The artificial intelligence boom sounds the alarm – is this the Dot.com bubble 2.0?

Wall Street’s S&P 500 dropped more than one per cent last week, and the tech-heavy Nasdaq fell three per cent. It’s really nothing in the scheme of things. That’s because the Nasdaq 100 is up more than 130 per cent in three years, and the S&P 500 is more than eighty-five per cent higher since October 2022. Nevertheless, last week’s turn-down was the worst week for the Nasdaq in seven months. What the index price declines perhaps don’t reflect, however, is a much sharper shift in the market’s risk appetite.

Why? Well, first, there’s the market valuations; as Figure 1., reveals, the Cyclically Adjusted Price-to-Earnings (CAPE) Shiller Ratio on the S&P 500 has only ever been higher than current levels once since the year 1870.

Figure 1. Shiller Cyclically-Adjusted P/E (CAPE) ratio.

Source: Multpl

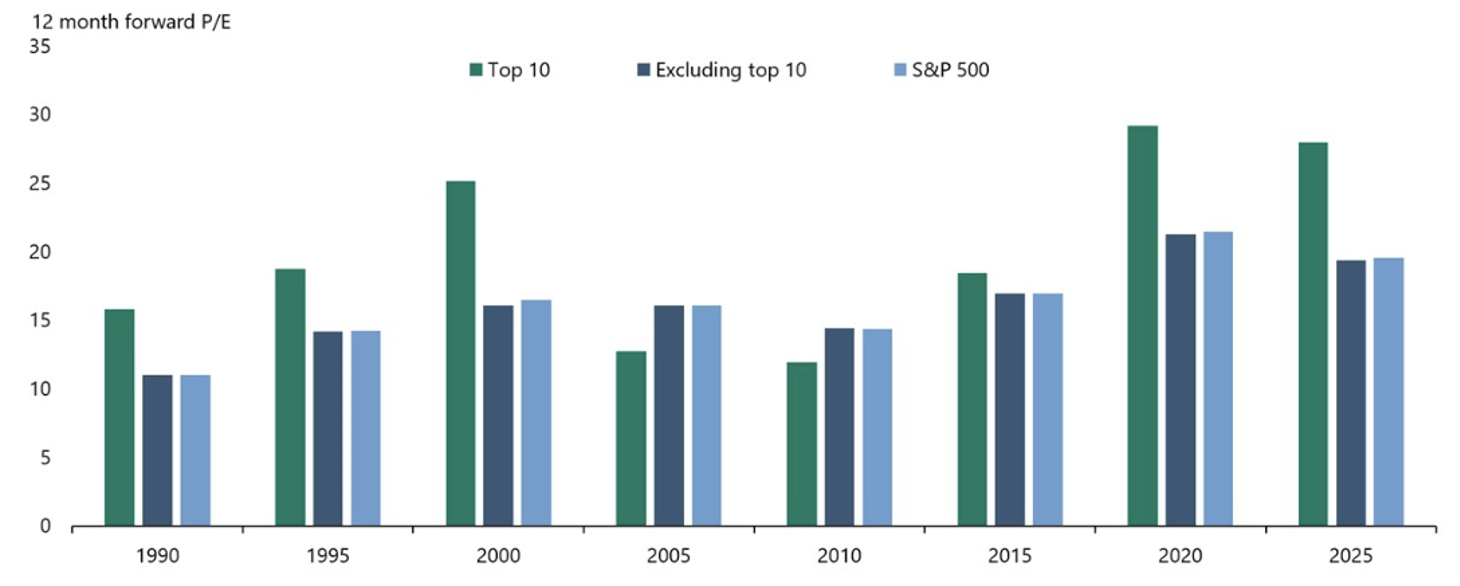

Another chart going viral at the moment is produced by Torsten Slok of Apollo. As Figure 2., reveals, valuations can be described in a variety of different ways, some confirming and some disabusing the idea of an AI Bubble.

Figure 2. The AI Bubble is bigger than the IT bubble in the 1990s

Source: Torsten Slok

Slok’s chart reveals the difference between the IT bubble in 2000 and the AI bubble today is the top 10 companies in the S&P 500 today have a higher forward earnings multiple and are therefore potentially more overvalued than they were in 2000. It’s also worth noting that AI stocks accounted for 85 per cent of the S&P500’s gains so far in 2025, and just 41 AI-related companies now make up almost 50 per cent of the S&P500. It’s a huge bet.

The sceptics emerge

That bet has spurred a growing conga line of experts and commentators now describing the AI boom as an incontrovertible bubble, and comments by OpenAI’s Sam Altman and the company’s CFO, Sarah Friar, last week (more on that in a moment) haven’t helped.

If you have invested through past booms and busts, you’ll be acquainted with the cyclical nature of technology hype cycles, where innovation drives capital inflows, while unambiguously positive expectations of the transformative potential of the technology drive share prices, at least until the reality of competitive capitalism and fundamentals reassert themselves – slowing the capital inflows and reversing the share prices.

Marko Papic, chief geopolitical strategist at BCA Research, argues ‘with certainty’ that the current overexcitement will culminate in substantial losses – and trillions in value will be erased. Papic identifies three possible triggers for a crash: a landmark initial public offering (IPO), a massive merger akin to the AOL-Time Warner’s US$350 billion (inflation-adjusted) deal that capped the dot-com boom of 2000, or underwhelming AI adoption rates. The latter has already been reported in an MIT study that found 95 per cent of 300 U.S.-based firms that had invested somewhere between US$35 billion and US$40 billion in generative AI saw their pilot projects fail to deliver.

On the flipside, permabear Ray Dalio – who has, admittedly, called many recessions that never transpired – is now warning of a melt-up, rather than a meltdown. He believes monetary policy will exacerbate the AI froth. Dalio believes the Federal Reserve’s (the Fed) recent pivot from quantitative tightening (QT) to potential easing, against a backdrop of fiscal deficits, resilient equity markets, low unemployment, and inflation above target, could ignite a “melt-up” reminiscent of late 1999 or 2010-2011. He argues expected monetary policy settings risk monetising debt and inflating asset prices beyond sustainable levels, setting the stage for a policy-induced reversal.

Meanwhile, Michael Burry – the famed short seller who was celebrated in Michael Lewis’s book The Big Short for shorting the U.S. housing bubble of the mid-2000s before it popped, recently established multi-billion-dollar short positions against Nvidia and Palantir, citing decelerating cloud revenue at Amazon, Alphabet, and Microsoft, capex levels mirroring the dot-com peak and the circular financing arrangements we have noted here in earlier blogs, such as those between OpenAI and Nvidia.

Whether or not Burry’s US$1.1 billion bet pays off isn’t the point. It is however a reflection of growing scepticism in the durability of the AI boom. Investors are at now beginning to look beyond the hype. And that’s when markets become vulnerable to short and sharp sell-offs.

Altman’s OpenAI

Of course, at the epicentre of it all stands OpenAI, whose aggressive expansionist dream epitomises the sector’s ambitions and its vulnerabilities. Valued at US$500 billion, OpenAI has committed over US$1.4 trillion in multi-year spending on chips, computing power, and infrastructure with partners including Amazon (US$38 billion recent deal), Microsoft, Oracle, and Nvidia.

The issue, however, is that OpenAI’s annualised revenues are projected to be US$20 billion this year. If those revenues don’t grow, the spending commitments would require 70 years of revenue to pay for them. And that’s assuming all the revenue is directed to the partners rather than internal costs such as staff and taxes. To reduce the time scale to something palatable to investors, revenue has to grow much more quickly.

In a rare stumble, the company’s CFO, Sarah Friar, recently floated the concept of government “backstops” to facilitate financing. Market observers quickly jumped on the statement as an admission of the need for government ‘bailouts’. She later clarified that this was advocacy for policy support to build industrial capacity, not direct aid.

On a podcast streamed on X last week, OpenAI CEO, Sam Altman, was asked how he’s going to fund the US$1.4 trillion of spending commitments with just US$13 billion of annual revenues. He first explained that revenue would grow substantially from ‘US$13 billion’ (as it has from US$3.7 billion in 2024) and then said, “If you want to sell your shares, I’ll find you a buyer,” before shutting down the line of questioning with, “Enough.”

Trust me

But Altman also admitted, perhaps unintentionally, that there’s a huge ‘trust me’ component to projected demand for AI tools including OpenAI’s yet-to-be-released AI-powered consumer hardware.

“We are taking a forward bet that it will continue to grow, and that not only will ChatGPT keep growing, but we will be able to become one of the important AI clouds, that our consumer device business will be a significant and important thing, that AI that can automate science will create huge value,” added Altman.

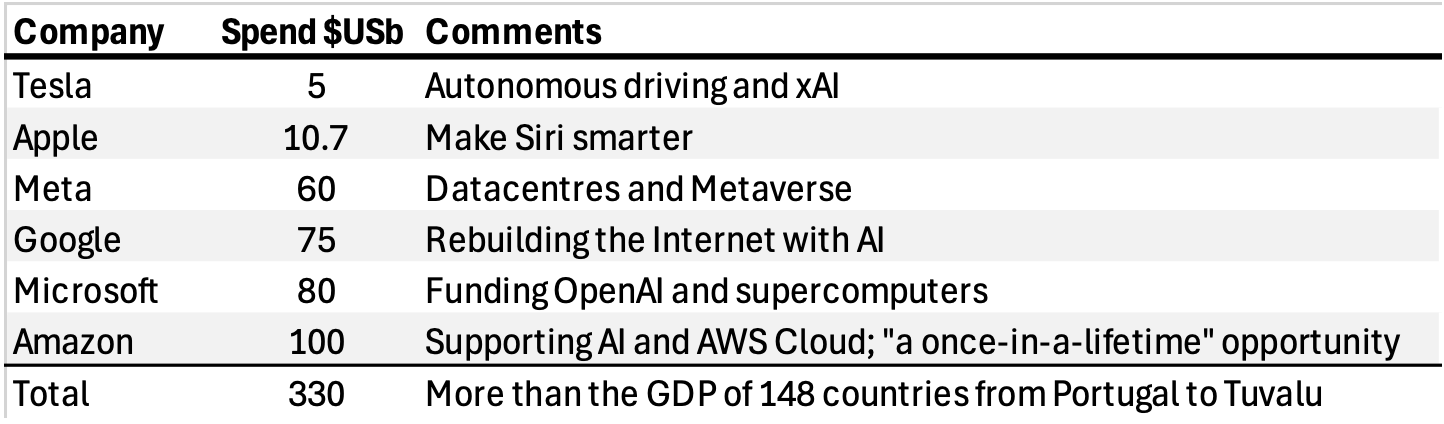

‘Trust me’ was also implied recently by Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg, who said his company was intentionally “front-loading” compute, noting, in the “very worst case”, Meta will have “pre-built for a couple of years.” Zuckerberg has also been quoted as saying even misspending US$200 billion is “worth it”, because if they move too slowly, they’re out of the competition.

Table 1. The AI Spend-a-Thon

Nothin’ to see here. Roundtrippin’ baby!

In what some are describing as an attempt to ‘pretend to extend’, many of the AI players are funding each other in a round-robin of deals that on paper looks like a spaghetti junction. Pulling out some of the early deals is however enough to raise your eyebrows.

Take the earliest deal where Microsoft’s investors inject US$58 billion into OpenAI. OpenAI then announces it’s effectively routing most of that capital back to Microsoft as payment for data-center capacity. Microsoft then ostensibly takes the returned funds and purchases Nvidia Graphic Processing Units (GPUs). Nvidia, flush with cash, channels a portion of those proceeds right back into OpenAI as an investment.

With the exception of Nvidia and Microsoft’s investment in OpenAI, each leg can be booked as revenue: Microsoft logs hosting fees, and Nvidia records chip sales. The circular flow inflates top-line figures, which in turn lift valuations and share prices when shares are priced as multiples of revenue.

OpenAI recently signed a US$300 billion compute agreement with Oracle. Oracle promptly committed tens of billions to Nvidia hardware. Nvidia, in response, pledged up to US$100 billion into OpenAI –contingent on OpenAI buying still more Nvidia silicon to consume the promised funds.

Nvidia sits at the centre, selling Graphic Processing Units (GPUs) to every major player – Microsoft, Meta, Google, Amazon, Oracle, and OpenAI itself – then reinvesting portions of the proceeds into the same customers. This, as I have described previously, the arrangements are a subsidisation of customer purchases akin to Nick Scali and JB Hi-Fi vendor financing its customers into new homes so they can buy Scali’s furniture and JB Hi-Fi’s appliances.

Or, as one analyst explained, Nvidia supplies the picks and shovels, Oracle leases the acreage, and OpenAI excavates the pit.

Is it sustainable? Well, all the activity has drawn huge crowds to view the hole that’s been dug, as well as vast numbers of investors to invest in it. The problem is that none of the players has struck gold. Well, not yet. So is it sustainable? Time will tell.

Who will be the victims of hype (The 4th Industrial Revolution)?

There are, of course, buyers and sellers for every traded share, and that means there are those who believe there’s more room for the AI boom to run. They point to declining U.S. interest rates, which will ease borrowing costs, enabling household leverage, orderly bond markets despite commentators’ debt concerns, and a geopolitical détente between the U.S. and China mitigating the risk of an escalating trade war trade (although some believe last week’s agreement between China and the U.S. is merely a pause to allow the players to position more robustly ahead of an all-out conflict).

And then there’s the fact that, unlike the dot.com bubble of 1999/2000 (at the time ‘the next big transformational thing’), where companies worth billions on paper were profitless, today’s AI infrastructure build is being driven (if not entirely funded) by dominant and profitable businesses with proven and diversified business models, robust balance sheets and huge cash flows. Moreover, unlike the dot-com boom, the development of AI is seen as geopolitically and strategically critical and is therefore more likely to have government backing.

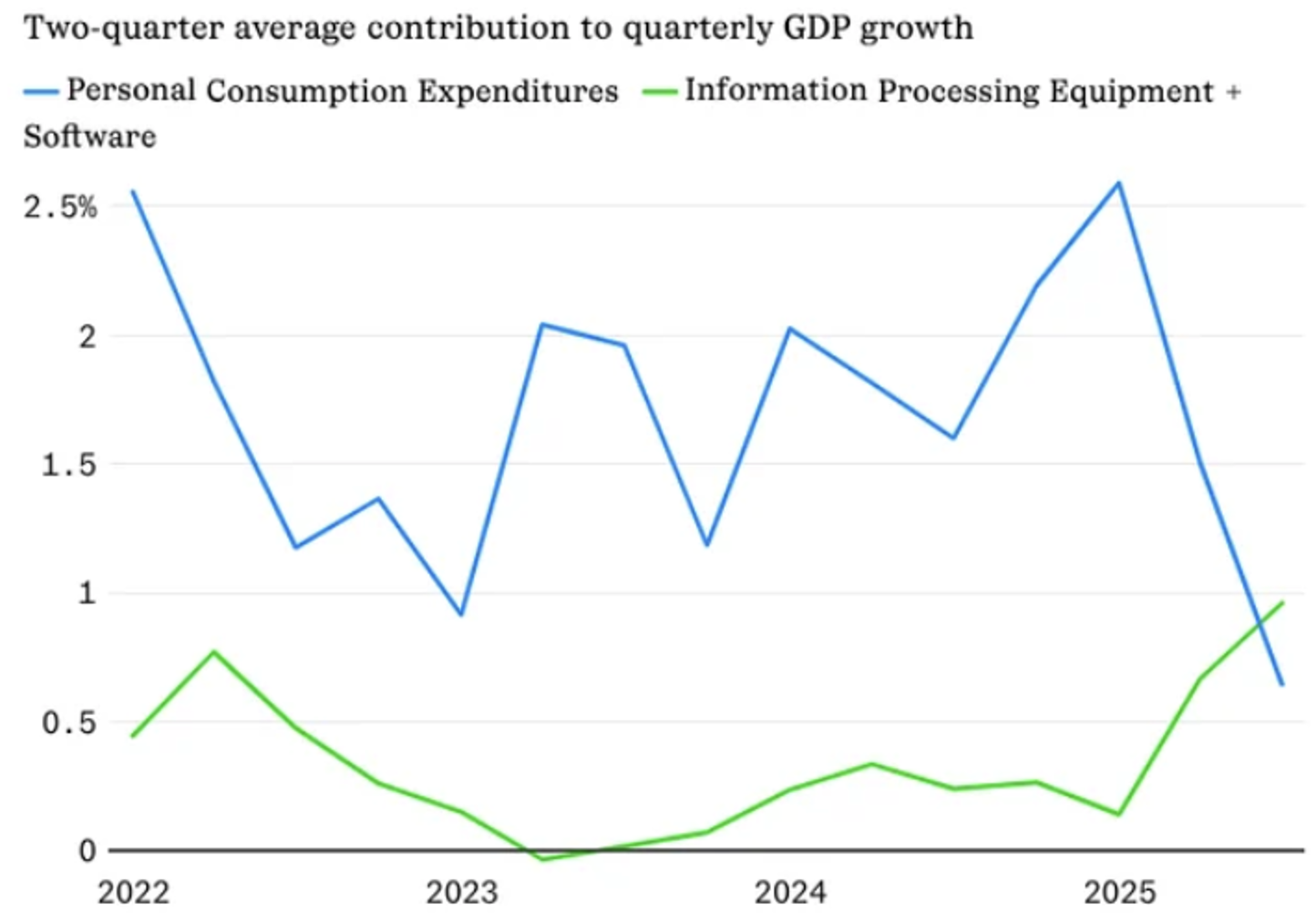

Figure 3. AI spending is crowding out U.S. consumption

Source: Bloomberg, Renaissance Macro

Of course, governments aren’t immune to investment hype. They, too, consist of people. Remember the state and local governments that lost billions during the subprime crisis that triggered the Global Financial Crisis (GFC)? The fact that people run governments makes it almost certain they will be among the victims if a correction wipes trillions from overall valuations.

Even those at the centre of the artificial intelligence (AI) boom admit there could be a bubble. According to a report by Alex Heath from The Verge published on 15 August, 2025, Sam Altman told a small group of reporters, “When bubbles happen, smart people get overexcited about a kernel of truth,” rhetorically asking, “Are we in a phase where investors as a whole are overexcited about AI?”, answering, “My opinion is yes”. Altman then qualified the warning by asking, “Is AI the most important thing to happen in a very long time? My opinion is also yes.”

Finally, it’s worth keeping in mind that the AI boom is fuelling economic growth in the United States to such an extent that, without the AI spending, the economy might already be close to a recession. AI spending already appears to be crowding out consumption (Figure 3.). Therefore, were the AI boom to crash, it would take the U.S. economy with it. That would ensure the selling would not be confined to the AI names. An AI sell off would take everything with it as investor rush to the exits ahead of a recession.

Don’t bet on a crash. Just rebalance

For investors, the imperative is vigilance and considered portfolio rebalancing. AI’s transformative potential may justify continued selective exposure, but exuberant AI spending commitments, even more exuberant valuations and unproven returns, demand disciplined portfolio management. You should be portfolio rebalancing at least annually anyway; this year is no exception.

Important Note:

Investing is not a game of mutually exclusive options. You don’t put all your money in stocks when you think the market will rise, nor do you sell everything if you think the market might fall. The consequent taxes and frictional costs, as well as near-certain inability to correctly time the highs and the lows, will ensure that mutually exclusive investing will cost you.

The right approach is to ‘rebalance’. Let’s assume your portfolio starts in 2022 with 30 per cent equities, 30 per cent property, 30 per cent private equity and fixed interest, and 10 per cent alternatives. Then assume after three years, equities have doubled while everything else has remain unchanged. That scenario would mean the portfolio has risen by 30 per cent overall, but now the equities are 46 per cent of the portfolio, property is 23 per cent, private credit /fixed interest is 23 per cent, and alternatives are about eight per cent.

Rebalancing means, in this example, bringing everything back to its original weight. That means selling some of the equities and reallocating the proceeds to the other asset classes, so that each asset class’s weight returns to its starting level.

Rebalancing encourages some profit taking when asset prices are high and adds to asset classes that have underperformed relatively. Another benefit is that most predictions for a stock market crash will be wrong. By rebalancing, rather than exiting, exposure to equities is retained and benefits the investor if markets continue to soar. Indeed, there are many who believe we are only at the beginning of a ten-year artificial intelligence (AI) boom.

Disclaimer:

The Polen Capital Global Growth Fund own shares in Nvidia, Alphabet, Microsoft and Amazon. This article was prepared 11 November with the information we have today, and our view may change. It does not constitute formal advice or professional investment advice. If you wish to trade these companies you should seek financial advice.