Food and energy prices hurt living standards

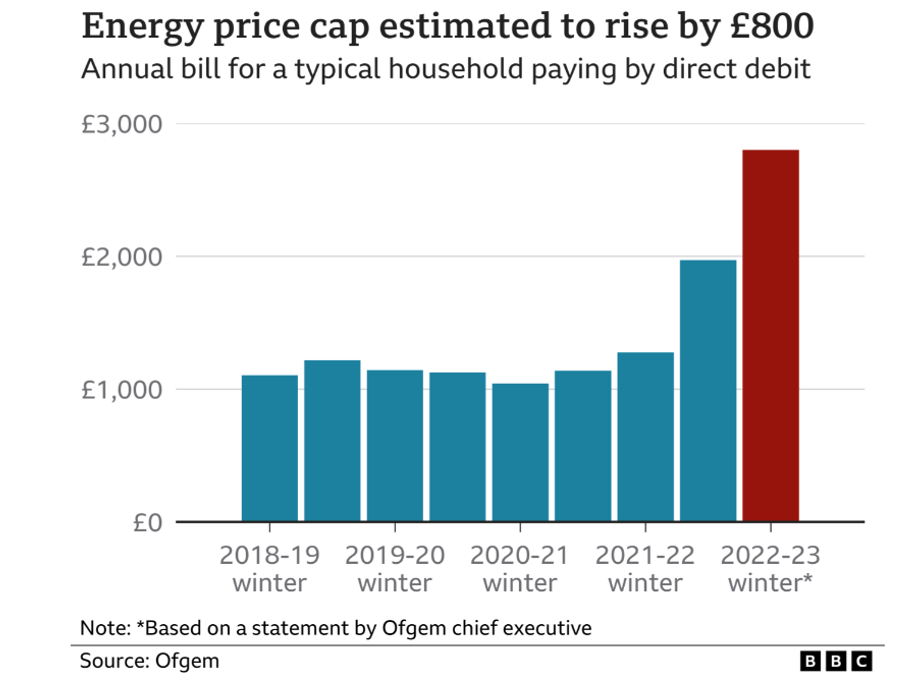

In last Thursday’s Chanticleer, my friend Tony Boyd made the following stark observation: In Britain, the regulator warned the electricity price cap is likely to rise to GBP2,800 (A$5,000) from October 2022, a staggering increase of GBP1,500 (A$2,700) in 12 months. It is estimated there are about 6.5 million British households in fuel poverty, defined as spending 10 per cent of income on energy.

The table below analyses the price of various food and energy related commodities over the past year, and it would be a fair assessment to argue many families around the Western World are now under enormous food and energy insecurity.

|

Commodity |

Unit |

Price per Unit |

Price movement over the past year |

|

Crude Oil |

bbl |

US$110 |

+66% |

|

Natural Gas |

MMBtu |

US$8.93 |

+205% |

|

Oats |

5,000 bushels |

US$651 |

+75% |

|

Wheat |

bushel |

US$12.25 |

+66% |

|

Coffee |

37,500 lbs |

US$212 |

+39% |

|

Feeder Cattle |

50,000 lbs |

US$163 |

+23% |

|

Soybean Oil |

60,000 lbs |

US$78 |

+18% |

The Australian Energy Retailer announced on Thursday that it would raise default market electricity prices for households by 8.2 per cent in NSW and 5.5 per cent in Queensland.

Australian consumers are in a much better place than those in Britain, where regulators warned the household electricity price cap is likely to rise to a staggering 120 per cent rise on a year earlier. It is estimated around 6.5m households in Britain will experience energy poverty, defined as spending 10 per cent or more of their income on energy. For context, there are an estimated 27.8m households in the UK meaning one household in four (and nearly 17m people) will be suffering from energy insecurity.

According to the Office of National Statistics, the average UK household spends 20 per cent of their income on food and drink, and with the price increases listed above this implies close to 30 per cent of the average household income needs to be set aside for their food and energy requirements.

This crunch on UK living standards – coming from significantly higher food and energy prices – is frightening, particularly now the Bank of England thinks inflation could challenge the 10 per cent level later in the 2022 calendar year.

The one positive from this crunch on living standards, if any, is that Central Banks cannot be too aggressive in the tightening cycle of their official cash rates, or they will plunge their economies into a hard landing.

I believe many market commentators will likely bring down their forecasts for both the number of official cash rate increases and the magnitude of those increases. And assuming this thesis proves correct, the severe pressure we have experienced on markets since late-2021 may soon subside.