Bees in the trap

I am reliably informed it’s one of the bigger trends on TikTok at the moment; miming to a mashup of 4 Non-Blondes’ 1993 song What’s Going On, and Niki Minaj’s Bees in The Trap, created by DJ Auxlord, a college senior studying psychology in Ohio.

On Martin Place in Sydney’s CBD, the viral song blasted from a local’s speaker, its hooks – “bees in the trap, bee, bees in the trap” and “what’s going on” – perfectly juxtaposed with the real bees queuing to buy gold just up the hill at ABC Bullion.

And as I was also reading another article about yet another record stock market high, I couldn’t help but wonder, what’s going on, and ask whether many stock market investors today are also bees in a trap.

Former McKinsey Co., analyst and Boston Herald journalist, Brett Arends, recently described the stock market as “the dumbest in history,” noting, “The alleged “wisdom of crowds” is so stupid, so often that it seems crazy to suggest that today’s stock market – which is, after all, just “the crowd” chasing money – is the craziest on record.”

I’d not level the ‘crazy’ label on every investor, but the collective irrationality has been highlighted recently by U.S. Investment management firm St James Investment Company, in their October 2025 Investment Adviser’s Letter;

“Data from the Natixis Global Survey for individual investors reveals a significant disconnect between investor’s return expectations and the risk they are willing to take. Overall, 83 per cent describe themselves as either conservative or moderate investors, yet they still expect to generate investment returns of 10.7 per cent above inflation over the long term. This means that investors need to be comfortable holding stocks indefinitely at the highest valuation levels in U.S. market history, while expecting still higher valuations. Based on history, current fundamentals, and realistic assumptions, today’s market price levels imply long-term market returns that are less than half of current expectations. In early 2000, an investor might have looked back on the spectacular returns of the S&P500 over the previous eighteen years, averaging nearly 20 per cent annually, and imagined that those returns could be extrapolated into the future. A similar gap in expectations exists today.”

Contemporaneous commentary just prior to the 2000 crash backs up St James’s observation. This next extract is from a paper titled, What Stock Market returns to Expect for the Future?, by then Institute Professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and Nobel Prize winner for his work on the analysis of markets, Peter A. Diamond, and delivered to the Social Security Administration of the United States in November 1999, just four months before the Dot.Com bubble burst, wiping 76 per cent from the NASDAQ Composite Index by October 2002:

“Popular perceptions may, however, be excessively influenced by recent events, both the high returns on equity and the low rates of inflation. Some evidence suggests that a segment of the public generally expects recent rates of increase in the prices of assets to continue, even when those rates seem highly implausible for a longer term (Case and Shiller 1988). The possibility of such extrapolative expectations is also connected with the historical link between stock prices and inflation. Historically, real stock prices have been adversely affected by inflation in the short run. Thus, the decline in inflation expectations over the past two decades would be associated with a rise in real stock prices if the historical pattern held. If investors and analysts fail to consider such a connection, they might expect robust growth in stock prices to continue without recognising that further declines in inflation are unlikely. Sharpe (1999) reports evidence that stock analysts forecasts of real growth in corporate earnings include extrapolations that may be implausibly high. If so, expectations of continuing rapid growth in stock prices suggest that the required equity premium may not have declined.”

In 1999, when I presented a Saturday stock market workshop for the ASX in their 300-seat Bridge Street auditorium, there was standing room only. In point of fact, the fire department turned up to move people out of the walkways, exits and staircases for safety reasons. When I asked attendees who would be happy if their fund manager delivered a 20 per cent return, only few hands were raised in reply. Why? Many had just experienced a year when the average first day gain for a NASDAQ Initial Public Offering (IPO) was 90 per cent.

A year later, after the Dot.Bomb, I was invited to give another presentation at the ASX auditorium. Less than 50 people attended. The crash had reset expectations.

Today’s expectations are equally unrealistic but are driven by a variety of factors, some of which are the same as those of past hallucinations and some that are new. Today, profound structural distortions, elevated valuations, and an investor cohort enthralled by momentum and prevailing narratives (artificial intelligence (AI)) top the list of factors fuelling what might potentially be reviewed in the future as another episode of irrational exuberance.

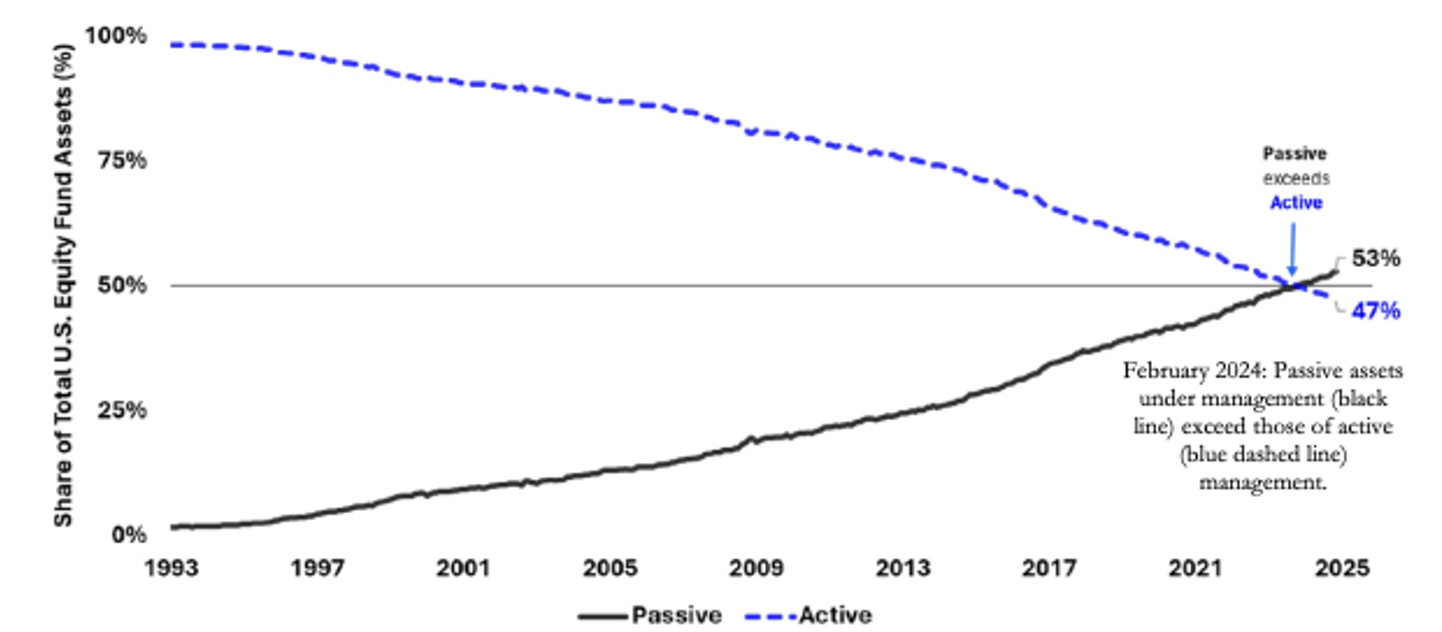

Figure 1. Passive strategies now surpass active investment management

Source: St James Investment Company, Research Affiliates, Morningstar

The dominance of passive index investing – now accounting for approximately 52 per cent of U.S. equity and bond assets under management, or US$15.4 trillion out of nearly US$30 trillion – has fundamentally altered market dynamics, prioritising mechanical flows over fundamental analysis. This shift, which has destroyed the validity of the intrinsic value concept, renders the present era particularly precarious.

Valuation extremes and volatility amplifiers

The S&P 500 currently trades at approximately 30.5 times trailing twelve-month earnings, while the Cyclically Adjusted Price-to-Earnings (CAPE) ratio, popularised by Robert Shiller, stands above 40. Its inevitable that such extreme metrics evoke those of historical bubbles, such as the one that preceded the 2000 dot-com crash.

Compounding this, the total U.S. stock market capitalisation exceeds 223 per cent of gross domestic product, per the Buffett Indicator – a threshold well above the one Warren Buffett has previously flagged as indicative of overvaluation.

Such valuations are inconsequential during short-term euphoria. They certainly cannot predict crashes. They are helpful, however, for predicting future long-term returns. At current levels, the CAPE Shiller ratio suggests low single-digit or even negative annual compounded returns over the next 10 years from the S&P 500.

Yet, the problems for investors don’t stem solely from overpricing. They also stem from an evolved market architecture.

As highlighted by Figure 1., passive capital allocation now exceeds allocations to active funds. One consequence of this is the erosion of traditional valuation discipline, with Benjamin Graham’s “margin of safety” supplanted by automated inflows driven by narratives about artificial intelligence, monetary debasement, and central bank interventions.

But, as momentum reigns, it transforms the market into a latent volatility amplifier.

A point on P/Es

Many investors today suggest that the price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios of the NASDAQ’s AI leaders are reasonable, especially compared to the elevated levels of the profitless internet startups of the 1999 Dot.com boom.

But P/Es can mask risk, and history has demonstrated this. My old investment committee colleague and friend Ashley Owen recently noted “The 1987 crash was a prime example of how the most widely used measure of pricing for shares and share markets – the ‘price/earnings’ ratio – can give investors a completely false sense of security, and fail to warn of massive levels of hidden over-pricing”, adding, “The seemingly low P/E ratios for individual companies and for the overall market suggested relatively cheap pricing, but actually masked enormous underlying problems because much of the reported (and audited) ‘earnings’ were the result of financial trickery, related-party deals, fudged valuations, circular transactions, and straight-out fraud.”

In fact, at the top of the 1987 boom right before the October crash, almost all of the aggressive (and now defunct) corporate raiders were trading on low P/E ratios, suggesting they were downright cheap relative to their ‘earnings’.

Today, it’s the related party deals of the AI companies that have me concerned.

Earlier this month, Nvidia – the company at the heart of the AI boom/Frenzy/Transformation/Bubble – announced it had agreed to invest up to US$100 billion in OpenAI to help the Large Language Model (LLM)-maker fund its data centre build out. In turn, OpenAI agreed to fill those data centres with Nvidia Chips.

If it sounds odd, it is. That’s because it’s akin to convincing Nick Scali to buy you a house if you agree to fill it with Nick Scali’s furniture.

In fact, the Nvidia/OpenAI deal was immediately criticised for being ‘circular’.

Not to be deterred, OpenAI then signed another deal, this time with AMD (Advanced Micro Devices) to deploy 6 gigawatts of AMD Graphic Processing Units (GPUs) in its data centres at a cost of tens of billions of dollars. In return AMD effectively issued OpenAI with equity. AMD then, essentially, trades equity for a guaranteed customer, ensuring its chips find a home in OpenAI’s data centres.

Within days of the deal with Nvidia, OpenAI had also signed a deal with Oracle to purchase US$300 billion in computing power (Data centres) in the U.S.

And it’s not like there’s no debt involved. While the AI ‘build’ – Major tech companies pledged a record US$320 billion in capital expenditures for 2025 – has mostly been self-funded to date, Morgan Stanley estimates capex is forecast to reach US$2 trillion by 2028 and US$1.5 trillion of that may need to be debt-funded.

Debt is fine if a company can fund it, but as Forbes recently noted, Oracle is already losing US$100 million per quarter on its data centre rentals to OpenAI, despite signing its US$300 billion, five-year deal with them.

The structural ramifications of passive investing

Passive strategies, encompassing index funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs), have ascended from marginal players to custodians of over half of U.S. equities. These vehicles allocate capital proportionally to market capitalisation, irrespective of fundamentals, fostering a self-reinforcing loop wherein rising prices attract further inflows, which in turn propel prices higher.

Passive strategies also undermine diversification: Investors holding multiple ETFs often unwittingly concentrate exposure in a handful of mega-cap entities. For instance, Apple reportedly features as a top holding in roughly 20 per cent of U.S. ETFs. You might think you are diversified, but the risks overlap.

As I mentioned a moment ago, a critical byproduct of passive investing’s dominance is the degradation of valuation signals. As Morningstar has observed, it “fuels the rise of mega-firms,” channelling capital to the largest entities regardless of merit, thereby distorting price formation and amplifying market concentration.

Morningstar’s claims have been validated academically. A study by Hao Jiang (Michigan State University), Dimitri Vayanos (London School of Economics; Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR); National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER)), and Lu Zheng (University of California), demonstrated in June 2024, that passive inflows disproportionately elevate the prices of the economy’s largest firms, particularly those favoured by speculative traders. This induces heightened idiosyncratic volatility, deterring active arbitrageurs and perpetuating mispricings.

These aren’t the only issues. While capital accrues to size rather than substance, rendering traditional ratios less indicative of underlying value, passive funds create another deception during bull markets. Passive fund buying produces a vision of ample liquidity as the market rises; however, during stress, redemptions from those same funds will trigger mechanical selling. Of course, today, selling by ETF operators to meet those redemptions will be concentrated in inflated mega-caps, exacerbating downturns. And that concentration, remember, is amplified by the heavy weighting in a few names by many varied ETFs and Index Funds, heightening vulnerability.

In essence, record all-time highs in the NASDAQ and the S&P 500 mask the fact that passive investing has created a fragile ecosystem in which dominance by default supplants merit-based portfolio allocation, fostering volatility and systemic risk.

The evolution of speculative bubbles

Speculative excesses are perennial, yet their expressions change. In the 1920s, it was investment trusts, laden with leverage and opaque cross-holdings, that were promoted to retail investors for the first time. Today, it’s vehicles like debt-financed Bitcoin Treasury companies like MicroStrategy, and platforms offering tokenised access to private firms such as Palantir and SpaceX via Robinhood. These instruments, marketed as democratised ‘opportunities’, obscure leverage and illiquidity, to say nothing of the regulatory quagmire.

What worries many observers is that when the market ascent halts, the facade of stability will crumble, ensnaring participants in a liquidity trap – a hallmark of this dangerous epoch.

Implications

Investors and their advisers should be rebalancing portfolios, taking profits from high-flying stock market leaders and reallocating to more defensive names and asset classes.

If that sounds like catastrophising, at least rigorously stress-test your portfolio against a plausible drawdown of 30-50 per cent. Such a move would merely return the S&P 500 to its pre-2020 levels. By the way, it’s not unusual for gold to crash after steep vertical ascents.

My remaining suggestions are to eschew the herd mentality inherent in passive strategies, maintain some liquidity to exploit dislocations and prioritise active management, emphasising value, risk controls, and margins of safety, which regain efficacy when ‘themes and memes’ give way to fundamentals.

Passive investing was conceived to excise emotion. Instead, it has entrenched crowd behaviour, including madness, and inflated bubbles with mechanical indifference. For those with some experience, the underlying market fragility isn’t a hazard, but an opportunity. Be prepared to take advantage of the inevitable reversion to reality.