Perhaps one of the most important charts?

Late last year the Federal Bank of San Francisco’s research department published their findings about a relationship between the ageing baby boomers and P/E ratios. I have long held the view that when Australia’s baby boomers (the majority of whom are asset rich and cash poor) reach the age that they need to fund their retirement spending and healthcare, they will need to sell their assets (typically real estate). Given the next generation have long complained of being unable to afford a house, it seems logical that prices for homes will need to fall. Only if prices fall can a generation of sellers meet the generation of buyers who say they cannot afford to pay current prices.

Late last year the Federal Bank of San Francisco’s research department published their findings about a relationship between the ageing baby boomers and P/E ratios. I have long held the view that when Australia’s baby boomers (the majority of whom are asset rich and cash poor) reach the age that they need to fund their retirement spending and healthcare, they will need to sell their assets (typically real estate). Given the next generation have long complained of being unable to afford a house, it seems logical that prices for homes will need to fall. Only if prices fall can a generation of sellers meet the generation of buyers who say they cannot afford to pay current prices.

If that is indeed true for one asset classes then perhaps it makes sense for other asset classes. Wealthier baby boomers with DIY share portfolios will also need cash. They may not sell the family home (although downsizing is a very real trend), instead they may use their share portfolios as their ATM. This could put pressure on the multiples of earnings, sales and book values that trade in a free market.

The FRBSF seems to agree…Zheng Liu and Mark M. Spiegel discovered a strong relationship between the age distribution of the U.S. population and stock market performance.

“A key demographic trend is the aging of the baby boom generation. As they reach retirement age, they are likely to shift from buying stocks to selling their equity holdings to finance retirement. Statistical models suggest that this shift could be a factor holding down equity valuations over the next two decades.

The baby boom generation born between 1946 and 1964 has had a large impact on the U.S. economy and will continue to do so as baby boomers gradually phase from work into retirement over the next two decades. To finance retirement, they are likely to sell off acquired assets, especially risky equities. A looming concern is that this massive sell-off might depress equity values.

Many baby boomers have already diversified their asset portfolios in preparation for retirement. Still, it is disconcerting that the retirement of the baby boom generation, which has long been expected to place downward pressure on U.S. equity values, is beginning in earnest just as the stock market is recovering from the recent financial crisis, potentially slowing down the pace of that recovery.

We examine the extent to which the aging of the U.S. population creates headwinds for the stock market. We review statistical evidence concerning the historical relationship between U.S. demographics and equity values, and examine the implications of these demographic trends for the future path of equity values.

Demographic trends and stock prices: Theory

Since an individual’s financial needs and attitudes toward risk change over the life cycle, the aging of the baby boomers and the broader shift of age distribution in the population should have implications for capital markets (Abel 2001, 2003; Brooks 2002). Indeed, some studies attribute the sustained asset market booms in the 1980s and 1990s to the fact that baby boomers were entering their middle ages, the prime period for accumulating financial assets (Bakshi and Chen 1994).

However, several factors may mitigate the effects of this demographic shift. First, demographic trends are predictable and rational agents should anticipate the impact of these changes on asset demand. Consequently, current asset prices should reflect the anticipated effects of demographic changes. In addition, retired individuals may continue to hold equities to leave to their heirs and as a source of wealth to finance consumption in case they live longer than expected (e.g., Poterba 2001).

Foreign demand for U.S. equities might also reduce the downward pressure on asset prices. However, the effect is probably limited for two reasons. First, other developed nations have populations that are aging even more rapidly than the U.S. population (Krueger and Ludwig, 2007). Second, there is substantial evidence of home bias in equity holdings. Individual investors typically hold disproportionate shares of domestic assets in their portfolios. For example, in 2009, the foreign equity holdings of U.S. investors were only 27.2% of the share of foreign equities in global market capitalization. While the low level of international equity diversification is still not well understood (Obstfeld and Rogoff 2001), it suggests that foreign demand for U.S. equities is unlikely to offset price declines resulting from a sell-off by U.S. nationals.

Demographic trends and stock prices: Some evidence

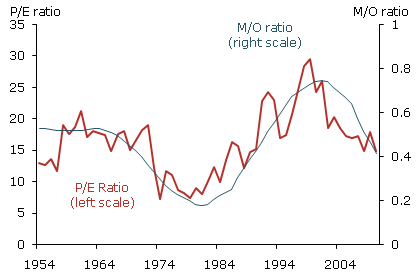

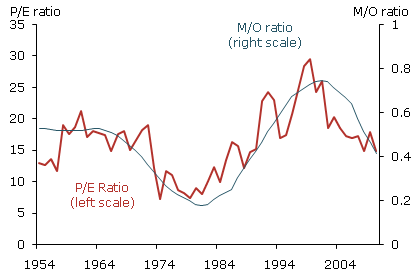

To examine the historical relationship between demographic trends and stock prices, we consider a statistical model in which the equity price/earnings (P/E) ratio depends on a measure of age distribution (for another example, see Geanakoplos et al. 2004). We construct the P/E ratio based on the year-end level of the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index adjusted for inflation and average inflation-adjusted earnings over the past 12 months. We measure age distribution using the ratio of the middle-age cohort, age 40–49, to the old-age cohort, age 60–69. We call this the M/O ratio.

We prefer our M/O ratio to the M/Y ratio of middle-age to young adults, age 20–29, studied by Geanakoplos et al. (2004). In our view, the saving and investment behavior of the old-age cohort is more relevant for asset prices than the behavior of young adults. Equity accumulation by young adults is low. To the extent they save, it is primarily for housing rather than for investment in the stock market. In contrast, individuals age 60–69 may shift their portfolios as their financial needs and attitudes toward risk change. Eligibility for Social Security pensions is also likely to play a first-order role in determining the life-cycle patterns of saving, especially for old-age individuals.

Figure 1 displays the P/E and M/O ratios from 1954 to 2010. The two series appear to be highly correlated. For example, between 1981 and 2000, as baby boomers reached their peak working and saving ages, the M/O ratio increased from about 0.18 to about 0.74. During the same period, the P/E ratio tripled from about 8 to 24. In the 2000s, as the baby boom generation started aging and the baby bust generation started to reach prime working and saving ages, the M/O and P/E ratios both declined substantially. Statistical analysis confirms this correlation. In our model, we obtain a statistically and economically significant estimate of the relationship between the P/E and M/O ratios. We estimate that the M/O ratio explains about 61% of the movements in the P/E ratio during the sample period. In other words, the M/O ratio predicts long-run trends in the P/E ratio well.

Figure 1.

This evidence suggests that U.S. equity values are closely related to the age distribution of the population.”

Posted by Roger Montgomery, Value.able author and Fund Manager, 31 January 2012.

You mention John Geanakoplos, his theory of how collateral and margins affect asset prices over the long run would also be a great addition to this discussion. For anyone whos interested Yale now offers a Geanakoplos finance theory course for free at:

http://oyc.yale.edu/economics/financial-theory/content/class-sessions

Not sure I agree with the view that BBs will simply sell down their assets.

On the property front, they (the savvy ones) will have continually acquired to ensure a negatively geared portfolio to minimise tax. Once they retire, they only need to sell a small percentage of their properties to bring the remainder into positively geared territory. Then they have the ATM of which you speak.

As for shares, income investors will have their ATM already and growth investors can either cash in (for negligible capital gains tax) or trade across to high yielding stocks.

On top of this, they’ll be feathering the nests of their Gen Y offspring with ‘off-market’ house transactions, thus excluding the masses who want to get in.

I do agree with the fundamental premise of BBs adding to stock however I think they’ll be selling some chattels rather than the whole farm.

Thanks Terry, For many BB’s, off market transfers to offspring do not provide the cash they may need.

Roger and others,

The baby boomers selling is only one side of the argument. The other side the buyers are the people just beginning to work will be buyers through their super funds, these will last for the next 45-50 years. Then anyone now between 45 and retirement will be buyers possibly big ones as most of them will only have small superfunds set aside. Also the possibility of compulsory super contributions being raised 33%. Methinks there will be plenty of buyers.

Regards Ian B

And thats why the Federal Reserve Bank of San Fran looked that the ratio of 45’ers to 69’ers. The proportion of the buyers compared to the sellers is declining. In other words there is an increasing number of sellers compared to buyers.

Welcome back Roger.

A nice little study. Have you looked at Harry Dent’s (albeit self-promotional and alarmist titled) works? I posted an (overly wordy) reply to your 2031 predictions thread on the topic I think.

Dent is another demographer who looks not just at savings patterns, but spending patterns – peak spending is around age 46-50 and in a consumer driven economy, increased spending by the boomers entering this age leads to increased earnings for businesses, and with increasing earnings comes the expectation of continued growth, thus the PE expansion.

So it’s not necessarily Boomer’s savings going into the market driving up prices (the supply-demand argument for why P in P/E should increase – which reeks of false neoclassical economics and efficient markets), but Boomer’s spending patterns driving corporate earnings (increasing E), and the expectation of continued earnings growth driving market valuations (people are willing to pay more for E if they think E will continue to grow). It takes into account the behavioral impact of changing fundamentals in such a way that ‘rational agents’ need not be induced. It’s the same behavioral bias which explains why value investing works… At least that’s my biased interpretation. In which case, expect both PE contraction and earnings (growth) reductions.

Buffett started investing in a big way around the 40s-50s, when no-one wanted to be in stocks – ‘more ideas than cash’. The nominal high of 1929 wasn’t reached until the late 50’s. It wasn’t until around 1968 when the bargains dried up and Buffett called it quits for the first time. I think demographics were a player in keeping valuations so low here too. If we are going into a structural period of 20-odd years of lower market valuations, then it could be a fantastic time to be a value investor once again!

PS – I did a similar study in 2010 looking at the All-Ords index adjusted for inflation and the annual number of births lagged by ~46 years. The correlation was quite striking, despite the birth numbers not taking into account immigration patterns – every time the births index went down, so did the market; and every time it turned back up, so too did the market (but 46 years later!). The lagged births indicator has been pointing down since 2009, but was due to bottom out around 2011-2013, with the Summer of Love kids born between 1967 and 1971 coming into peak earning/spending phase around about now though to 2016-18. I’d forgotten I’d made that prediction, and haven’t updated the figure for over a year (so disregard as market timing advice – I haven’t listened to it, so why should you?).

But for the curious: http://i.imgur.com/5As2T.jpg

All would be wise to recognize that market timing (with no regard to intrinsic value) is as good as speculating in the eyes of Graham.

Very nice Rob. Don’t lag 46 years, curves shifts left and …voila! I will include the chart in the post above.

Roger, feel free to merge this with the previous comment.

“Only if prices fall can a generation of sellers meet the generation of buyers who say they cannot afford to pay current prices”.

I would disagree that this applies to the sharemarket, because as a homeowner myself, I could take various investment angles in property.

As a share investor, no one was saying “I cannot afford to buy CSL at $100, or BHP at $50” because clearly, people still were. Even with some of the companies at that time that, in hindsight were overpriced and eventually went bust – ABC, Babcock and Brown, people were stil buying them.

I could buy a house that is already expensive because I am a “GARP” or “Growth” investor and am convinced that “this” suburn will outperform the median for the city or State.

I could be a value investor and buy it for less than I believe it is currently worth (because it is run down) and a diamond in the rough…plus give me some time and I can renovate it to increase it’s value.

With shares, if I still want exposure to that company because I think it is a good one, or perhaps a takeover target and worth much more in the future than the current price (even though expensive), I could just buy less of it, maybe 100 instead of 500.

I cannot buy half or a third of a house, it is all or nothing, and really, the dynamics of property are very different to shares (as I said earlier re: “making” capital growth through renovations, even in a flat market).

Speaking of property, I am surprised that certain “luxury goods” retailers have not gone the other way and refused to sell “online”, thus making their product ‘even more exclusive’ and that you HAVE to visit the shop for it.

I was amazed that in Melbourne, there were retailers where there were velvet ropes, lines outside and people to open the door for you to the luxury boutique. It’s the whole ‘celebrity experience’ that they are also trying to sell and the more you make it exclusive, the more people want it.

Certain technology companies don’t, or make out that certain goods are “sold out”, thus making it appear that there is a shortage (purely artificial) and fuelling demand. Great trick.

good points. Thanks Chris.

But if property where to fall in price due to M/O and thus rents went up in % terms to say 11%. Would people still be inclined to buy shares on yeilds of 2-5%. If not, then the $100 or $50 sample is irrelevant. They may be buying or not buying based on comparative returns. And thus if that did come true, prices of equities would need to drop relative to earnings to attract investors from property to equities.

I would have to disagree; you are assuming that young people have some exposure to shares (when there are options available for “just” exposure to property or even international markets, whcih move differently to ours) and there are always “100% cash” or “conservative” options which do not have any share exposure.

The most inexperienced investors, which could be argued to be young people, may have knee jerked their reaction in 2008 to the GFC, crystallising losses into cash and then said “See, I told you so” when comparing the 3-year return of “Growth” options versus fixed interest or cash to rationalise and justify their decision.

Furthermore, some people are waking up to the fact that in a falling or flat interest rate environment, their maturing term deposits are not offering anywhere near what they were when they locked them in, hence a dividend of 5-6% from a share or LIC, PLUS possible capital growth versus a lower yield and no capital growth from a term deposit seems to be a no brainer.

(To me at least).

And the baby boomers will spend less in retirement than they did when they were raising their kids, and in all probability have not accumulated enough capital to sustain their pre-retirement life styles.

Also they did not breed as well as their parents so there are less children to spend, so less consumption here as well.

Lower consumption = lower profits = loer share prices.

Hi Roger,

Love Skaffold thanks. Easy to navigate and saves an immense amount of time.

The social trend discussed in this blog piece is one which has been argued for a number of years now. It is obviously very difficult to correlate market movement with this trend so the chart presented takes a pretty good shot at it.

What I am more interested in is identifying which industries would benefit from this shift of money. If they are cashing in for lifestyle funding reasons then there will be companies waiting to benefit from this (e.g. Fleetwood). If they are merely cashing in to beef up liquidity there will be benefactors from the providers of products in this market (the banks for starters).

Similar to what we are witnessing with retailing, as trends shift, new players emerge to benefit from the change leaving the turnaround optimists treading water in their wake.

Thanks Graham,

The healthcare theme seems an obvious one too.

SOL they will all need frequent supplies from chemists

Hi Roger,

An interesting article. An equivalent graph for the Australian stock market would also be fascinating.

The potential offset in the Australian market is the growing compulsory superannuation contributions which come out of most pay packets week in and week out, and which does see most of the younger demographic purchase shares (whether they know it or not).

Even with the correlation between our market and the US market, this factor may reduce the head winds from the sell-down of retirees assets for us to some extent at least (although I’m only speculating).

Pete

Good point Pete. I have however always been wary of the weight-of-money argument because it hasn’t prevented major sell offs in the past.

Hi Roger,

In a sense, this graph presents the ‘weight-of-money’ argument in reverse (ie the weight of money is leaving the market).

Given the ‘weight-of-money’ from super didn’t really hold, that leads me to think that this might not hold either.

If so, I’ll revert to the Graham argument, which is that the market is a weighing machine and will revert to value over time. My SMSF has the luxury of time, so if there are temporary drops due to large volumes of money leaving the market at once, it may present future opportunity.

Spot on Pete.

ANother contributor offered the following:

“the research around demographics suffers from the following

1) multiple comparisons ( the base line data for M/O ratio calculation) of the same set of data

2) demographic estimates are released in July, thus the demographic data has a six month lag

3) Annual estimates of census age demographics are as-revised rather than as-released

4) there may be a data snooping bias while defining M/O ratio, why 40-49 / 60-69 band , why not some other age group”

In response to (4) above I would suggest the reason is that the 40-49 group are large wealth accumulators and in peak earnings (therefore buyers of shares) while the 60-69 group are natural share sellers. I am not concerned about six month lags as the general relationship observed is over a very long time. Its not a market timing device.