt. It also enabled households to leverage newly created property equity from price increases into additional property purchases, further fuelling the residential property price appreciation.

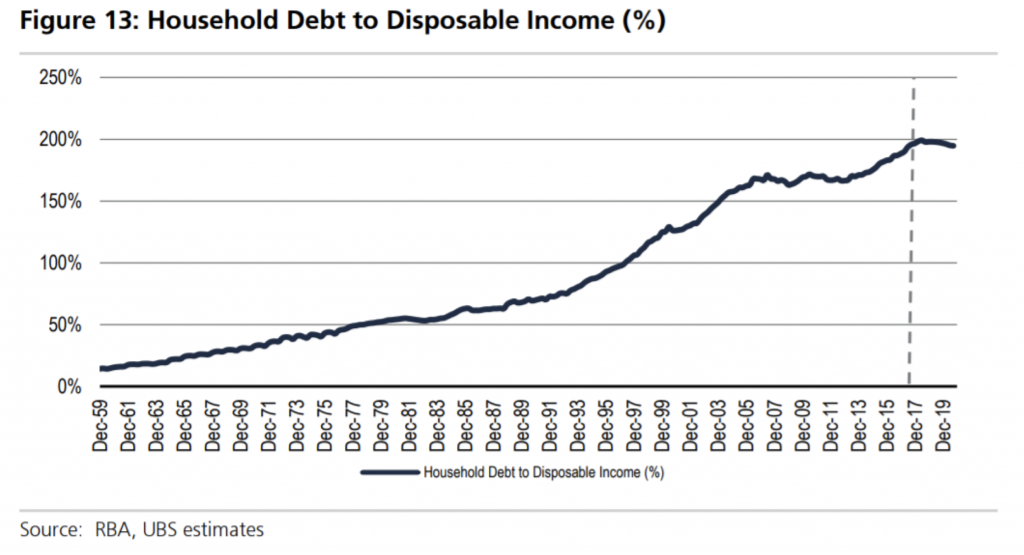

This has driven the level of household debt in Australia to record levels as a percentage of disposable income.

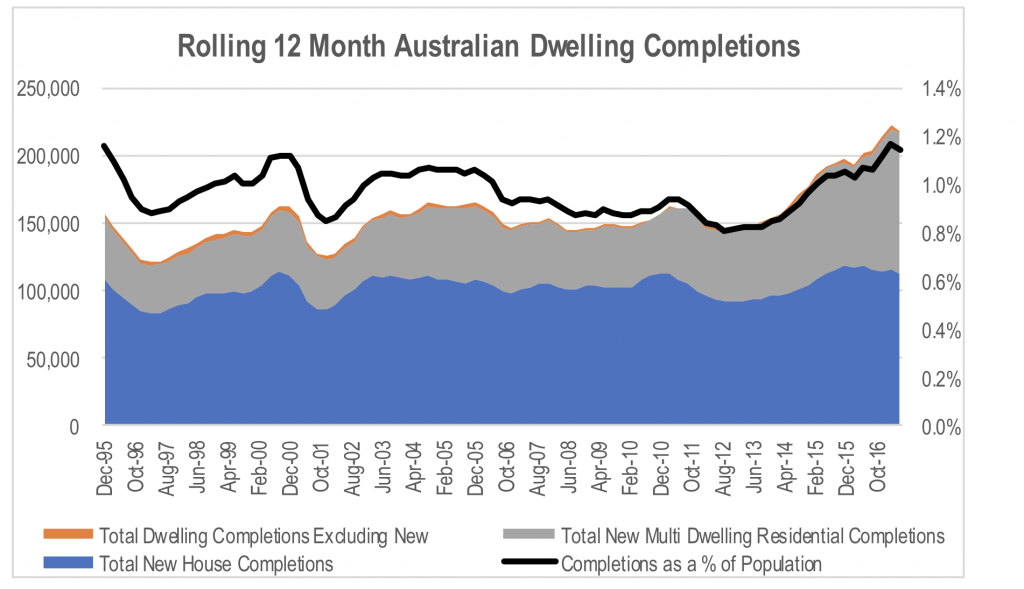

The problem is that the price mechanism in both the residential property and mortgage markets are doing their job. Higher property prices have stimulated construction, particularly multi-dwelling developments. This can be seen through the acceleration in dwelling completions as a percentage of the population.

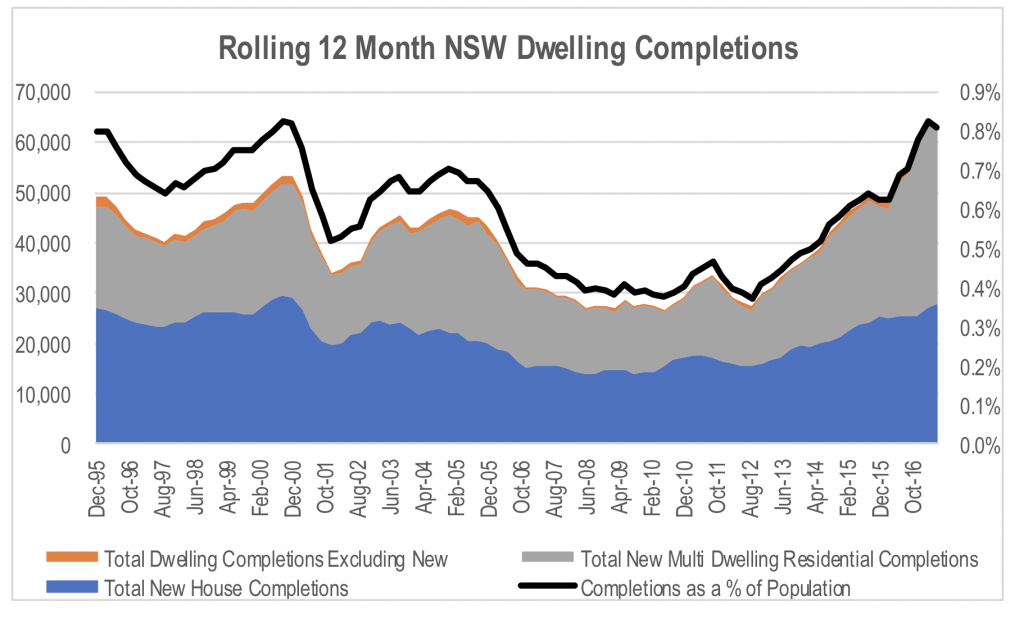

This acceleration in dwelling construction over the last few years is even more stark when looking at the data for NSW in isolation. This highlights the concentration of the construction boom around certain geographic centres.

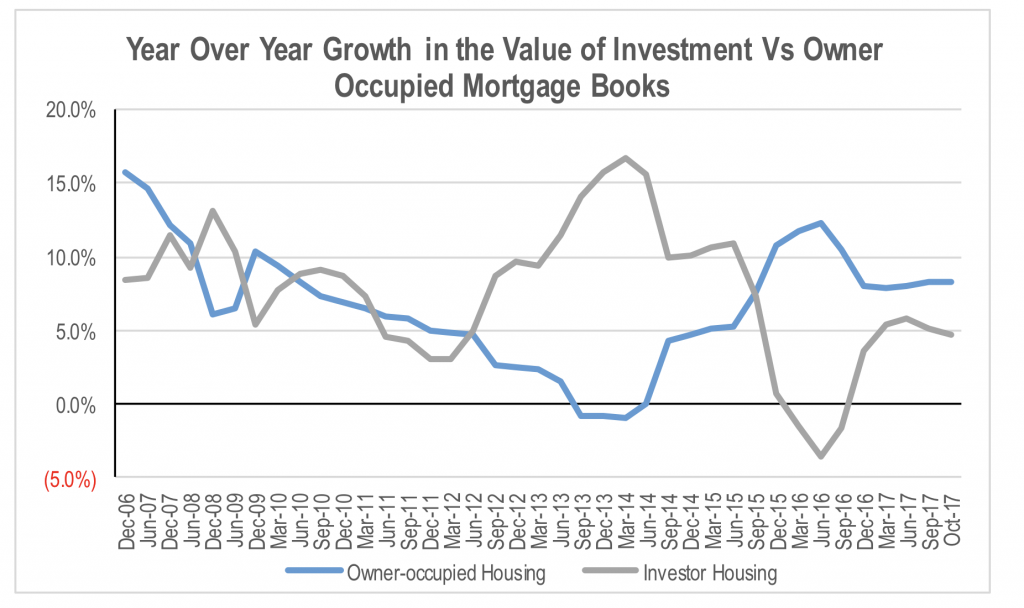

At the same time, caps imposed by APRA on bank mortgage lending that are designed to reduce lending into perceived pockets of heightened risk, namely investment property lending (10 per cent cap on investment loan book growth) and interest only mortgages (30 per cent cap on the proportion of new mortgages that can be interest only), have seen mortgage rate increases targeting these specific product areas in order to ration demand for these product features.

The cap on investor loan growth initially saw a reclassification of older loans from investor to owner occupied, which clouded the underlying impact on investor loan growth. However, since then, RBA data shows a moderation in investor mortgage book growth while owner occupied loan book growth has remained resilient.

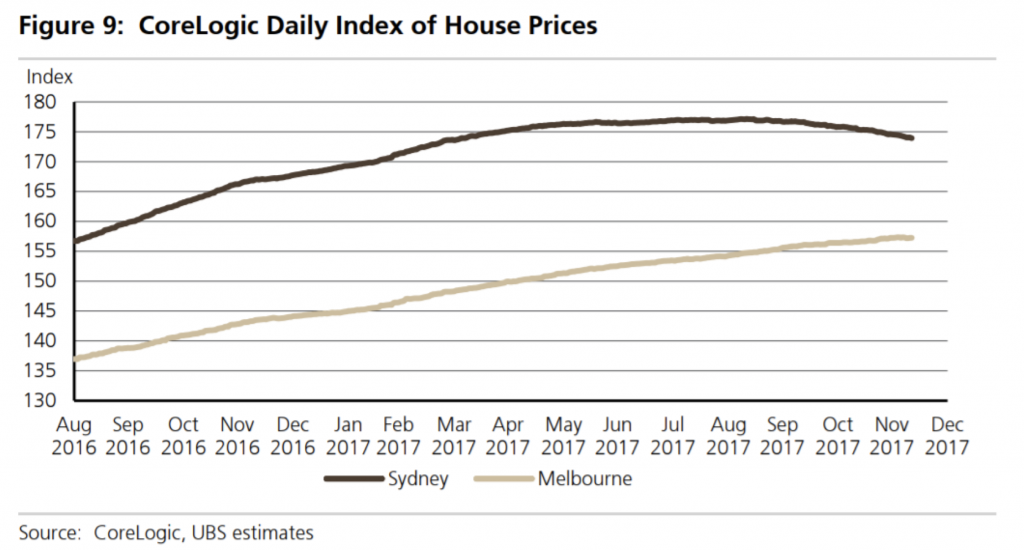

With the supply response to price appreciation growing, and a key source of demand being curtailed by macroprudential curbs on the mortgage market, it is not surprising that residential property prices appear to have reached or rolled over from their top in the Sydney and Melbourne markets.

The issue is flat or falling residential property prices has the potential to see the underlying support for discretionary spending from declines in the savings ratio move into reverse. Declining residential property prices results in declining household wealth and requires an increase in the savings ratio to preserve the long-term standard of living for households unless there is some other offsetting factor.

Slowing or a reversal of household wealth creation will restrict consumers from using increasing debt levels to grow or potentially even maintain consumption levels in the face of weak wages growth and accelerating non-discretionary cost growth. This would have negative implications for any company exposed to discretionary household spending in Australia, such as retailers, and providers of consumer finance, such as banks.

When combined with the potential for structural change to the composition of retailer gross margins as a result of the growth in the online channel, further fuelled by Amazon’s launch in the Australian market, it is not hard to be concerned about companies that are leveraged to the Australian household. This has been a source of fear for the market for some time now. In part 2, I will look at the alternative argument.

The Montgomery Global Funds own shares in Amazon

This post was contributed by a representative of Montgomery Investment Management Pty Limited (AFSL No. 354564). The principal purpose of this post is to provide factual information and not provide financial product advice. Additionally, the information provided is not intended to provide any recommendation or opinion about any financial product. Any commentary and statements of opinion however may contain general advice only that is prepared without taking into account your personal objectives, financial circumstances or needs. Because of this, before acting on any of the information provided, you should always consider its appropriateness in light of your personal objectives, financial circumstances and needs and should consider seeking independent advice from a financial advisor if necessary before making any decisions. This post specifically excludes personal advice.

INVEST WITH MONTGOMERY