Could the Government’s lending restrictions backfire?

The law of unintended consequences states that actions – particularly by government – can have adverse effects that are unanticipated or unintended. This law could soon play out as a result of lending restrictions placed on the major banks by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA).

Regulators have imposed a number of prudential measures on the banks over the last few years to help protect the economy from systemic financial risk. In the middle of 2015, APRA introduced a 10% cap on investment proportion loan book growth. From 1 July 2016, APRA changed risk weight calculations on mortgages determined by the major banks from accredited risk modelling. This was designed to increase the average risk weighting on mortgages by around 60% for the major banks.

Despite these changes, residential property price appreciation in Sydney and Melbourne has continued unabated, increasing concerns about a property market bubble and the inevitable consequences for the broader economy when the bubble bursts.

This has led to press reports that the Government and regulators are looking at further constraints on property lending through the imposition of even tougher lending restrictions on banks.

From an investment perspective, what does this mean for the banks and the broader Australian economy?

If we look at the impact of the measures taken to date, we note a few things. While it is true that the growth in the size of bank investment loan books slowed in late 2015 and into 2016, the rate of growth in overall bank mortgage books remained largely unaffected. This indicates that the reduction in growth rate of investment property mortgages was largely a function of a reclassification of existing mortgages from investor to owner-occupied. This temporarily hid the true rate of growth in investment property mortgage books. Consequently, once the data started to lap the imposition of the 10% growth cap, investment property mortgage book growth started to reaccelerate back toward previous levels.

Source: RBA

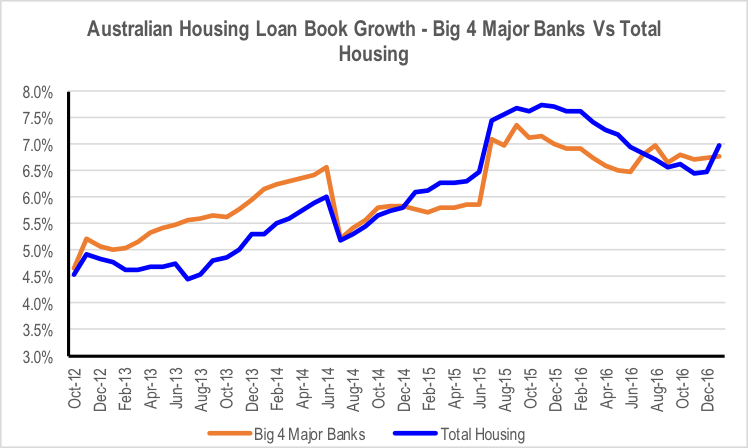

However, what these measures did do is temporarily reduce the rate of growth in mortgage loan books for the major banks relative to the overall system.

Source: RBA, APRA

The other impact of regulatory restrictions is being felt through mortgage rates. Any year 11 economics student can tell you that if supply is reduced as a result of an external factor, demand will be rationed in a capitalist economy through the price mechanism. In other words, as bank lending is restricted, the banks will increase the price of loans (ie the mortgage rate) to reduce demand to levels in line with the restricted supply. Hence, we have seen major bank variable and fixed mortgage rates on investment properties increase relative to funding costs and owner occupied mortgage rates.

If the Government and regulators impose further restrictions on mortgage loan book growth, such as the halving of the cap on investment property loan book growth to 5% or additional increases in some mortgage risk weights, expect mortgage interest rates to continue to increase relative to funding costs.

Out of cycle mortgage rate increases provide a positive driver of revenue for the banks through a widening of net interest margins, but this will be offset by a negative impact on loan growth. Higher mortgage rates will also increase the risk of an acceleration in mortgage arrears and defaults. Increased pressure on heavily geared households, combined with continued high levels of residential completions, increase the risk of asset issues for the banks and the broader economy.

But the other problem is that tighter regulatory controls of the banks that are designed to target a specific segment of the market are unlikely to be an effective tool in reducing the risk to the economy from the property bubble. This is because the liquidity from the resulting accommodative monetary policy of RBA does not just disappear because there are restrictions on bank mortgage lending capacity. The demand remains in the market, and in an increasingly innovative world, alternative providers of financing will accommodate the excess demand through non-bank financing solutions.

We have already observed this occurring in the commercial property market over the last couple of years with mezzanine finance tapping capital from high net worth individuals searching for yield. We also note the AFR recently reported comments from Mortgage Choice that there is plenty of non-bank financing capacity available to property investors irrespective of whether APRA further restricts bank level capacity.

The problem with this is that ARPA and the RBA have less control over these non-bank sources of funds. This could create an irony in that by trying to impose restrictions on the banks to prevent a bubble destabilising the broader economy, regulators could lose control over the rate of credit expansion by driving demand to these less regulated sources of financing, leading to an increase in economic risks.

The growth in less regulated non-banks in the 1970s and the resulting reduction in control over the banking system was one of the reasons why the banking system was deregulated in the early 1980s. Macro prudential policies being implemented at the moment run the risk of a repeat performance.

To quote Princess Leia, “The more you tighten your grip.., the more star systems will slip through your fingers.”

This post was contributed by a representative of Montgomery Investment Management Pty Limited (AFSL No. 354564). The principal purpose of this post is to provide factual information and not provide financial product advice. Additionally, the information provided is not intended to provide any recommendation or opinion about any financial product. Any commentary and statements of opinion however may contain general advice only that is prepared without taking into account your personal objectives, financial circumstances or needs. Because of this, before acting on any of the information provided, you should always consider its appropriateness in light of your personal objectives, financial circumstances and needs and should consider seeking independent advice from a financial advisor if necessary before making any decisions. This post specifically excludes personal advice.

INVEST WITH MONTGOMERY

Agree with Paul , GB and Nathan. APRA doesn’t try to regulate the financial system Stuart, its not allowed to and can’t possibly, only institutions within its charter. I think they know that they have no control on the rest of the system, even if their regulation certainly influences it indirectly as you mentioned. Its a question of blame. The regulation is a good idea, can’t blame theme for moving risk into the unregulated part. The government needs to implement other policy or a different regulatory regime then.

Regulating other part of the market will require ASIC, and co-ordination between various government bodies.

Stuart, you and Paul are both right. Paul’s point is that APRA doesn’t have any mandate beyond prudential regulation of financial institutions defined within its charter. Paul’s critique is right in that you are suggesting that its regulation has backfired. But APRA’s regulation was never intended, nor does it legislatively intend to implement government policy with respect to the financial system generally. The headline and conclusion of your piece tend to suggest otherwise. You are right Stuart in that regulation has unintended consequences and your point to an important new risk or escalation of risk as a result of the regulation. Both truths sit consistently with each other.

APRA is not the government. It does not set government policy. “Our mission: to establish and enforce prudential standards and practices designed to ensure that, under all reasonable circumstances, financial promises made by institutions we supervise are met within a stable, efficient and competitive financial system.” The measures you describe constitute APRA fulfilling its mandate, they probably won’t work, but you giving them far greater a task in the premise of your article than is warranted.

APRA regulatory restrictions are designed to influence (improve) the stability of the financial institutions. Don’t over complicate things. The restrictions are not an antidote, panacea, broader credit market tool, macro economic policy tool, political policy or economic initiative despite what commentators, other interested parties or public opinion driven press releases say. I learnt this in year 10 economics class. Re-examine the premise of your point: that APRA action was designed to de-risk/stabilise the property market or the economy. It is misleading to suggest that a policy designed to influence bank stability is anything but that. Thanks for sharing though.

I’m not sure why you I think my premise is that APRA is trying to stabilise the property market. APRA’s goal is to ensure the stability of the financial system. The concern is that excessive gearing of the household sector is driving a property bubble. Given that banks are businesses that are highly leveraged to asset prices, having effectively sold a put to borrowers at the value of the principle, and 60-70% of the loan books of the banks are now residential mortgages, by definition the equity in the banking system is dependent on the value of those underlying assets. Banks without equity can’t lend and if the shock is large enough, it can threaten the stability of the entire financial system. APRA is trying to prevent increases in existing imbalances by placing restrictions on bank activity in segments of the market that it perceives to be at risk. My point is actually that focusing restrictions on the banks is merely likely to lead to growth in a shadow banking system that results in APRA actually having less control over the financial system.

I Agree with the below statement. It’s like playing whack a mole, If you hit one down 2 others pop up in other places with regards to loan regulation. Big themes for me are China and rising global interest rates and the rising USD – I think this will have the biggest impact overtime on property here. It’s crazy, APRA are close to releasing more “guidelines” / restrictions to reduce house price growth and in May the government will release first home buyer incentives (possibly involving super) to increase house price growth. Just nuts the way to try to pull and push at it..

“The problem with this is that ARPA and the RBA have less control over these non-bank sources of funds. This could create an irony in that by trying to impose restrictions on the banks to prevent a bubble destabilising the broader economy, regulators could lose control over the rate of credit expansion by driving demand to these less regulated sources of financing, leading to an increase in economic risks.”

Misleading headline calling it “the Government’s” lending restrictions. APRA is an independent statutory authority after all.

Fair comment. The headline really referred to the Government in its broader context rather than a political one.

Thanks for the note, Stuart. On balance, do you see the higher NIMS completely offsetting the increases in bad debts/arrears?

Hi William, I expect NIM to remain relatively flat due to the impact of lengthening the funding book, higher liquid asset holdings, front book competition and continued competition for deposits offsetting mortgage back book repricing initiatives. ANZ will get some mix benefit from continuing to run down its Asian institutional loan book, but this will come at the expense to relatively weak average loan book growth due to this strategic reduction in exposure.

To the extent that business lending growth exceeds mortgage growth, there might be some NIM benefit from mix shift, but I see current market expectations for NIM expansion to drive earnings growth as being optimistic.