Australia’s gas crisis – rich in resources but struggling with energy costs

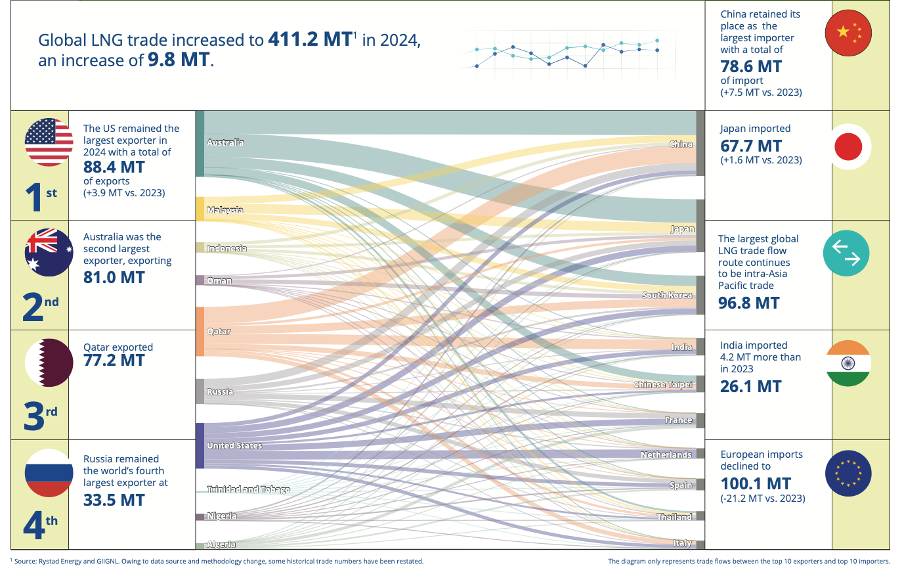

Australia is the world’s second-largest exporter of liquefied natural gas (LNG), with an output of 81 million tonnes (MT) in 2024, surpassed only by the U.S., according to the International Gas Union 2025 World LNG Report. In a year when global LNG trade expanded by 2.4 per cent to 411.24 MT, Australia contributed a 1.48 MT increase, connecting 22 exporting markets with 48 importing ones.

Figure 1. Global LNG trade

Source: International Gas Union 2025 World LNG Report.

Australia’s gas is primarily shipped to Asian markets – China, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan – often under long-term, 20-year contracts such as with INPEX (Japan’s largest oil and gas exploration and production company), that shifted to LNG after the 2011 Fukushima tsunami disaster shuttered its nuclear plants. Today, however, Japan/INPEX uses only two-thirds of the LNG its buys from Australia and Qatar, reselling the remainder for substantial profits. Bloomberg estimates Japanese companies, including INPEX, earned US$14 billion (A$27 billion) in the year ending March 2024 by arbitraging cheap contracted LNG supplied by Australia on the global market.

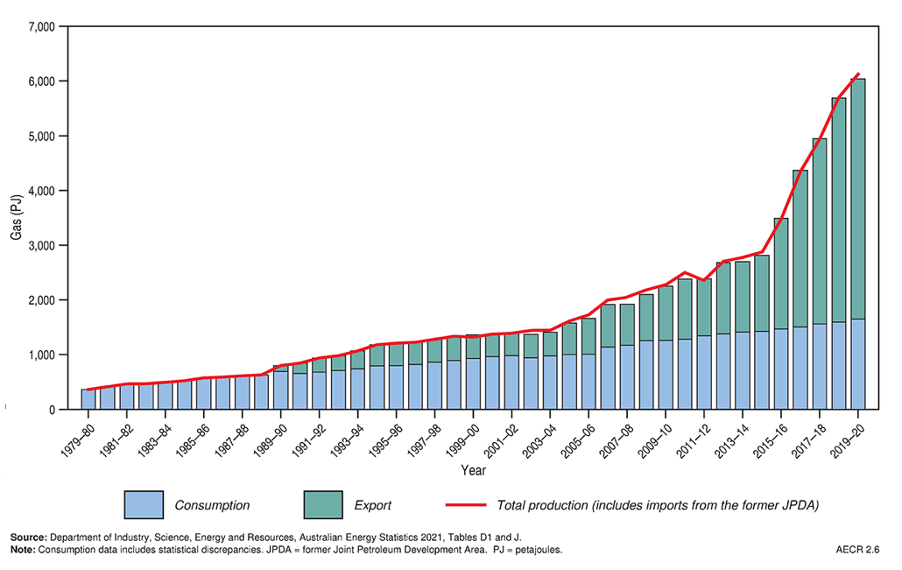

Figure 2. No gas shortage in Australia

Source: Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources, Australian Energy Statistics 2021.

Despite this abundance, Australian households and businesses face escalating energy costs, which have become a major driver of the nation’s cost-of-living pressures. Gas now generates one-third of Australia’s domestic energy needs, a significant rise from just 10 per cent in the late 1970s, as detailed in the Energy Institute – Statistical Review of World Energy 2024.

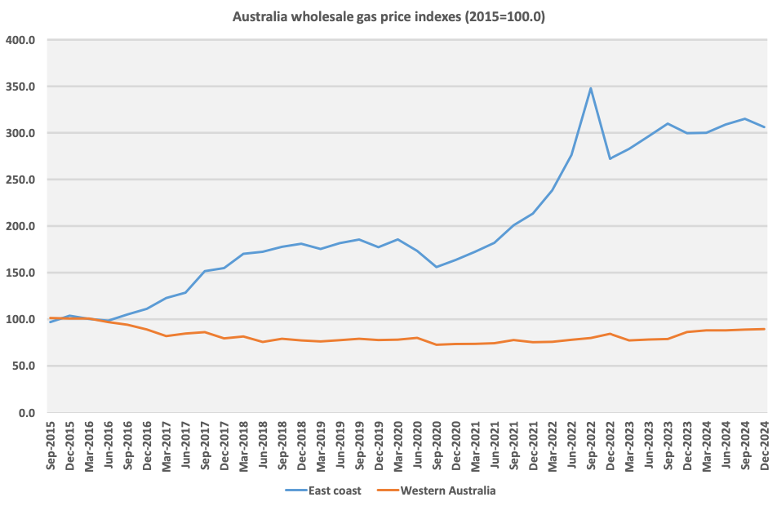

Figure 3. Australian domestic wholesale gas prices triple

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics

Yet, domestic wholesale gas prices on the east coast have tripled since 2015, and household gas bills in eastern capitals have surged by 57 per cent, compared to a modest 22 per cent increase in Perth, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics. This raises two critical questions: Why are Australians paying so much for a resource they own, and is the nation receiving fair compensation for its gas extraction?

Australia’s gas wealth and export-driven model

Australia operates ten LNG export facilities: five in Western Australia, three in Queensland, and two in the Northern Territory. These facilities underpin the nation’s status as a global LNG powerhouse. However, as Figure 2., reveals, between 75 and 80 per cent of Australia’s gas production is exported, leaving domestic markets vulnerable to shortages.

Industry voices, such as Royal Vopak, have cautioned that Australia’s era of affordable gas may be nearing its end, stating, “Australia has been very lucky because it has been living on very cheap domestic gas for a long time,” and warning, “If you don’t have the rocks, you don’t have the gas, that’s it.” Yet, this perspective reveals self-interest as it’s at odds with Australia’s vast reserves, which could supply domestic needs many times over if prioritised.

Importing gas insanity

The contracted export-heavy model has led to an extraordinary paradox: Australia, one of the world’s largest LNG exporters, may soon become an importer to meet domestic demand. The Australian Financial Review reports that LNG tankers could begin docking at Port Kembla, south of Sydney, by June 2026 to avert a projected winter gas shortage in southern states.

This absurd potential reliance on imports highlights systemic issues in how Australia manages its gas resources, particularly when global LNG prices are tied to the U.S. dollar, and a weak Australian dollar – already struggling against its U.S. counterpart –could further inflate costs for imported gas that originates from Australia’s own fields.

The east coast gas crisis: a decade of policy failures

The east coast of Australia, particularly New South Wales and Victoria, faces a looming gas shortage driven by a combination of declining legacy gas fields, long-term export commitments, and a decade of policy missteps.

Unlike Western Australia, which implemented a domestic gas reservation policy during its LNG boom to secure local supplies, the east coast operates under a complex web of federal and state regulations. These, coupled with political divisions over climate goals and public opposition to gas development, have left the region exposed to supply constraints. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) projected a gas surplus for 2025 in December 2024, but by March 2025, it warned of a worsening outlook for the third quarter, noting the market’s reliance on uncontracted LNG to avoid shortfalls.

And while the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) has delayed its shortfall forecast to 2029 under peak conditions, we are reminded, again, of the influence of self-interested operators. The trend points to tightening supplies.

Queensland’s coal seam gas, primarily extracted for LNG exports from Gladstone, is locked into long-term contracts, limiting its availability for southern states. Limited infrastructure to supply gas directly to Victoria from Queensland also presents logistical issues.

Legacy gas fields in the Gippsland, Otway, and Cooper basins are depleting, and potential new sources, such as the Narrabri gas field in New South Wales and the Beetaloo sub-Basin in the Northern Territory, are stalled by lengthy approval processes and public resistance.

It’s reported that in Victoria, approving gas projects now takes longer than building them, and approved projects often face litigation, further delaying development and inflating costs.

If the Federal government doesn’t intervene more thoughfully, these challenges have created a supply gap that may force reliance on costly LNG imports, particularly in Victoria, where import terminal development also faces delays.

Ironically, efforts to reduce gas development to accelerate the transition to renewables and cut emissions have had unintended consequences. Governments have extended the operation of high-emission coal-fired power stations to bridge the energy gap, undermining environmental objectives.

Federal interventions to date, such as a A$12/gigajoule price cap on new wholesale gas contracts and tightened export restrictions, have failed to significantly lower prices. The ACCC reports that over 90 per cent of east coast gas sales evade the cap, and the shift to shorter-term contracts has increased risks for buyers while discouraging infrastructure investment.

In contrast, Western Australia’s domestic reservation policy has kept gas prices stable, with Perth households paying far less than those of us on the east coast, especially during global market disruptions like the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Resource ownership and lost revenue

Australia’s gas resources are publicly owned, with state and territory governments managing them on behalf of citizens. The Northern Territory Government defines petroleum royalties as “payments made to the Territory as the owner of the resources,” while Western Australia views royalties as “a purchase price for the resource,” emphasising that “the community expects a fair return for the loss of its non-renewable petroleum resources.”.

In practice, however, a significant portion of Australia’s gas is exported without royalties, particularly from offshore fields in Commonwealth waters, including major projects like Chevron’s Gorgon and Wheatstone, Shell’s Prelude Floating LNG, and Woodside’s Pluto. In 2022-23, when LNG prices soared due to global energy market chaos, the industry paid just A$2.8 billion in royalties on A$71 billion in exports – a mere 3.8 per cent of the total value, according to the Australian Energy Statistics 2023.

And while these operators pay little in royalties, they appear to pay even less in tax. In fact, the Australian Taxation Office has labelled the oil and gas industry a “systemic non-payer” of tax.

In 2020-21, major LNG exporters – Woodside, Exxon, Shell, Chevron, INPEX, and APLNG – enjoyed record prices, which drove their income to A$56.3 billion. They paid just A$454 million in company tax, a rate of 0.8 per cent, thanks to tax credits accumulated under current rules.

Over the last four years, Australia’s LNG exports totalled A$265 billion, with A$149 billion royalty-free, including all LNG exports from the Northern Territory and those from four of five facilities in Western Australia. A 20 per cent royalty on these exports could have generated A$53 billion for public coffers.

International comparisons highlight the absurdity of Australia’s shortfall. Qatar, producing 50 per cent more oil and gas than Australia, generates six times more government revenue from its industry. Norway, which exports more oil and less gas, earned an estimated A$127 billion in tax revenue from its oil and gas sector in 2023 alone.

These nations utilise resource wealth to fund strong public services or sovereign wealth funds, whereas Australia’s healthcare, education, and childcare systems face significant underfunding and the country’s quality of life declines. Some estimates suggest that teachers collectively pay more in income tax than the entire gas industry, highlighting the inequity in the distribution of resource wealth.

The forgone revenue from royalty-free exports and minimal taxation could transform Australia’s public services. A sovereign wealth fund, like Norway’s, could ensure long-term prosperity, or direct investments could enhance schools, hospitals, police forces, and infrastructure, raising living standards. Instead, the current system enriches a handful of corporations and individuals while leaving consumers and small businesses to bear record-high energy costs.

Potential solutions

Addressing Australia’s gas dilemma requires reforms to prioritise domestic needs and ensure fair compensation for public resources.

One proposed solution is a WA-like national domestic gas reservation policy, as pledged by the federal opposition, which would have diverted 50–100 petajoules of gas from exports to the domestic market if implemented. Macks Advisory suggests a more comprehensive approach: a coast-to-coast 15 per cent domestic reservation policy paired with a 100 per cent tax on export sales above A$7/gigajoule. This, Macks Advisory argue, could stabilise domestic prices at A$7/gigajoule while generating A$10 billion in treasury revenue.

Western Australia’s experience demonstrates the viability of such policies. Despite initial industry objections and threats to relocate multibillion-dollar projects, Western Australia’s gas sector has thrived, and its consumers have enjoyed stable prices, even during global market shocks like the 2022 Russia-Ukraine conflict.

Others suggest another option is redirecting uncontracted LNG spot sales to the domestic market. Evidently there is sufficient uncontracted gas available to alleviate forecast shortages, and this approach could avoid disrupting long-term export contracts while addressing imminent forecast supply gaps and mitigating the need for imports.

Infrastructure investments to connect Queensland’s gas fields to NSW and Victoria could also reduce reliance on imports, offering a more sustainable alternative to spending billions on LNG import terminals.

In extreme scenarios, why not advocate for federal intervention, such as declaring a national emergency or invoking force majeure to renegotiate export contracts and rewrite industry rules. This would prioritise domestic supply and ensure operators pay a fair price for extracting resources that belong to the commonwealth (all of us). However, such measures would likely face significant industry pushback, with groups like the Australian Energy Producers arguing that policy changes could deter investment and jeopardize energy security.

Western Australia’s experience however counters this narrative, showing that balanced policies can support both industry growth and domestic needs.

A path forward

Australia’s gas wealth is a double-edged sword. As a global LNG leader, Australia could generate substantial export revenue. Instead domestic consumers face soaring energy costs, and public revenue from royalties and taxes falls far short of its potential.

A decade of policy failures, regulatory delays, and a lack of foresight has created a paradox where Australia may import its own gas to meet demand. By learning from Western Australia’s domestic reservation policy and international models like Norway and China where the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) co-owns all operators, Australia could secure affordable energy for its citizens, fund world-class public services, and manage environmental concerns.

The solutions – whether through reservation policies, redirecting spot sales, or infrastructure investments – require cooperation between state and federal governments, as well as a commitment to balancing economic, environmental, and social priorities. You would think with the ALP fronting both state and federal governments, co-operation wouldn’t be an issue.

With a thoughtful approach to its resource management, Australia could ensure that its gas wealth benefits all Australians, not just a select few corporations and individual billionaires.

Disclaimer

The Montgomery Fund, the Montgomery [Private] Fund, and Australian Eagle Equities Fund own shares in Woodside Energy Group. This article was prepared on 30 May 2025 with the information we have today, and our view may change. It does not constitute formal advice or professional investment advice. If you wish to trade Woodside Energy Group you should seek financial advice.

Great article. People underestimate what Tamboran Resources is building up their in the Beetaloo. By 2030 they will produce 2BCF of gas per day. Brokers do not follow it in Australia because they do their cap raises in the USA now. They will supply circa 30% of east coast gas requirements themselves. An upstream midstream and LNG powerhouse.

Thanks for the encouraging words Warwick and for the tip!