The artificial intelligence web of deals

Earlier this month, Nvidia – the company at the heart of the artificial intelligence (AI) boom – announced it had agreed to invest up to US$100 billion in OpenAI to help the Large Language Model (LLM)-maker fund its data centre build out. In turn, OpenAI agreed to fill those data centres with Nvidia Chips.

If it sounds odd, it is. That’s because it’s akin to convincing Nick Scali to buy you a house if you agree to fill it with Nick Scali’s furniture.

In fact, the Nvidia/OpenAI deal was immediately criticised for being ‘circular’.

Not to be deterred, OpenAI then signed another deal, this time with Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) to deploy 6 gigawatts of AMD Graphic Processing Units (GPUs) in its data centres at a cost of tens of billions of dollars. In return AMD effectively issued OpenAI with equity. AMD then, essentially, trades equity for a guaranteed customer, ensuring its chips find a home in OpenAI’s data centres.

Within days of the deal with Nvidia, OpenAI had also signed a deal with Oracle to purchase US$300 billion in computing power (Data centres) in the U.S.

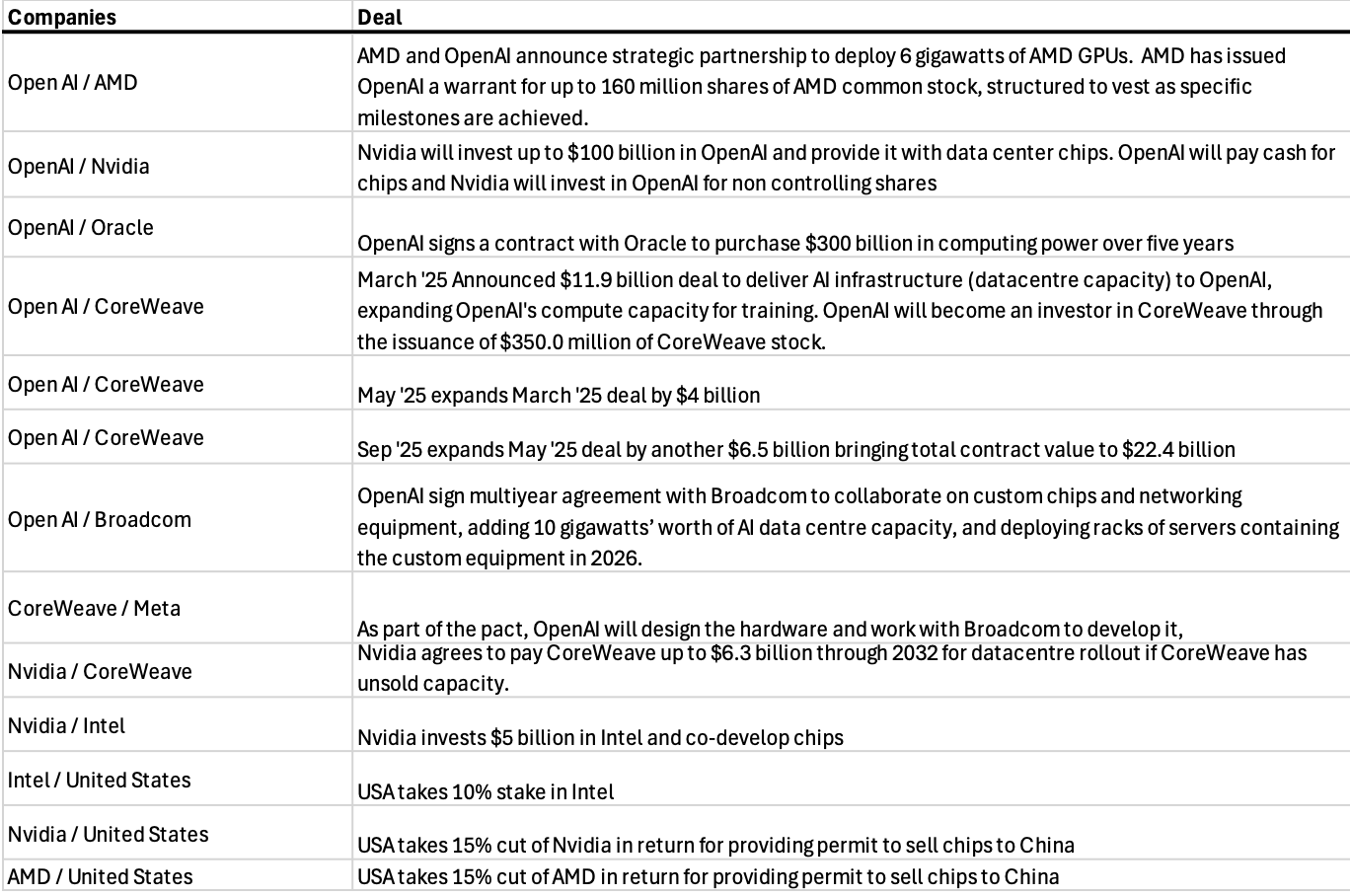

Table 1., lists a handful of deals that reveal the extent of the spending by AI-related firms on, well, on each other.

Perhaps taking a page out of Donald Trump’s own playbook, the pace and scale of the investments by AI companies have flummoxed analysts who now worry the web of deals is being undertaken to prop up a boom that has forgotten the underlying technology’s ability to generate sufficient revenue to produce satisfactory return on investment (ROI)’s remains largely speculative and possibly elusive.

The looming issue for me is the concept of ‘one in – all in’. If sentiment turns, they all go down together. They probably would anyway.

And it’s not like there’s no debt involved. While the AI ‘build’ – Major tech companies pledged a record US$320 billion in capital expenditures for 2025 – has mostly been self-funded to date, Morgan Stanley estimates capital expenditure (capex) is forecast to reach US$2 trillion by 2028 and US$1.5 trillion of that may need to be debt-funded.

Major tech companies pledged a record $320 billion in capital expenditures for 2025, Fortune wrote. That number is growing so much that – a whopping $1.5 trillion of which will come from various forms of debt, according to Morgan Stanley.

Debt is fine if a company can fund it, but as Forbes recently noted, Oracle is already losing US$100 million per quarter on its data centre rentals to OpenAI, despite signing its US$300 billion, five-year deal with them.

Table 1. AI Deal-a-Thon

Source: Montgomery Investment Management

Not to be outdone, and amid fear of missing out (FOMO) perhaps, Elon Musk recently announced a US$20 billion equity and debt raise. Elon Musk’s company XAI, which operates the Grok LLM, will buy Nvidia processors, subsequently renting them out. For it’s part Nvidia will commit up to US$2 billion to Musk’s raise.

It sounds a little like you giving me a billion to buy your stock and then you use that money to buy my stock and then I use it to buy your stock…and so on, and so on.

Indeed, Goldman Sachs analyst James Schneider pointed out in a research note that “NVIDIA’s investments flow out as funding, returns are realised via GPU sales, therefore inflating the reported growth.”

In other words, while each transaction promises to fuel the next technological revolution, beneath the hype lies a pattern of interconnected, self-reinforcing transactions – aka Shell Game – that some say echo troubling chapters from stock market history. (Shell Game – an anecdote used in business to describe the act of using psychological tricks to convince ‘potential players’ the legitimacy of ‘the game’.)

I don’t know of anyone who has aggregated all the spending and then estimated what the total addressable market size needs to be to generate an appropriate ROI, and then worked out whether it’s possible. And what if the downstream buyers of AI tools decide it’s not worth the effort? According to MIT, earlier this year, 95 per cent of AI pilot projects failed to generate a sufficient return and many internal AI projects were abandoned.

While aggregate numbers don’t exist, some individual estimates do. According to Reuters, OpenAI needs to generate US$125 billion in revenue just to break even, and it’s not expected to get there for another four years. Until then, OpenAI has to finance its losses by issuing shares.

Nevertheless, most investors think the AI boom will continue, that downstream users will discover creative new uses for AI and LLMs, revenue growth will accelerate and current investment will become profitable.

Another possible scenarios, albeit one with a lower probability, is the one my 20-something son suggested. His idea is that LLMs have already maxed out their abilities. ChatGPT 6, 7 and 8 won’t produce the improvements we saw with the early versions. He thinks the money flows will shift from LLMs to robotics. Initially both will receive funding as investors conflate the two, but eventually one needs to slow so the other can grow.

The most pessimistic scenario includes OpenAI being unable to fund its US$14 billion annual loss. The tie-ups revealed in Table 1., would then see CoreWeave forego 60 per cent of its revenue, in turn unable to pay interest on its US$14.5 billion of debt, and file for bankruptcy. Fears of contagion would then see further growth curtailed, in turn questioning the validity of stretched price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios. While this scenario is currently viewed as the one with the lowest probability of transpiring, the probability is non-zero.

What should you look out for?

The first thing is to remember that when stock prices turn exponential, the gains become unsustainable. Rarely do vertical ascents end with prices going sideways. They usual reverse quickly.

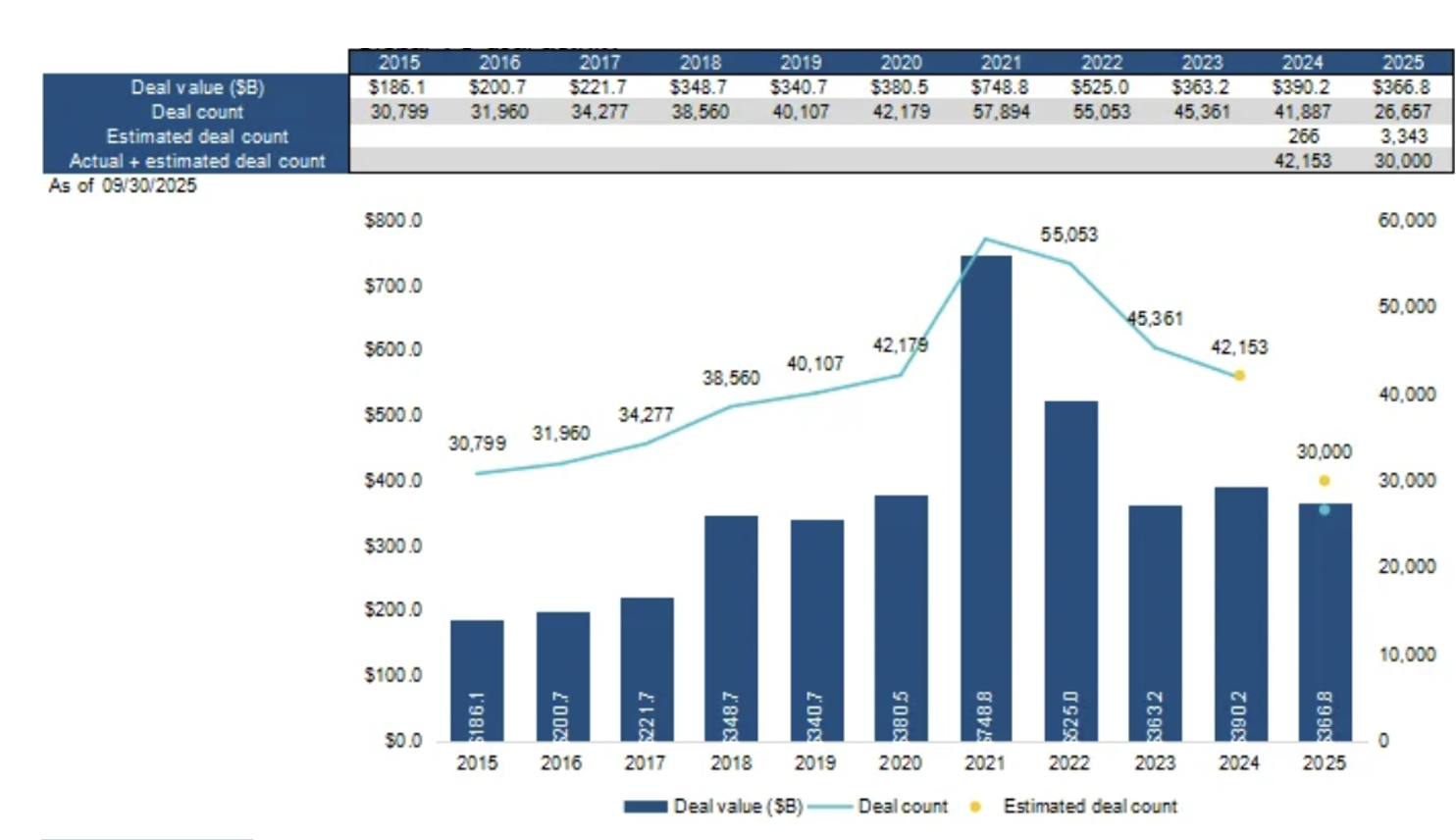

Figure 1. Global venture capital (VC) deal activity

Source: Pitchbook

It’s also worth watching OpenAI’s quarterly announcements and comparing the cash burn rate to revenue growth. Market analysts will also be tracking customer acquisition and churn rates. Eventually, companies reach a glass ceiling in total customers, and they are forced to spend more to win new business as old customers leave. That’s churn.

CoreWeave’s mountain of debt requires US$250 million in quarterly interest payments. Operating income in the last quarter was just US$19 million. Keep an eye on that while also watching the pace of VC deals on data provider Pitchbook. According to Pichbook, venture capital (VC) firms have injected US$192.7 billion into artificial intelligence startups so far this year. That’s more than half of the US$366 billion total in VC deals globally.

If VC deal flow into AI ventures begins to slow, however, it could signal a waning appetite and a recalibration of risk. Given the long-term nature of VC capital commitments, investors may be forced to liquidate listed stocks to generate cash if their risk perceptions change.

Lessons from the past

History is littered with precedents where similar circular business models inflated bubbles, only to precipitate sharp market corrections.

The most obvious parallel is the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s, where tech firms engaged in reciprocal advertising and cross-selling to artificially boost revenues.

Back then, companies like WorldCom and Global Crossing traded network capacity in circular swaps, inflating reported growth and valuations until the house of cards collapsed in 2000-2002, wiping out trillions in market value.

Vendor financing was rampant then too – Cisco, much like Nvidia today, loaned money to startups who then bought its routers, creating illusory demand that evaporated when the bubble burst.

The 1929 stock market crash was accompanied by leverage spirals where banks and brokers extended credit in circular loops, and in the 2008 financial crisis, collateralised debt obligations (CDOs) created by banks packaging and reselling subprime mortgages led to a global meltdown when underlying assets soured.

There are differences of course. We don’t have the IPO mania of the 2000 tech boom, systemically important banks aren’t carrying AI securities on their balance sheet, as they did the CDOs in 2007 and investoirs are presumably much more sophisticated than those of 1929.

But investor behaviour remains unchanged, and the immediate market reactions to recent AI deals have been euphoric. AMD’s stock surged 24 per cent on its OpenAI announcement, while Oracle jumped 43 per cent after its tie-up, minting billions for insiders like CTO Larry Ellison. Nvidia’s market cap has ballooned to $4.5 trillion, making it the world’s most valuable company.

If AI monetisation lags – OpenAI admits it won’t be cash-flow positive until the decade’s end – valuations could deflate rapidly, as previous hype-fuelled tech booms have done. And given the interconnectedness of the AI ecosystem, if one sneezes, we may all catch cold.