Are there good times ahead for the Montgomery Alpha Plus Fund?

In August 2016, we launched the newest fund in the Montgomery stable – the Montgomery Alpha Plus Fund – a “market neutral” fund designed to deliver positive returns over long time frames regardless of the overall direction of equity markets.

When we launched the fund we described in a series of articles the investment process being followed and the return profile that might be expected. These can be found here. To quickly recap, there are three key elements to building portfolios for the Alpha Fund:

- Each ASX200 company is given a quality score using our standard quality assessment framework. This framework is based on 11 building blocks of quality, which include factors like pricing power, industry structure, growth potential, stability of demand, excess return potential, etc.

- A near-term total return forecast is calculated for each ASX200 company using a machine learning system which analyses financial statements, broker forecasts and market trading data to assess value, financial strength and other metrics to distinguish stronger investment candidates from weaker ones.

- These two measures are combined to select portfolio holdings. A portfolio model assembles the most and least attractive stocks into the optimal long and short portfolios while keeping overall portfolio risk within a pre-determined level.

This process results in a long portfolio weighted to the higher-quality, financially stronger candidates, and a short portfolio weighted to the lower-quality, financially weaker candidates. The fund makes positive returns if the long portfolio performs better than the short portfolio, regardless of whether broader equity markets are rising or falling.

Eight months have now passed, and while it is early days for the Fund, we can make some observations on what has been driving the Fund’s returns during this time, and what this might mean going forward.

First of all, the performance in this early stretch is clearly not what we would have liked. When we launched the Fund, we set out here an estimate of the likely range of investment outcomes over time. We knew at outset that the Fund would experience good times and bad times, and depending on when these times came and went, the early returns could be positive or negative. With the Fund currently sitting at the bottom end of the forecast range, the early returns have clearly come from the “bad times” side of the ledger. It is natural to ask what has driven that, and when it might give way to better times.

With the fund’s portfolios selected on quality and near-term forecast return, weak results for the fund arise when one or both of these factors are moving in the wrong direction. Regular readers will know that the last 12 months in the Australian equity market has seen a strong run from lower-quality businesses, and managers who favour high-quality businesses have had a correspondingly difficult time. It seems reasonable to expect that the “quality” aspect of the Alpha Fund’s process has encountered headwinds during this time, but the question is just how strong.

The universe for the Alpha Fund is the ASX200, so one way to address this question is to consider what performance would have been achieved for a long portfolio containing only the highest-quality names in the ASX200, and a short portfolio containing only the lowest-quality names, over the corresponding period.

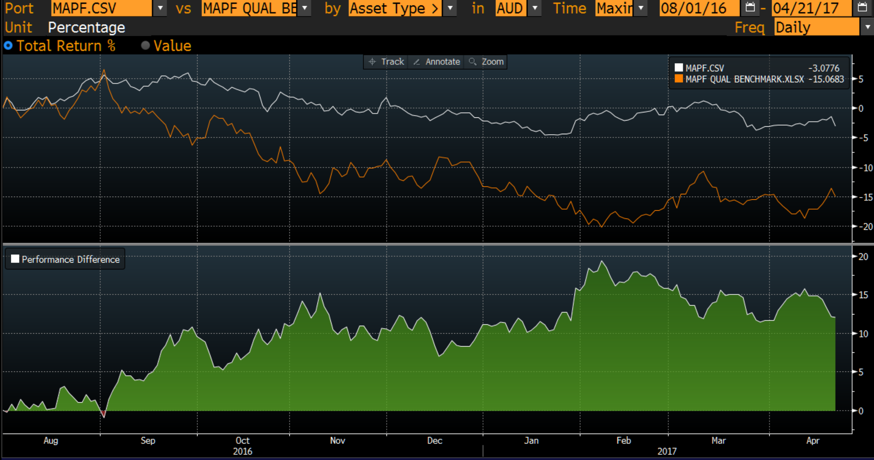

The results of this analysis[1] are set out below. What we see is that a market neutral portfolio chosen solely on the basis of business quality (as determined by our quality assessment framework) would have performed significantly worse than the Alpha Fund actually did perform. In other words, underperformance of quality (or alternatively a “junk rally”) has been a powerful force during this period. With the actual performance of the Alpha Fund significantly better than the performance of this “pure quality” benchmark, we can see that the junk rally accounts for more than 100% of the underperformance of the Fund since inception (and that other aspects of the investment process appear to have helped limit the downside and reduce portfolio volatility).

[1] Quality scores taken from MIM’s quality assessment framework as at fund inception on 1 August 2016; Benchmark long and short portfolios contain 25 equal-weighted positions; Analysis excludes transaction costs and other expenses.

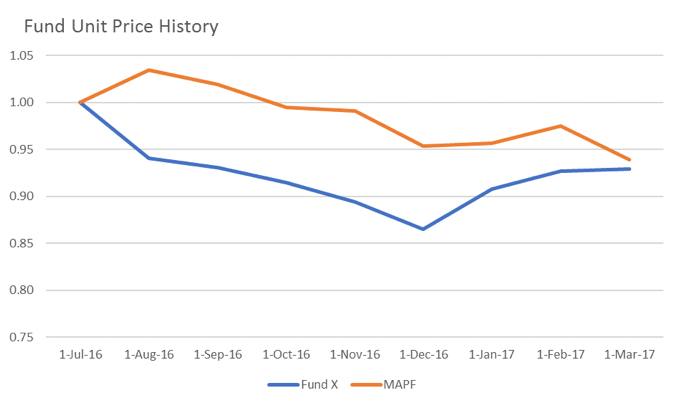

It follows that to understand whether and when the Alpha Fund will enjoy better returns, we need to understand the dynamics of investing in quality. Business quality is a cornerstone of everything we do at Montgomery, so this is a question we are happy to discuss in detail. Before we do that, however, it is relevant to observe that a number of very well-regarded Australian investment managers with strong track records have seen their relative performance suffer during this recent market phase. For interest, below we have plotted the return history for the Montgomery Alpha Plus Fund, against the return history during the same period for another market neutral fund run by one very well-regarded manager.

A little later we’ll identify Fund X and explain why it is interesting to look at this particular fund, but for now you can see that in the time the Alpha Plus fund has been running, it has delivered a similar total return to Fund X, albeit with some different ups and downs along the way. Investors in either fund would naturally be interested in whether this is an indication of the long-run performance that might be expected.

Returning to business quality, the first question is: “Why do care about it?” There are several comments worth making here:

Firstly, when we refer to quality, we are referring specifically to the ability of a business to create incremental value for its shareholders over time. This happens when $1 of extra capital invested in the business creates an earnings stream worth more than $1. A low-quality business can be thought of as a business that does the opposite – it destroys shareholder value by investing capital at a return lower than the cost of that capital.

There is an obvious intuition to this. A business that can create value over time should provide a better experience for its investors through the compounding of this value creation over the years. Conversely, a business that destroys value will need additional capital injections to replace the “lost” capital, and the long-run return to shareholders will suffer.

Secondly, there is strong academic research in support of owning quality companies. While there are many different ways to define and measure quality, the underlying concepts tend to be fairly similar – growth, profitability, consistency. A very thorough piece of research can be found in this 2013 paper by Asness et al. Among the findings in the paper:

- Higher quality companies deliver better risk-adjusted investment returns than lower-quality companies;

- This effect can be seen over long timeframes and across a wide range of countries;

- High quality businesses appear to shine especially in times of market stress, but can lag in bull markets; and

- The “price premium” the market is willing to pay for quality varies over time. Quality can underperform when the price premium declines, but this tend to precede stronger returns to quality in future.

So, quality has some strong arguments in its favour. It is of course open to investors to try to rotate in and out of high quality businesses when they believe the price of quality may rise or fall, and thereby get the best of both worlds, and some investors try to do this. We do not attempt to do that because we believe it is very hard to predict turning points in the cycle, and unless you can make these predictions reliably it is hard to justify ever owning lower quality businesses. As a result of our single-mindedness, we expect to experience times of short-term underperformance, but the compensation is a high likelihood of long-term outperformance.

This leads us to think that the recent weak performance of the Alpha fund does not demonstrate a defective investment approach, but more a consequence of its “quality at all times” philosophy. Unfortunately, we cannot forecast the timing of any change to the market dynamics. However, we are confident that over the long run, maintaining this focus on quality should deliver good results, and periods of relative weakness will typically be followed by periods of relative strength.

On the topic of long-term returns, Fund X mentioned above is the Bennelong Long Short Equity Fund[2]. While there are some significant differences in approach between this fund and the Alpha Plus fund, we chose it because it is a market neutral fund that has been running since early 2002 – some 16 years – and has been managed by one of the best-regarded investment managers in the country. As such, it provides some useful long-term perspective.

In those 16 years, the fund has been extremely successful. It has delivered a compound return of 16.4% p.a., giving the original investors 10 times their initial investment, and has delivered positive returns in 14 of the 16 years. While it is currently experiencing a significant drawdown, in the context of its exceptional history, this can be seen as an illustration that a very effective investment strategy will experience periods weakness in certain market conditions.

In conclusion, when considering the prospects for the Alpha Plus Fund, the recent performance numbers may not be the best guide. A better approach may be to consider whether the underlying philosophy and approach makes sense, and whether recent market dynamics have weakened or strengthened the case for owning high quality companies today.

[1] Quality scores taken from MIM’s quality assessment framework as at fund inception on 1 August 2016; Benchmark long and short portfolios contain 25 equal-weighted positions; Analysis excludes transaction costs and other expenses.

[2] Due to its long history of success, the Bennelong Long Short Equity Fund has reached capacity constraints and is closed to new investors.

Hi Tim, apologies for so many questions about your ML model – its truly fascinating. Would Montgomery use the output from its ML model to exclude companies or as the basis for further research in its analyst driven long only funds, including your Global Fund?

Thanks.

Kelvin

No problems, Kelvin. All the other funds, including global, use the ML model to help focus analyst research work on the most interesting targets.

That’s great, thanks Tim.

Kelvin

Thanks Tim, I appreciate your reply. As you note, others may hold the same view as myself regarding fees. I am wondering whether your total remuneration , via increased FUM, may increase if more customers were enticed to invest on the basis of a perceived “fairer” fee structure.

Anyway, in the meantime I am still an avid reader of this website and very much appreciate your insights.

Hi Tim. I was keen to invest some funds in the Alpha Fund. However, I was turned off by the fee structure.

As I understand it, you charge a fixed management fee based on FUM (fair enough) but also charge a performance fee based on outperforming the cash rate, which to me is an inappropriate and low hurdle for the risk of investing in an equities based fund.

Hi Scott. I understand your view, and you are not alone in holding it. Market neutral funds normally use a cash benchmark because they have no net exposure to the equity market, and so an equity market benchmark is inappropriate. You could argue that a hurdle higher that the cash rate would be better for unit holders, and you would be right. The logic is the same for long-only funds – if market neutral funds were required to meet a hurdle above the cash rate, then long-only funds should be required to meet a hurdle above the market rate. There is no reason that couldn’t happen, but in that case you would expect higher performance fee percentages to allow managers to retain skilled people.

Hi Tim, thanks for the response. That is really interesting.

Kelvin

Hi Tim, thanks that’s a really helpful explanation. I have two questions:

1.) Are the buy/ short sell decisions for this fund totally computer/ machine learning driven, so that there is no human or analyst intervention?

2.) If so, would it be beneficial to add an element of human common sense check, e.g. I noticed several months ago that the fund was short NST – even though it may be a low quality business, a human analyst may conclude that NST’s performance is really driven by the gold price and no one can predict that, so its just a coin-toss/ gamble and so exclude it from the portfolio?

Thanks.

Kelvin

Hi Kelvin,

There are two ways analyst intervention can shape the selections. Firstly, the quality score is analyst-driven and incorporates our judgements about future changes to industry structure, business models etc. Secondly, we can exclude individual names from selection in cases that we believe are outside the machine learning model’s normal range. For example in takeover situations, or where we think the accounting numbers may be misleading. In the case of resources companies, interestingly, we find that the ML model has pretty good forecast performance, and when we test the model on a universe with and without resources, we find that the broader opportunity set for “with” improves the overall result.

Hi Tim, just out of interest, how many years back did you test the ML model on?

Thanks.

Kelvin

Hi Kelvin,

We typically use a 10-15 year sample period to build the model. If the most recent 10 years is “normal” we might use that. If we have an odd event like the GFC in the data, we may stretch to as much as 15 years to reduce its influence. The idea is to have a long enough sample to be robust, short enough to still be “current”. Every year (at a minimum) we rebuild the model incorporating the most recent data.

Hi Tim, thanks.

I guess what I’m wondering is if your ML model included the data from 2002 to 2007 during the super major resources bull market, whether the result would still improve if it included resources companies? Thanks.

Kelvin

The nice thing about a quant model is that you can run analysis like that fairly readily. I can’t attach images to this reply, unfortunately, but will email you a chart that shows the correlation between forecast returns and actual returns for our current ML model applied to just the materials and energy sectors. You’ll see that it has fairly solid performance during the period since 2007. Note that with only two GICS sectors we have a limited number of companies, and the data gets a bit noisy in the earlier years due to diminishing sample size.